BlackWallStreet.org has found that the Origins of the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Early Economics in Relation to the State of the Republic of Texas. The institution of slavery did not begin in Texas, but Texas quickly became a vital cog in the larger machinery of the transatlantic slave trade and its economic afterlife.

To understand how deeply slavery became embedded in the fabric of the Republic of Texas and later the State of Texas, one must return to the early 15th and 16th centuries when Portuguese and Spanish maritime powers began forcibly removing Africans from their homeland.

These Africans were not nameless laborers—they were kings, farmers, midwives, blacksmiths, and griots. They were human souls reduced to chattel in the eyes of European commerce. The transatlantic slave trade soon created a triangular web of commerce between Africa, Europe, and the Americas. This triangle was not merely geographic—it represented an entire civilization’s betrayal of morality in exchange for profit. Africans were captured, sold, branded, packed into ships like cargo, and sent across the Atlantic to feed the European hunger for sugar, cotton, and labor.

This triangular trade route was reinforced by both European monarchies and rising mercantile elites. Slavery’s economics were brutal and efficient: goods such as rum, firearms, and cloth were traded in West Africa for human lives, those lives were then sent to the Americas, and the products of their labor—sugar, tobacco, indigo, and eventually cotton—were shipped to Europe. The transatlantic slave trade lasted from the early 1500s until the mid-1800s and moved over 12 million Africans across the sea. Of those, millions died in the Middle Passage or within a year of arrival. The ones who survived were sold, whipped, worked to death, or bred for further labor. It was not only a tragedy of human suffering but an engineered, state-sponsored economic system built upon bodies and silence.

Texas, originally part of New Spain, was somewhat late to adopt African slavery as a major economic engine. The Spanish Crown officially permitted slavery, but in Texas, the use of enslaved labor remained limited during most of the colonial period. Spanish settlers in Texas relied more on forced Indigenous labor and mission systems. However, once Texas came under Mexican rule in 1821 following the country’s independence from Spain, a contradiction emerged. Mexico abolished slavery in 1829 under President Vicente Guerrero, a man of African descent himself.

But in Texas, Anglo settlers from the U.S.—many of them from the South—brought enslaved Black people with them and demanded exemptions from anti-slavery laws. The friction was immediate and intense. These settlers believed slavery was essential to cultivating cotton and building personal fortunes. For them, the right to own slaves was inseparable from their vision of prosperity and identity. It would become a central cause of Texas’s eventual secession from Mexico.

After decades of Mexican attempts to restrict slavery in Texas and Anglo resistance to those policies, tensions exploded into rebellion. The Texas Revolution (1835–1836) was fought not only over autonomy and self-governance but explicitly over the right to maintain and expand slavery. When Texas declared independence and formed the Republic of Texas in 1836, it became a haven for slaveholders. The new Republic immediately legalized slavery, writing protections for slaveowners into its Constitution. Slavery was now enshrined in law and celebrated as central to the identity of Texas as a republic.

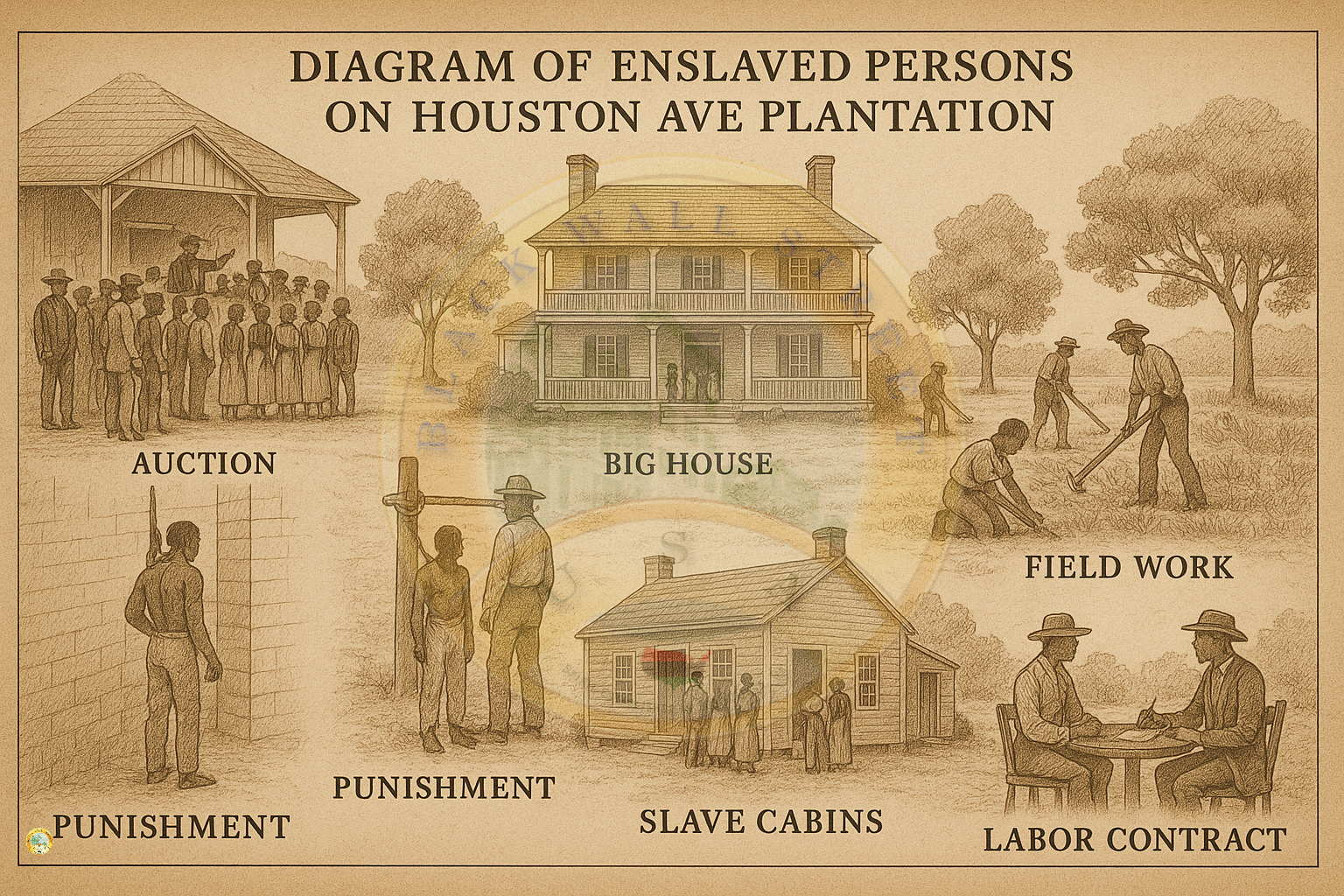

At this point, the slave economy in Texas began to align with that of the larger American South. Cotton became king. The black soil of East Texas proved ideal for its cultivation, and enslaved labor was the only engine used to extract wealth from that land. Sugar plantations in the coastal plains also became profitable, and rice-growing operations in Texas mimicked those in Louisiana and South Carolina. Enslaved Africans and African Americans in Texas labored in fields, dug irrigation channels, cleared forests, built houses, tended livestock, and raised the white wealth of the new republic. Their value was in their production, their reproduction, and their submission.

Texas was not only a participant in slavery but an expansionist force. The Republic of Texas promoted migration by offering settlers large land grants with the promise that slavery would be protected. The labor of the enslaved made the land profitable, and the profits drew more settlers, creating a feedback loop. In many ways, Texas served as a pressure valve for the overcrowded slave economies of older Southern states. When soils were exhausted or enslaved labor became politically precarious in other regions, Texas offered open land and legal protection for the slaveholder's enterprise. Between 1836 and 1845, the enslaved population in Texas grew rapidly, and by the time of statehood, over 30,000 enslaved people lived within Texas’s borders.

The Republic of Texas, then, must be understood as a state built for the preservation of slavery. It was defended militarily and diplomatically on that foundation. Its courts, schools, and land distribution systems were structured around white supremacy. The presence of slavery influenced every aspect of governance and culture. Even those who did not own slaves benefited from the system, through rents, trade, and social elevation. Poor whites gained psychological wages from the knowledge that no matter how poor they were, they were not Black, they were not enslaved, and they were not at the bottom.

It is clear that Texas was not simply influenced by slavery—it was birthed by it. From its secession from Mexico to the building of its economic structure and population policy, slavery was the bloodstream of the Republic. The enslaved were the forced architects of its towns, the silent backbone of its agriculture, and the uncredited co-authors of its wealth. The story of Texas begins in the cotton fields, sugar cane rows, and the auctions of Black bodies. That legacy did not end with emancipation. It merely changed costume.

When Texas became a U.S. state in 1845, it did not join the Union as a neutral territory. It was a slaveholding society entering an alliance with other slaveholding states, seeking greater security for its institution and economic ambitions. The annexation of Texas was not only a political transaction; it was a reinforcement of the slave economy on a national scale. The powerful Southern slaveholding class viewed Texas as their last great frontier—an expanse of land rich in soil and ripe for the expansion of a cotton empire built on the backs of enslaved labor. It was also seen as a strategic asset in preserving the balance of power between free and slave states, and ultimately as a wedge that would press the nation toward civil war.

The transformation of the Texas slave system into a fully integrated slavery industrial complex was rapid and brutal. As the cotton economy of the South intensified in the 1840s and 1850s, Texas became the hinterland for exhausted plantations in Mississippi, Georgia, and the Carolinas. The transportation networks that began to form—wagon trails, steamboat routes, and early rail lines—were engineered not merely for passenger or general freight travel, but explicitly to transport cotton and, indirectly, enslaved people.

The reach of slavery extended far beyond the plantation, linking financiers, insurers, shipbuilders, textile manufacturers, railroad tycoons, and speculators from the North and across the Atlantic. Thus, the slavery industrial complex was not limited to the Southern landowners who held whips; it also included the Boston banker who underwrote a plantation mortgage, the British textile merchant who relied on raw Southern cotton, and the insurance company in New York that profited from policies taken out on enslaved lives.

During this period, the enslaved population of Texas continued to explode. By 1860, nearly 183,000 enslaved people lived in Texas—more than 30% of the state’s population. Texas had more enslaved people than any other state in the West, and it had become a place where slavery was intensifying rather than retracting. Because of Texas’s relative geographic distance from Northern abolitionist pressure and its deep economic ties to the Confederacy, enslavers in Texas felt emboldened to continue expanding slavery up to the Civil War. Texas newspapers of the era openly printed advertisements for enslaved workers—men for field work, women for house service, children for “training.” These notices reduced human beings to commodities, and their frequency and tone spoke to a society that saw no contradiction between Christian morality and human ownership.

The slave economy had also become highly stratified. Wealthy slaveowners with hundreds of enslaved people used overseers, mid-level managers, and even corporate agents to monitor plantations. Middle-class whites could invest in partial ownership or speculate on the trade of enslaved people. Urban slavery grew, too. In towns like Houston and Galveston, enslaved men were hired out as blacksmiths, carpenters, or dockworkers. Enslaved women cooked, cleaned, raised white children, and lived under the constant threat of sale or assault. Texas’s enslaved population was highly diverse—some were born in Africa, others were second or third-generation in America. Many developed unique dialects, spiritual practices, and kinship systems to preserve their humanity and resist psychological domination.

Despite the dehumanizing system imposed upon them, enslaved people resisted in both direct and subtle ways. There were escapes, some successful, especially toward Mexico where slavery had long been abolished. Texas had a unique borderland status—those who could flee south of the Rio Grande might find freedom, and there were networks, however fragile, that aided such efforts.

Others resisted through work slowdowns, sabotage, feigned illness, or by maintaining cultural memory through music, prayer, storytelling, and naming. Family bonds were fiercely protected despite the ever-present threat of separation. Slave marriages, though not legally recognized, were sacred in their own right. Enslaved people created and protected what space they could to raise children, love one another, and assert their existence as human beings.

With the rising tensions between North and South in the 1850s, Texas doubled down on its commitment to slavery. Secessionists in the state pushed propaganda that without slavery, Texas would collapse into poverty. Cotton was not just a crop—it was currency. Politicians in Austin, many of them slaveowners themselves, declared that slavery was a positive good. Texas joined the Confederacy in 1861 with full knowledge that it was fighting to preserve slavery. The state provided troops, supplies, and strategic depth to the Confederate war effort. Enslaved people were forced to build forts, grow food for soldiers, and serve Confederate officers. They were spies, too—passing intelligence to Union forces when they could. They risked their lives to sabotage the war machine of their captors.

As the Civil War raged across the South, Texas remained relatively untouched by large-scale battles. That geographical distance meant Texas became a refuge for fleeing Confederate loyalists—and their enslaved people. Tens of thousands of enslaved people were forcibly marched into Texas from other Southern states as their white owners sought to escape Union troops. These forced migrations mirrored the domestic slave trade decades earlier and brought enormous suffering. Families were ripped apart again, and the labor demands on enslaved people in Texas increased. The state became the final stronghold of the slave power.

This map displays the routes taken by Confederate planters and their enslaved workers as they fled from Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana into Texas between 1863 and 1865. Arrows track westward movement with annotations showing key waypoints and estimated numbers. Color-coded regions show Union-occupied zones versus Confederate-controlled zones. This visualization reveals how Texas functioned as a final bastion for slavery during the war.

One of the most brutal ironies of this era was that emancipation came last to Texas. While President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, it had no practical effect in Texas due to the absence of Union troops. Enslavers ignored it and continued to profit from unpaid labor. It was not until June 19, 1865—two months after the Civil War ended—that Union General Gordon Granger arrived in Galveston and issued General Order No. 3, declaring all enslaved people in Texas free. That day, now known as Juneteenth, marked a symbolic end to slavery in Texas, but not to the structures that it created. The same white elites who had held people in bondage quickly transitioned into politics, business, and law enforcement roles, reinforcing new systems of racial control.

A linear timeline from 1836 to 1865, with key events: Texas independence, annexation, growth in enslaved population, Civil War entry, forced migrations, and finally Juneteenth. Each point on the timeline includes illustrations—chains, cotton bales, wagons, flags—to give visual emphasis to the evolution of Texas’s slavery system. This timeline helps reinforce the continuity of oppression and the delayed recognition of freedom in the state.

The Civil War did not end the slavery industrial complex. It merely forced its evolution. Former enslavers were compensated through political power and economic restructuring. Sharecropping replaced outright slavery, and laws were passed to criminalize Black freedom. Black Codes were implemented to restrict movement, labor rights, and civil participation. Prisons filled with Black men charged with “vagrancy” and “idleness,” and these men were then leased to work on farms, railroads, and in mines under conditions that in many ways mirrored slavery.

In the corporate boardrooms and financial districts of the North, there was little reckoning. The cotton grown in Texas by enslaved hands had long since been turned into wealth, passed down in the form of family fortunes, endowments, and capital investments. Insurance companies that had underwritten slave ships remained powerful. Textile companies that had relied on slave-picked cotton continued producing goods. Railroads built with slave-leased labor expanded into new markets. The names of these companies were not erased by abolition—they were sanitized, reframed, and celebrated as engines of American growth. But buried deep in the foundations of their success were bones and blood.

The end of formal slavery in Texas on June 19, 1865, did not bring with it true liberation. What followed was a devastating transformation—a legal, economic, and cultural recalibration of white supremacy. Slavery was outlawed, but white Texans sought immediately to reconstitute its power through new laws, new labor systems, and a virulent racial ideology designed to stifle Black mobility, autonomy, and citizenship. The aftermath of Juneteenth was not a season of repair but a crucible in which new methods of bondage were forged, and the early roots of what would later become the carceral state and Jim Crow Texas took hold.

Within weeks of emancipation, thousands of formerly enslaved men and women found themselves caught between a dream and a noose. With no compensation for generations of unpaid labor, no restitution, and no land, most Black Texans had little recourse but to remain near the plantations that once enslaved them. Sharecropping and tenant farming became the most common employment available. In theory, sharecropping was a contract between free labor and landowners.

In practice, it was a system of debt servitude where formerly enslaved people leased land, tools, and seed from former slaveholders, only to end each season deeper in debt than they began. The new “freedom” was riddled with contracts that were impossible to honor, bound by violence and threats of eviction, and reinforced by a racist legal system that always favored white landowners.

Parallel to sharecropping was the rise of convict leasing—a more formal resurrection of slavery under the mask of justice. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, outlawed slavery “except as punishment for a crime.” This exception clause was weaponized across the South, and Texas was no exception. Black people were arrested en masse for minor or fabricated offenses—loitering, vagrancy, unpaid fines, “disrespect.” The prison population in Texas skyrocketed, and nearly all of those incarcerated were Black men. These prisoners were leased out to private companies, railroads, and plantation owners, forced to labor under the watch of armed guards, often in worse conditions than before emancipation. The prison farms of Texas became slaughterhouses of human dignity.

From the 1870s to the early 1900s, the convict leasing system became one of the most profitable state-run industries in Texas. Inmates worked the sugarcane fields of Brazoria County, laid railroad track, built levees, and harvested lumber. Corporations paid the state for access to these prisoners—paying far less than free labor would cost—and faced no consequences for their abuse or deaths. Prisoners were whipped, shackled, starved, and left to die. There was no incentive to preserve their lives. The Texas Department of Corrections became a cartel of human rental services, with profits reinvested into the state budget.

The codification of white supremacy continued with the passage of Black Codes, which evolved into a full-fledged Jim Crow legal regime by the end of the 19th century. These laws regulated where Black Texans could live, work, gather, or attend school. Interracial marriage was criminalized. Public spaces were segregated. Voting was suppressed through poll taxes, literacy tests, and violence. The rise of lynchings as a tool of racial terror—often conducted in broad daylight with community spectators—created a climate of constant fear. From 1880 to 1930, Texas recorded hundreds of lynchings, most of which were never prosecuted. Law enforcement officers, judges, and politicians often condoned or participated in the killings.

Despite this repression, Black Texans refused to be broken. In this crucible of terror, they forged resistance movements, civic institutions, and a cultural identity rooted in dignity and determination. Churches became sanctuaries and schools of resistance. The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) and Baptist churches were particularly instrumental in organizing communities. Freedmen’s towns—such as Independence Heights near Houston and Clarksville in Austin—sprouted across the state, offering self-governed Black spaces. These were not merely neighborhoods; they were acts of rebellion, where Black Texans built homes, businesses, schools, and lives in defiance of a society determined to erase them.

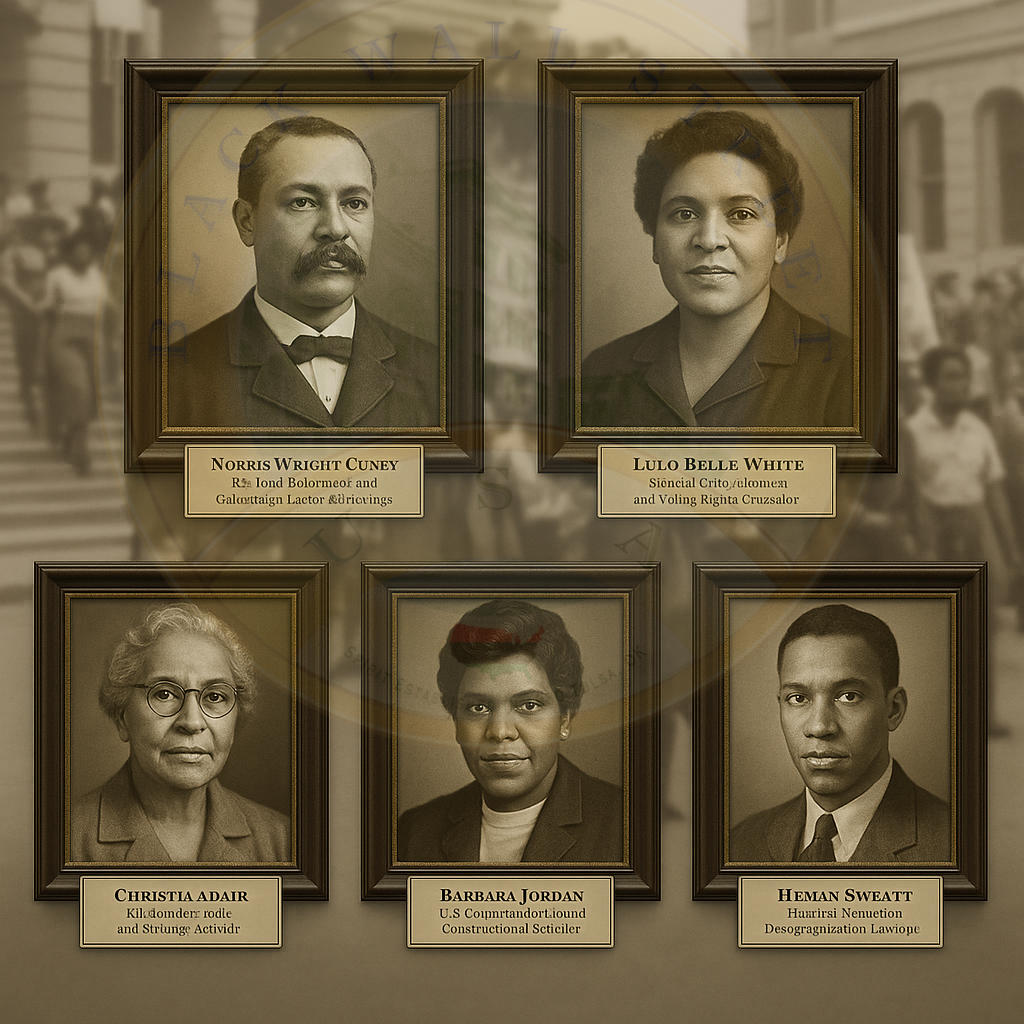

Notable Black abolitionists and civil rights pioneers emerged from Texas during this era. Norris Wright Cuney, born in 1846 in Galveston, was the son of a white planter and an enslaved woman. After emancipation, Cuney became one of Texas’s most influential Black politicians and activists. He led the Black delegation of the Republican Party in Texas and worked to secure jobs for Black workers on the Galveston docks, resisting segregation and discrimination through unionization and political strategy.

Another towering figure was Lulu Belle White, born in 1900 in Elmo, Texas. She led the Texas chapter of the NAACP during the 1930s and 1940s and was one of the first Black women in the nation to direct a statewide political movement. She fought tirelessly for voting rights, equal education, and against Jim Crow. Under her leadership, the NAACP in Texas doubled in size. She was often the only woman in rooms dominated by men and white hostility, yet her voice thundered with clarity and purpose.

The economic legacies of slavery and racism were not confined to plantations or prisons. Northern and international corporations continued to profit from Texas’s racial subjugation well into the 20th century. Railroad companies such as Southern Pacific and the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad benefited directly from convict labor. Insurance companies that once underwrote slave lives now provided policies to companies who exploited Black tenant labor. Banks, especially those in Houston and Dallas, provided capital for white agribusiness and denied loans to Black farmers. Many of the institutions that grew wealthy off cotton and sugar transitioned smoothly into oil, real estate, and industrial sectors—with profits built on historic racial exploitation.

Resistance continued. The 20th century saw the rise of a new generation of Texas freedom fighters. Barbara Jordan, born in Houston in 1936, became the first Black woman from the South elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She used her position to demand civil rights, economic justice, and the dignity of all Americans. Jordan’s voice was a thunderclap in halls long deaf to the cries of Black Texans. Heman Sweatt, in 1946, challenged the racist admissions policy of the University of Texas Law School, leading to the landmark Supreme Court case Sweatt v. Painter (1950), which helped lay the groundwork for Brown v. Board of Education.

Civil rights movements in Texas grew in power during the 1950s and 1960s. Black teachers, preachers, students, and veterans led protests, filed lawsuits, and risked their lives. Sit-ins in Dallas, marches in Houston, boycotts in San Antonio—these were not isolated events. They were part of a coordinated resistance stretching back to the earliest moments of Black life in Texas. Every prayer meeting, every community newspaper, every neighborhood school was a seed of rebellion.

Even in the 21st century, the struggle continues. Corporations and governments that benefited from slavery and segregation have been slow to acknowledge or repair the damage. The names of plantations now decorate luxury subdivisions. The descendants of enslaved Texans continue to face disparities in wealth, education, health, and justice. Yet the story of Black Texas is not only one of suffering—it is one of genius, courage, resistance, and vision. From the cotton rows of Brazoria to the halls of Congress, Black Texans have never stopped fighting.

In the years following the official abolition of slavery and the dismantling of Jim Crow legislation, Texas remained—like much of the United States—entangled in the legacies of its past. The slavery industrial complex, though stripped of its original language, never disappeared. Instead, it reconfigured itself within institutions of law, commerce, real estate, finance, and the carceral system. The modern economy and social structure of Texas carry the genetic memory of slavery in every law enforcement district, in every prison, in every urban zoning code, and in every wealth disparity across racial lines.

This labor is not symbolic—it is measurable and profitable. Inmates in Texas produce over $70 million in agricultural goods annually. They also manufacture license plates, clothing, furniture, and military gear. Corporations have historically contracted prison labor for tasks ranging from telemarketing to chemical packaging. This system not only creates state revenue and reduces operational costs—it depresses wages across entire sectors, creating an underclass of exploited workers that disproportionately affects communities of color.

The modern real estate and financial industries in Texas are also steeped in the legacy of racial exclusion. The racial wealth gap in cities like Houston, Dallas, and Austin did not emerge by chance. It was manufactured through redlining, racially restrictive covenants, eminent domain abuse, and discriminatory lending practices. Neighborhoods like Freedmen’s Town in Houston and Black East Austin were once vibrant, self-sustaining Black communities formed by the descendants of enslaved people. Today, they are shadows—bulldozed, gentrified, and rezoned for white affluence. Black families who once held intergenerational wealth in property were systematically pushed out by banks, developers, and city councils.

Simultaneously, corporations that once profited directly from slavery or from post-slavery exploitation still operate with impunity today. Insurance companies like Aetna, banks like JPMorgan Chase, and railroads like Union Pacific—all with direct or indirect ties to Texas slavery or convict leasing—continue to serve as financial giants. These corporations have often acknowledged their past with bland statements but have offered no substantial reparations. Their wealth was accumulated, compounded, and shielded across centuries, even as the communities that built them with forced labor were excluded from economic participation.

But history does not go unchallenged. In recent decades, grassroots movements for justice, accountability, and reparations have risen with clarity and force. One of the most vital embodiments of this energy is the modern Black Wall Street USA movement, which seeks to rebuild the economic and cultural power of Black communities—especially in historically traumatized regions like Texas. Inspired by the legacy of the original Greenwood District in Tulsa, Oklahoma—a thriving Black economic hub destroyed by white mobs in 1921—Black Wall Street USA is not just a name, but a declaration of survival, revival, and sovereignty.

This modern movement in Texas channels the ancestral energy of freedmen and freedom fighters. Its objectives are expansive: building cooperative Black-owned businesses, supporting youth entrepreneurship, advocating for reparations, preserving historic Black towns and churches, providing educational programs, and erecting a new economic architecture not dependent on white gatekeeping or validation. Black Wall Street USA uses both digital platforms and physical organizing to unite individuals across geography, class, and age. It has inspired the founding of Black-owned banks, fintech startups, agricultural cooperatives, and real estate collectives in Texas. The movement recognizes that economic justice is inseparable from cultural autonomy and historical truth.

The movement also embodies the moral dimension of remembrance. Juneteenth, which began in Texas as an act of communal memory, has grown into a national holiday. But in Texas, its spiritual weight remains unmatched. The descendants of those who heard General Granger’s Order No. 3 in 1865 now stand as the architects of a renewed fight—not just for symbolic recognition, but for reparative justice. They march not only with signs but with economic plans. They rally not only for apologies, but for institutional restitution. Black Wall Street USA’s alignment with Juneteenth reclaims the day from passive celebration and embeds it with political demand.

There is also a strong push to hold corporations accountable. Researchers and activists have begun compiling databases tracing modern corporate wealth back to slavery and convict leasing in Texas. Legal scholars are proposing frameworks for corporate reparations—ranging from community investment funds and scholarships to direct restitution for specific communities destroyed by racial capitalism. Churches and universities, too, are being called to acknowledge and repair their involvement in slavery. These efforts are fueled not by revenge, but by truth, equity, and a vision of collective repair.

The remembrance of Texas’s slavery history is not just academic. It is spiritual. Projects like the Texas Freedom Colonies Project, led by scholars and descendants, seek to document and protect the remaining Black settlements established after emancipation. Oral histories are being recorded. Cemeteries are being restored. Road markers are being placed where the state once erased history with concrete and silence. Each act of remembrance is a nail in the coffin of historical amnesia.

Yet challenges remain. Modern voter suppression laws in Texas disproportionately affect Black voters. The state’s refusal to expand Medicaid leaves many Black Texans without healthcare. Police brutality continues. Schools in predominantly Black neighborhoods are underfunded, and economic inequality remains entrenched. But in every field of struggle—education, housing, health, finance, agriculture, media—there are Black Texans pushing forward, invoking ancestors and inventing futures. They are the spiritual grandchildren of enslaved revolutionaries. They speak in the language of freedom, encoded not just in protest chants but in business plans, cultural celebrations, and blockchain code.

The slavery industrial complex in Texas did not end. It evolved. But so did resistance. The people who were once stripped of humanity have produced poets, presidents, professors, and prophets. Their descendants are not waiting for salvation—they are building it. Through movements like Black Wall Street USA, they are erecting systems that do not merely challenge white supremacy but replace it with Black sovereignty. They do not ask for a seat at the table—they are building their own.

As we close this act, we do not end a story—we amplify a movement. Texas was once the western frontier of American slavery. Today, it may well be the epicenter of Black economic, cultural, and political revival. Juneteenth is not an end point. It is a portal. And through it, the spirit of a people who were never meant to survive are now thriving. In their hands, the legacy of Texas slavery is being transformed—through truth, through justice, and through vision—into a future that redeems the past not through forgetting, but by demanding, remembering, and rebuilding.

The long shadow of slavery continues to cast itself over the fields of Texas—not just physically where cotton once grew and blood once fell, but emotionally, institutionally, and spiritually. From Waller County to East Austin, from Houston’s Third Ward to the Panhandle, the residue of bondage remains embedded in systems that shape public education, cultural recognition, and political representation. Yet even as these institutions reflect centuries of exclusion, a countercurrent surges through the veins of the state—an unceasing, unyielding spirit of Black liberation that continues to reassert its presence.

Public education in Texas remains a contested battlefield in the struggle over slavery’s legacy. In one of the most populous and diverse states in America, textbooks still attempt to soften or obscure the history of slavery, sometimes referring to enslaved people as “immigrant workers” or “servants.” Curriculum boards stacked with political appointees have sought to whitewash the role of slavery in Texas’s founding and the Civil War. There have been concerted efforts to block the teaching of critical race theory, an academic framework used to examine how systemic racism influences law and society. These actions amount to a second erasure—first the bodies, now the truth.

In districts serving primarily Black and Latino students, schools remain underfunded, overcrowded, and structurally neglected. Buildings crumble while wealthy suburban campuses flourish. Black students are disproportionately disciplined, suspended, and funneled into the juvenile justice system. The school-to-prison pipeline, a modern corollary to the plantation-to-penitentiary pathway, remains intact. Yet in this context of inequity, Black educators, parents, and students wage a quiet revolution. They teach the history that schools refuse to print.

They build supplemental programs, community-led tutoring initiatives, and Afrocentric curricula to ensure their children inherit not silence but strength. These educational warriors are teachers by trade and by necessity—grandparents, community activists, church leaders—ensuring that young Black Texans understand their true history, not the censored version offered by institutional textbooks. In some cases, entire schools—such as historically Black charter academies or programs within churches and community centers—have been established to cultivate a holistic education rooted in self-knowledge, collective history, and civic empowerment.

In culture, Texas has emerged not only as a site of oppression but as a stage of Black brilliance. From the spirituals sung by the enslaved in the Brazoria cane fields to the blues birthed in East Texas towns, Black Texans have used music, art, and storytelling as vessels of liberation. The Harlem Renaissance had its parallel in Texas’s own cultural explosion during the 20th century, when poets, painters, and performers challenged the mythologies of white supremacy. Today, artists like Beyoncé, born in Houston, carry the ancestral memory of this cultural resistance into global arenas. Her 2019 Homecoming performance, rich with HBCU references, Southern Black cultural motifs, and tributes to historically excluded ancestors, is part of a long lineage of Texas-born artistic liberation.

Museums, murals, poetry readings, and Juneteenth celebrations have all become battlegrounds and altars of remembrance. In towns like Galveston, where emancipation was declared, Juneteenth is not merely a festival—it is a reckoning, a sermon, a renewal. Black artists and historians, some descended from the very people who were emancipated that day, have reclaimed Juneteenth as a day of reflection and protest, joy and justice. They bring drummers and dancers, scholars and elders, children and clergy together in sacred procession. Each float, each chant, each libation poured onto the soil is a declaration: we remember, and we remain.

In modern Texas politics, the legacy of slavery is not merely debated—it is defended or defied, depending on who holds the microphone. Voter suppression remains rampant in the state. Voter ID laws, roll purging, gerrymandering, and restrictions on early voting and mail-in ballots disproportionately impact Black voters. Election districts in places like Harris County are surgically drawn to dilute Black political power. Yet in the face of such repression, Black political mobilization has not waned—it has sharpened.

Organizations such as Black Voters Matter, NAACP Texas, the Texas Organizing Project, and the League of Young Voters have formed coalitions to challenge voter suppression and increase civic participation. Black women, in particular, have emerged as the strategic backbone of Texas's progressive movements. They organize campaigns, run for office, lead protests, and draft policy. Their activism is a direct inheritance of foremothers like Lulu Belle White, Barbara Jordan, and Christia Adair.

Texas’s Black politicians today operate in the dual consciousness of knowing the system was built to exclude them and yet fighting to change it from within. Their presence in city councils, school boards, court benches, and congressional offices is not the fulfillment of a dream, but rather a demand for equity carved into the architecture of power. They legislate with the wisdom of field laborers in their bloodline and the fire of activists in their hearts.

Juneteenth, perhaps more than any other commemorative event, serves as the symbolic convergence point of Texas’s long journey from bondage to resistance. What began as a spontaneous celebration among the newly freed has become a state holiday, and then a national one, not because time healed wounds, but because generations of Black Texans insisted that forgetting was not an option. The federal recognition of Juneteenth in 2021 marked a milestone in national consciousness, but in Texas, the day remains intensely personal. It is not merely about emancipation—it is about the endurance of truth, the reclamation of history, and the refusal to allow trauma to silence tradition.

Juneteenth is a ritual of survival. It is as much about food, music, dance, and reunion as it is about reflection, mourning, and resolve. At its heart, it is a form of cultural defiance. It asserts that Black people are not simply the victims of slavery—they are the architects of a free future. It also forces a nation still allergic to truth to reckon with what freedom means and who has been denied its full measure.

As the sun sets over Texas’s sprawling plains, the legacy of slavery cannot be unseen, nor can it be undone. But what can be done—and what is being done—is the conscious, deliberate construction of a world not based on exploitation, but on restoration. Reparations efforts in Texas have gained traction. Advocates propose housing assistance, education grants, land redistribution, community funds, and apologies backed by action.

The concept of reparations is no longer whispered in activist circles; it is proclaimed on city council floors and courtroom steps. Cities like Dallas and Austin are being challenged to reconcile their wealth with the communities they displaced. Universities are being asked to return stolen history, name buildings for Black founders, and invest in the communities whose backs built their endowments.

BlackWallStreet.org, along with dozens of community coalitions, continues to ignite this fire of accountability. Their energy is not born of hate, but of clarity. They do not seek to burn America down—they seek to rebuild it on a foundation not of stolen bricks but of shared dignity. They harness the tools of today—technology, finance, media, policy—to redress the wounds of yesterday and protect the dreams of tomorrow.

The story of slavery in Texas is not one that ends with emancipation. It is a story that moves through resistance, through rebuilding, through reinvention. It is echoed in every Black child learning their ancestry, in every entrepreneur reclaiming stolen land, in every elder who remembers and reminds. It lives in every drumbeat, sermon, protest, and blueprint. It is a story without a neat conclusion, because the work is not finished. But it is also a story of victory—not the victory of erasure, but of endurance.

To walk through Texas as a Black person today is to walk with ghosts and gods. The land remembers, the streets remember, and the people remember. And yet, they build. They sing. They educate. They heal. They dream. They organize. They vote. They write. They plant. They resist. They liberate.

And so, this final act closes not with a curtain but with a call—to memory, to movement, and to the eternal flame of Black liberation. From the chains of Galveston to the parades of Juneteenth, from the shackles of the plantation to the summit of resistance, the people who were never meant to survive have not only survived—they have led. They are still leading.

They are the thunder before the storm. They are the storm. They are the architects of the new Texas.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

Washington D.C.

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad