Slavery in what is now West Virginia was never merely an auxiliary institution of the South—it was deeply woven into the state's early economy, politics, and social structures, despite its mountainous geography and smaller plantations. The institution began in the early 18th century as settlers crossed the Allegheny Mountains, bringing with them the enslaved labor systems of Virginia’s Tidewater and Piedmont regions.

Although West Virginia would not become a separate state until 1863, its involvement in and benefit from the slave system long predated its statehood and persisted in varied forms after emancipation. From slave auctions on courthouse steps in Martinsburg and Lewisburg to salt mines and iron furnaces powered by Black labor in Kanawha Valley, slavery was a linchpin in West Virginia's development.

Despite the myth that geography shielded West Virginia from the institution’s cruelties, the facts prove otherwise. Enslaved people in West Virginia worked in agriculture, mining, domestic service, timber production, salt extraction, iron smelting, and railroads. Their bondage was enforced by law, custom, and violence, and its legacy continues to affect descendants through systemic disparities embedded in every institution of the state.

The peculiar institution in West Virginia took on forms that at times differed from the sprawling cotton plantations of the Deep South. Due to the terrain, most slaveholders in the region owned fewer than ten enslaved people. However, this did not diminish the depth of cruelty or the economic significance of enslaved labor. Particularly in the Kanawha Valley, enslaved people were forced into labor-intensive work in the region’s booming salt industry. By the 1840s, this area produced more salt than any other in the country.

Slaves worked waist-deep in brine pits, boiled the water in vast kettles, chopped wood to fuel the fires, and hauled the final product across treacherous terrain. Their labor enriched white salt barons, including families whose names still appear on buildings and civic institutions today. It was these industries—salt, timber, mining, and domestic servitude—that formed the core of the slavery industrial complex in West Virginia.

Unlike the stereotypical plantation fields of cotton or sugar cane, many enslaved West Virginians endured a form of bondage that mimicked modern industrial labor, often under even more physically degrading conditions. The salt furnaces operated nonstop and in shifts, leading to the use of enslaved labor at all hours. Over time, enslaved people were leased to salt companies in a practice that became extremely profitable. Leasing systems allowed slaveholders to profit from their human property without having to house or directly supervise them. In turn, companies enjoyed labor flexibility while avoiding the costs of full ownership.

This industrial use of human beings blurred the line between plantation agriculture and capitalism. This model of labor foreshadowed the rise of exploitative wage labor that would follow formal emancipation, especially in coal mining, where Black men were later recruited en masse, exploited, and often trapped in economic bondage through company scrip and housing systems eerily reminiscent of slavery.

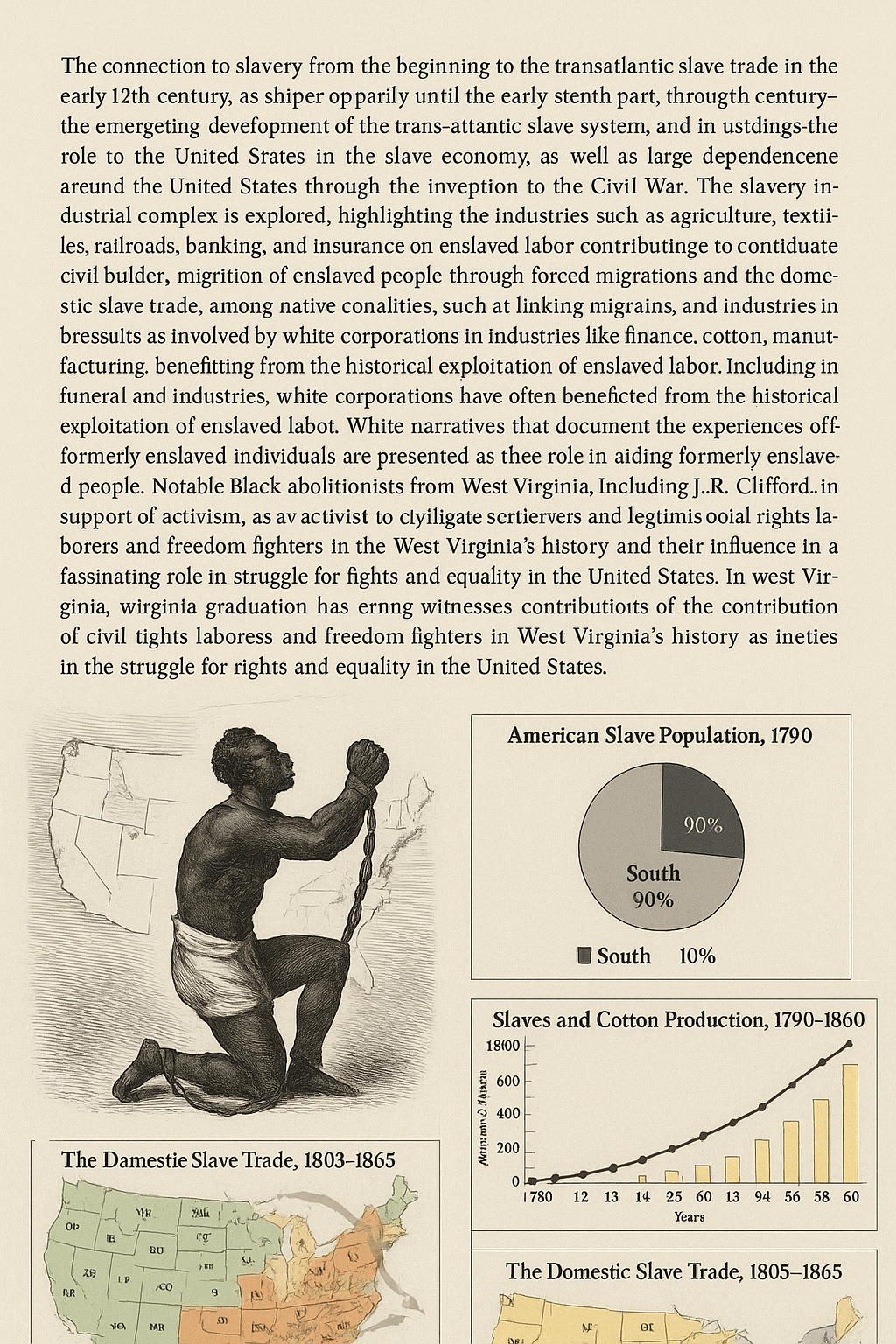

Slave migration into and out of West Virginia played a pivotal role in shaping the state's demographics and economy. Many enslaved people were forcibly brought into the region from eastern Virginia or further south as the salt and iron industries grew. Others were bred for sale in western Virginia’s slave markets, contributing to the internal slave trade that devastated countless families. Even before statehood, counties such as Jefferson, Berkeley, Kanawha, and Greenbrier became active centers of the slave economy, linking West Virginia to the broader Southern slave infrastructure.

After Nat Turner’s 1831 rebellion, Virginia passed stricter slave codes that affected western counties as well. These laws banned literacy, prohibited gatherings, and increased surveillance, reflecting white anxieties over insurrection and asserting state control. West Virginia was not immune to these dynamics; fear of rebellion was pervasive, and militias were established in towns like Clarksburg and Wheeling to suppress potential uprisings.

The march toward emancipation was complicated in West Virginia by its dual identity. As the Civil War erupted and western Virginians split from the Confederacy to form a new state, the issue of slavery remained divisive. Many Unionists in the region were also slaveholders, and the new state’s admission to the Union in 1863 was only granted after a compromise that included gradual emancipation. Slavery was not fully abolished in West Virginia until early 1865, months before the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

This incrementalism reflected the political power of enslavers even in a supposedly Unionist state. When the Freedmen’s Bureau established operations in West Virginia after the war, it was immediately inundated with reports of forced labor, violence, and withheld wages. Though relatively under-resourced in the state, the Bureau attempted to mediate labor contracts and provide some basic services. However, with no significant federal troop presence and widespread hostility from white locals, its power was limited.

Numerous slave narratives from West Virginia provide first-hand testimony to the brutality and endurance of enslaved people in the region. One such narrative comes from Fountain Hughes, who was born into slavery in Charlottesville, Virginia, and whose family had members taken to West Virginia. In his later-life recordings, Hughes vividly describes the stripping of identity, the terror of beatings, and the indignity of being denied even the memory of his own parents.

While Hughes ultimately settled elsewhere, his story was repeated across the hills and valleys of West Virginia, where generations of Black families would try to reconstruct their history despite deliberate erasure. Another powerful testimony comes from the descendants of Hannah Christmas, enslaved in what is now Mercer County, whose family retained oral traditions and eventually published their history. Such narratives, though often lost to the ravages of time, underscore the importance of Black storytelling in resisting the amnesia imposed by white supremacy.

The story of West Virginia’s Black abolitionists is not widely known but is nevertheless remarkable. John F. Cook Sr., though originally from Washington D.C., had deep ties to African American educational and religious circles that extended into West Virginia. He and others like him helped create a network of resistance that included Black churches, mutual aid societies, and underground rail routes that passed through the state’s terrain.

Another notable figure is William H. Davis, a Black teacher, journalist, and activist who fought for the rights of freedmen in the state and advocated for equal education. As a leader in the West Virginia Colored Teachers Association, Davis represented the Black intellectual and activist class that emerged during Reconstruction, determined to seize the promise of freedom even in the face of systemic violence.

Civil rights labor in West Virginia did not end with emancipation. In the early 20th century, Black coal miners became essential to the state’s labor movements, particularly during the mine wars. The Battle of Blair Mountain, one of the largest labor uprisings in U.S. history, involved thousands of miners, including many Black workers, fighting not only for labor rights but against racist systems of segregation within the union itself.

The United Mine Workers of America (UMWA), under pressure from Black and immigrant members, eventually adopted more inclusive practices. Still, racial discrimination remained rampant. Nonetheless, Black workers played key roles in organizing strikes, publishing newsletters, and advocating for fair treatment. Their labor activism created a legacy of struggle that persists in contemporary West Virginian movements for environmental justice and economic reform.

The story of West Virginia’s slavery legacy cannot be told without addressing the continued economic benefits white-owned corporations have reaped from slavery and its aftereffects. Many of the state’s largest industrial and landholding entities—from timber companies to coal conglomerates—trace their wealth to origins that included enslaved labor.

Corporations such as the Kanawha Salt Company were built directly on the backs of enslaved people. Later, when industries transitioned to wage labor, they employed exploitative systems that disproportionately affected African Americans, including discriminatory hiring, unequal pay, and redlining. These same companies often invested in segregated schools, hospitals, and neighborhoods, ensuring that Black West Virginians remained second-class citizens. Even today, the wealth gap between Black and white families in West Virginia remains vast. Access to quality housing, education, and healthcare is still stratified along racial lines, a direct consequence of generational disenfranchisement.

The financial institutions that serviced the slave economy—through mortgages on enslaved people, insurance on slave laborers, and the leasing of human beings—are not relics of the past. Some have merged into banks and firms that operate today. Though many companies have yet to fully acknowledge their roles, investigations and genealogical research have traced corporate lineages back to firms that profited directly from the sale, trade, and labor of enslaved West Virginians. The West Virginia economy was shaped in part by these practices, and their effects have rippled outward across generations, manifesting in disproportionate incarceration rates, underfunded schools, and limited capital access in Black communities.

In recent years, movements in West Virginia have begun to challenge these legacies. From calls for reparations to efforts at public memorialization, such as historic markers for Black cemeteries and preservation of freedmen’s schools, Black West Virginians are reclaiming their past. Academic institutions have also begun confronting their ties to slavery. Marshall University and West Virginia University have both faced scrutiny over their historical connections to enslavers and have launched limited initiatives to explore these histories. However, much work remains to be done. A comprehensive reckoning with West Virginia’s slavery legacy would require land reform, reparative justice, investment in Black communities, and widespread public education about the state’s true history.

This history is not simply a story of pain and injustice—it is also a testament to resistance, resilience, and the enduring power of a people who refused to be erased. The blood and labor of enslaved West Virginians fertilized the land and built the infrastructure of a state that would later claim to be a bastion of independence. That contradiction must be confronted with honesty. To ignore it is to betray the memory of those who endured. To remember it is to affirm the humanity, strength, and unyielding spirit of Black West Virginians past and present. As this history continues to be unearthed, told, and honored, a more truthful and just West Virginia may finally come into view.