The creation of Washington, D.C. as a federal district in 1790 brought with it the political and legal baggage of the neighboring slaveholding states of Maryland and Virginia. Both had long-standing slave systems, and both contributed land and culture to the new capital. Consequently, slavery in the District operated under a unique amalgam of laws and customs from those two states. Slavery became embedded in the economic and political life of the city, despite being a place where national lawmakers regularly debated issues of liberty. The contradiction was glaring, and yet the economy of early Washington depended heavily on enslaved labor. Government buildings, private homes, roads, and gardens were all constructed and maintained by enslaved African Americans.

By the early 1800s, Washington had become home to a thriving slave market. The city boasted several notorious slave pens, including those operated by Franklin and Armfield, one of the most powerful slave-trading firms in the United States. From Washington, enslaved people were sent to the Deep South in what became known as the domestic slave trade. This forced migration separated families and contributed to the massive relocation of enslaved individuals from the Upper South to cotton-producing regions in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. D.C. became both a source and conduit in this violent redistribution of Black bodies.

Washington’s legal environment enabled and reinforced the institution. Because it was not a state, the District’s laws on slavery were subject to Congressional oversight, and the federal government often failed to act decisively on abolitionist petitions. Enslaved individuals had few legal protections. Fugitive slave laws ensured that escape from slavery remained perilous, even within the boundaries of the capital. Public auctions and advertisements for runaways were common in local newspapers, reflecting how deeply the city was entangled in the commerce of slavery.

Despite this oppressive environment, Washington, D.C. was also a center of resistance. Free Black communities emerged in the city, and many members of these communities played pivotal roles in the abolitionist movement. Black churches, schools, and mutual aid societies formed a network of support for free and enslaved Black people alike. One of the most significant sites of Black empowerment in early D.C. was the Israel Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded in 1820. It became a vital center for both religious life and political organization.

Slavery’s defenders in Washington faced growing resistance from abolitionists both Black and white. In 1835, the city experienced what became known as the Snow Riot, a white supremacist backlash against Black economic success and the growing abolitionist movement. The riot targeted Black businesses and churches, laying bare the violent tensions surrounding race and slavery in the nation’s capital. Nevertheless, activists persisted. Abolitionists flooded Congress with petitions demanding the end of slavery in D.C., though the "gag rule" of the 1830s and 1840s stifled debate for many years.

By the mid-19th century, the District became a flashpoint in the national debate over slavery. The Compromise of 1850, a package of laws intended to quell sectional tensions, included the abolition of the slave trade—but not slavery itself—in Washington, D.C. This legal change did little to improve conditions for those still held in bondage. The trade may have been prohibited, but the practice continued, with enslaved individuals still bought and sold through covert or relocated means.

The Civil War transformed the landscape of slavery in D.C. In 1862, nine months before the Emancipation Proclamation, Congress passed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act. This legislation freed over 3,000 enslaved persons in the District and offered financial compensation to their former owners. It was the only such program in the United States. Though celebrated by many, the act also underscored the continuing devaluation of Black life, as freedom had to be purchased through the appeasement of enslavers. Still, it marked a significant step toward abolition and inspired widespread celebration within D.C.’s Black community.

Following emancipation, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a strong presence in Washington, D.C., helping formerly enslaved individuals transition to life as free citizens. The Bureau provided food, housing, education, and legal assistance, although it was chronically underfunded and often met with white resistance. Nevertheless, many freedmen and women seized the opportunity to educate themselves and their children. The city became a beacon for African Americans in search of opportunity, and its Black population swelled in the post-war years.

Black education and intellectual life flourished in the District, particularly with the founding of Howard University in 1867. Created with the assistance of the Freedmen’s Bureau and named after its commissioner, General Oliver O. Howard, the institution aimed to provide higher education to African Americans. It quickly became a cornerstone of Black intellectual, cultural, and political life, producing generations of leaders, activists, and scholars. Howard remains one of the most prominent Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) in the nation.

The legacy of slavery in Washington also shaped its economic and corporate landscape. Some of the city’s oldest institutions and industries—banks, law firms, and real estate companies—either directly benefited from slavery or were founded by individuals who amassed wealth through slaveholding. Traces of this legacy remain in corporate endowments, family fortunes, and land holdings. Several white universities in the District, including Georgetown University, have acknowledged their historical ties to slavery. In 1838, the Jesuit priests who ran Georgetown sold 272 enslaved men, women, and children to keep the school financially afloat. The legacy of that sale continues to reverberate, with ongoing efforts to address the moral and financial implications of that history.

Washington, D.C. also birthed some of the most courageous Black abolitionists and freedom fighters in American history. Frederick Douglass, though born in Maryland, made his home in D.C. for much of his later life and used the city as a base for his advocacy. His home in the Anacostia neighborhood remains a national historic site. Charlotte Forten Grimké, a prominent abolitionist and educator, also lived in D.C. and worked to uplift the Black community. The city was a magnet for Black reformers, educators, and politicians during Reconstruction and beyond.

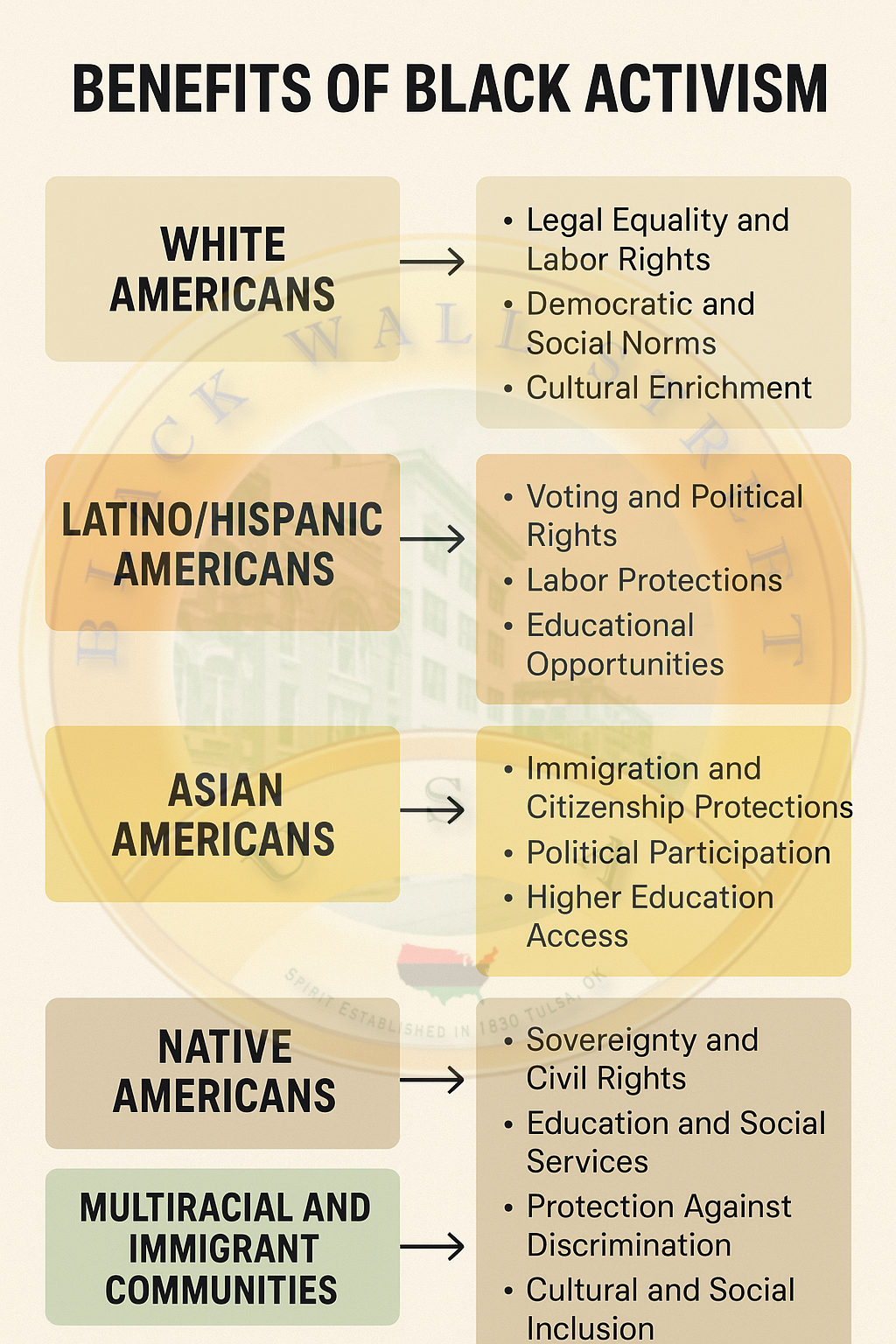

Civil rights labor in the 20th century drew heavily on D.C.’s legacy of Black resistance. From the New Negro Movement of the 1920s to the March on Washington in 1963, D.C. has remained a vital center for Black activism. Figures such as Mary Church Terrell, a co-founder of the NAACP and one of the first African American women to earn a college degree, made D.C. their home. Terrell worked tirelessly for suffrage, education, and civil rights, bridging the gap between post-Emancipation struggle and the modern civil rights movement.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, efforts to acknowledge and redress the legacy of slavery in Washington, D.C. have gained momentum. Community organizations, scholars, and activists have worked to uncover and preserve the city’s Black history, often hidden beneath official narratives. Public markers, museum exhibits, and educational initiatives now increasingly reflect the truth of slavery’s imprint on the District.

Nonetheless, the structural inequalities forged by slavery endure. Economic disparities, educational gaps, and housing segregation in D.C. continue to reflect the historical realities of racial oppression. The effects of generational trauma and systemic racism cannot be divorced from the city’s origins in slavery. Black communities in D.C. have fought for generations not only for civil rights but for basic survival in the face of displacement, gentrification, and economic marginalization.

Washington, D.C.’s story of slavery is one of complexity and contradiction, but also of resilience and hope. It is a story of a capital built on the backs of the enslaved, yet reclaimed by their descendants through struggle, intellect, and faith. The fight for justice in the nation’s capital is far from over, but it is deeply rooted in a long tradition of Black resistance that began the moment the first enslaved person was forced to labor on its soil. The memory of slavery in D.C. is not merely a chapter in the past but a living thread woven into the fabric of its present and future.

Modern-day Washington, D.C. continues to grapple with the legacies of slavery through public policy debates and grassroots activism. Organizations such as the DC Justice Lab, Black Lives Matter DC, and the Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs actively work to dismantle systemic inequities rooted in centuries of exploitation. These modern movements draw inspiration from the abolitionists and civil rights warriors of previous centuries, keeping alive the struggle for racial justice through legal reform, community mobilization, and education.

The push for D.C. statehood is deeply intertwined with the historical disenfranchisement of its largely Black population. The denial of full voting representation in Congress to residents of the nation's capital echoes the earlier denials of freedom and humanity to enslaved people. Activists and lawmakers today highlight this contradiction as a continuation of a long pattern of exclusion and marginalization. The fight for representation has become yet another front in the broader battle to undo the enduring consequences of slavery.

Public memory in the District is slowly evolving to incorporate the fuller truth of its past. Institutions such as the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture offer in-depth explorations of the city’s—and the nation’s—relationship to slavery. Local initiatives are also underway to rename buildings, install plaques, and hold ceremonies that honor the contributions and suffering of the enslaved. Through these efforts, D.C. is beginning to reclaim its narrative, making space for stories long silenced.

Educational curricula across D.C. schools are being updated to more accurately reflect the city’s history with slavery and racial injustice. Teachers and community groups are working together to create resources that center Black voices and perspectives, ensuring that future generations understand not only what happened, but why it matters. This educational shift is crucial for building a more equitable future grounded in historical truth.

Economically, the legacy of slavery persists in wealth disparities that disadvantage Black residents. Real estate practices like redlining and racially restrictive covenants, which were used well into the 20th century, were undergirded by the same ideologies that justified slavery. Today, many of D.C.’s gentrified neighborhoods were once vibrant Black communities established by the descendants of the enslaved. The displacement of these communities in the name of urban renewal reflects the ongoing economic consequences of racial oppression.

Health disparities in D.C. also trace back to slavery’s legacy. Black Washingtonians experience higher rates of infant mortality, chronic illness, and lack of access to quality healthcare. These inequities are rooted in centuries of neglect and discrimination, dating back to the days when enslaved people were denied medical care or used as subjects for unethical experimentation. Addressing these disparities requires not only policy change but a reckoning with the historical injustices that created them.

The religious institutions founded by free and formerly enslaved Black people remain central to D.C.’s cultural and political life. Churches like Metropolitan AME and Shiloh Baptist have long served as bastions of community strength, places where spiritual nourishment met with political strategy. These churches were pivotal during the civil rights era and continue to be centers of social justice work today, linking modern struggles to historical roots.

The continued presence of monuments and names honoring enslavers and segregationists has prompted renewed calls for reexamination. Activists argue that true remembrance requires both honoring the enslaved and removing symbols that glorify their oppressors. The process of renaming schools, streets, and public spaces is ongoing and reflects a broader cultural reckoning with the past.

Through this ongoing evolution, Washington, D.C. remains both a microcosm and a mirror of the nation’s complex relationship with slavery. Its story is unfinished, shaped by new voices demanding recognition, justice, and transformation. The memory of slavery is not relegated to textbooks or museums; it lives in the very fabric of the city—in its laws, its streets, its people. Only through sustained and honest engagement with that memory can the nation’s capital become a true beacon of the ideals it was founded to represent.

Black women in Washington, D.C. played an indispensable role in both resisting slavery and constructing the social, political, and spiritual infrastructure of Black life in the capital before and after emancipation. Their resistance was often quiet but unrelenting, woven into daily acts of survival, cultural preservation, and protection of their families. Enslaved women in the District not only labored in homes, kitchens, and fields but also raised generations of children under the threat of sale or violence.

These women were often the linchpins of kinship and resistance networks, passing down oral histories, spiritual knowledge, and coded warnings through lullabies, prayers, and food traditions. Their courage under constant surveillance and systemic dehumanization laid the foundation for generations of activism to follow.

Women such as Alethia Tanner, an enslaved woman who bought her own freedom and that of several family members in the early 19th century, became prominent figures in early Black Washington. She was a major contributor to the founding of the first independent Black church in the city, and she used her earnings from market vending to fund Black education and religious institutions. Her name is etched into the memory of a city still reckoning with how much it owes to the faith and determination of such women.

During the years of slavery, free Black women often used their tenuous legal status to support both enslaved and fugitive individuals. Women like Ann Dandridge and Louisa Parke Costin navigated their marginal freedoms to establish schools for Black children at a time when even literacy for African Americans was considered dangerous. Costin, born to a free Black mother and an enslaved father owned by George Washington's family, founded one of the earliest documented schools for free Black children in D.C. Her legacy exemplifies how women used education as a tool of resistance and liberation.

Following emancipation, Black women continued to lead. They served as teachers in the Freedmen’s Bureau schools, nurses for the sick and war-wounded, and organizers of mutual aid societies. The National Association of Colored Women (NACW), founded in 1896 with headquarters in Washington, D.C., became one of the most powerful Black women's organizations in American history. Its motto—“Lifting as We Climb”—embodied the mission of women like Mary Church Terrell, who was among its founders. Terrell advocated for racial and gender justice and worked tirelessly for the rights of Black domestic workers, many of whom were the daughters and granddaughters of enslaved women.

Women’s clubs and community circles blossomed throughout the District in the early 20th century. These organizations offered social services, organized political campaigns, and established schools, clinics, and libraries in Black neighborhoods. The Colored Women's League of Washington, another pioneering group, addressed issues from sanitation to suffrage. Their activism formed the backbone of the larger civil rights struggles to come.

Religious women leaders were also critical. Women’s missionary societies and prayer circles funded churches, provided housing for migrants from the South, and served as informal labor networks. Their work was not always recognized in male-led church hierarchies, but their influence was undeniable. Churches like Lincoln Temple and Fifteenth Street Presbyterian thrived not only because of their pastors but because of the tireless fundraising, community organizing, and childrearing led by their women members.

This tradition of women-led activism continues today. Contemporary organizations such as the Black Women’s Health Imperative, headquartered in Washington, D.C., advocate for the wellbeing of Black women and girls—physically, economically, and politically. The legacies of those who endured enslavement and oppression continue to shape the moral and civic architecture of the city through the leadership of women who refuse to forget, remain silent, or stop organizing.

In the postbellum period, as Washington, D.C. transitioned from a city built on slave labor to one struggling with the contradictions of Reconstruction and Jim Crow, Black working-class communities and laborers became central to the shaping of the city’s economic and social fabric. The end of formal slavery did not translate to equity or justice in the workplace. Black workers were largely relegated to the lowest-paid, most physically demanding, and least secure jobs—positions that were both a continuation of the roles they held under slavery and an outgrowth of white supremacist labor hierarchies that denied them fair wages and upward mobility.

The construction, domestic, streetcar, sanitation, and service sectors were the primary employers of Black men and women in postbellum Washington. Enslaved Black men had once built the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the early layout of the city’s infrastructure; their descendants continued this legacy in segregated job categories with limited protections. Black women, many of them formerly enslaved or born to freed parents, found work mostly as maids, nannies, laundresses, and seamstresses in white households. The city’s Black domestic labor force was enormous, invisible in most historical records but indispensable to the comfort and productivity of Washington’s white elite.

Yet even amid these constraints, the Black working class in Washington organized. Labor unions, initially hostile to Black workers or entirely exclusionary, were eventually challenged by Black-led labor organizations and multiracial coalitions. The Colored National Labor Union (CNLU), founded in 1869 in D.C. by Isaac Myers—a free Black ship caulker from Baltimore—was one of the first national attempts to unify Black labor. Myers, alongside Frederick Douglass who later served as CNLU president, sought to advocate for full inclusion of Black workers in the economic life of the country. The CNLU’s presence in Washington was strategic; the capital city served as a hub of federal employment, Black media, and civic activism.

Although the CNLU faced internal and external resistance—including from the white-dominated National Labor Union which refused to fully embrace racial equality—its existence inspired the formation of local Black labor clubs and mutual aid societies in Washington. These groups organized around issues such as job training, fair wages, housing rights, and protection from racist employment practices. In 1881, Black waiters and cooks at Washington hotels went on strike to demand better pay and treatment, an action that sparked similar uprisings across the hospitality sector in the city.

Legal resistance also grew alongside labor activism. In the courts, Black Washingtonians fought discrimination, defended their property rights, and challenged exclusion from public services. The District’s unique political status as a federal jurisdiction created unusual legal conditions, sometimes limiting and sometimes enabling challenges to segregation and labor exploitation. One such legal pioneer was John F. Cook Jr., a free Black man whose father had been born enslaved. Cook served as a lawyer, educator, and activist, fighting against laws and ordinances that disadvantaged Black D.C. residents.

Another notable legal effort was the landmark case of Bolling v. Sharpe in 1954. Though it came decades after the Civil War, it traces its roots to the long legal battles waged by Black Washingtonians over unequal schools and public accommodations. The case involved Black children in Washington, D.C. who were denied admission to white public schools. Bolling v. Sharpe became the companion case to Brown v. Board of Education, and together, they led to the Supreme Court’s historic ruling against school segregation. The inclusion of Bolling was critical because D.C., as a federal territory, was not bound by the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause—but the Court ruled that the 5th Amendment’s Due Process Clause also forbade racial discrimination, extending constitutional protections to D.C.’s Black residents.

Earlier legal resistors like Charlotte Dupuy, who had sued for her freedom in the early 19th century while enslaved by Henry Clay, and William Costin, who challenged D.C. authorities over Black property rights, laid the foundation for such modern victories. These cases revealed a tradition of legal literacy and strategic resistance among Black D.C. residents, many of whom understood the law not as a neutral system but as a terrain of struggle in the fight for dignity and equality.

The interplay between Black labor activism and legal resistance in Washington, D.C. formed a crucial nexus of Black civic life. Black workers organized to demand wages that reflected their humanity. Black legal minds shaped and reshaped the terrain of freedom through courtrooms and civic campaigns. Together, they created a model of resistance that was both systemic and deeply rooted in community solidarity.

The foundation of Black educational institutions in Washington, D.C. was not simply an educational endeavor—it was a radical act of self-determination and resistance. In the decades following emancipation, Black Washingtonians recognized that literacy, higher learning, and vocational training were essential tools in their struggle for liberation. The nation's capital, as a symbolic and political heart of the country, became fertile ground for a network of Black schools and colleges that would shape generations of leaders, activists, clergy, and professionals.

No institution better embodies this tradition than Howard University. Established by an act of Congress in 1867 and named after General Oliver O. Howard of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Howard was originally intended as a theological seminary for educating Black ministers. However, it quickly expanded its mission to provide liberal arts, professional, and graduate education to Black students across the country and beyond. It became the flagship historically Black college or university (HBCU), sometimes referred to as “the Mecca” of Black intellectual and cultural life.

Howard University’s law school trained many of the legal minds who would later dismantle Jim Crow segregation. Charles Hamilton Houston, dean of the Howard Law School in the 1930s, fundamentally transformed the curriculum to prepare students for civil rights litigation. Houston mentored Thurgood Marshall, who would go on to become the first Black U.S. Supreme Court Justice and the lead counsel in Brown v. Board of Education. But their roots were in Washington, D.C., where both men understood the law as a tool for racial justice.

Beyond the law, Howard served as a beacon for Black doctors, nurses, engineers, teachers, artists, and theologians. The university’s College of Medicine was one of the few places in the country where Black Americans could train as physicians in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its graduates formed the backbone of Black hospitals and clinics throughout the South and D.C., especially at a time when segregation barred Black patients from white facilities. Similarly, Howard’s School of Divinity and College of Fine Arts nurtured generations of Black ministers, musicians, and writers whose cultural work shaped the nation.

Howard’s student body itself became an agent of political change. The campus was a hotbed of protest, intellectual experimentation, and national organizing. Students mobilized against apartheid, against the Vietnam War, against racism in education and housing, and for the expansion of civil rights protections. In the 1960s and 70s, student movements on Howard’s campus linked arms with labor unions, political organizations, and faith leaders to demand a transformation of Washington’s civic life. The sit-ins, marches, and demands for curriculum reform launched at Howard mirrored and, at times, guided national movements.

Surrounding Howard were primary and secondary schools that, while often under-resourced, were staffed by some of the most dedicated Black educators in the country. Black teachers, many of them Howard graduates or trained at the Miner Normal School (a teacher’s college for Black women founded in 1851), carried forward a tradition of excellence and racial uplift. These educators taught more than reading and arithmetic; they taught resistance, cultural pride, and civic responsibility.

Just as educational institutions nurtured the mind and sharpened strategy, Black faith institutions nurtured the soul and galvanized collective action. From the earliest days of slavery and through the Reconstruction and Jim Crow periods, Black churches in Washington served as sanctuaries, political headquarters, mutual aid societies, and training grounds for leadership. In a city steeped in political theater and bureaucracy, Black churches were often the only spaces where ordinary Black citizens could speak freely, plan bold actions, and engage in transformative organizing.

Metropolitan AME Church, founded in 1838, stands as a monument to this legacy. Known as the “National Cathedral of African Methodism,” the church hosted Frederick Douglass’s funeral in 1895 and has since welcomed generations of Black political leaders, from Booker T. Washington to Barack Obama. Metropolitan AME was more than a place of worship; it was a space where the strategies of protest and policy were conceived. Its pulpit carried the weight of both divine authority and civic urgency.

Similarly, the historic Shiloh Baptist Church, founded in 1863 by formerly enslaved people, played a key role in education, social services, and civil rights mobilization. The church ran literacy programs and mutual aid services for newly freed Black residents who had arrived in D.C. after the Emancipation Proclamation. Throughout the 20th century, Shiloh’s members were deeply involved in anti-lynching campaigns, desegregation efforts, and urban housing struggles.

The collective work of these churches extended beyond their walls. Black faith leaders in D.C. often served as intermediaries between government officials and grassroots communities. They helped channel grievances into policy demands, and at times, they sheltered those persecuted by the state. Churches raised bail for jailed protesters, housed migrants and the unhoused, and hosted voter registration drives. Many Black pastors were also members of national religious organizations that shaped the direction of the civil rights movement, including the National Baptist Convention and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

These educational and religious institutions were not separate silos—they were intimately connected. Howard professors preached in local churches. Church congregations raised money for scholarships. Black students brought their organizing training from campus into the pews, while sermons delivered in churches echoed in the slogans chanted in protest marches. The fusion of Black education and Black spirituality created a formidable foundation for political action.

Together, Black educational and religious institutions in Washington, D.C. constituted a parallel society—one rooted in dignity, intellectual rigor, spiritual depth, and unflinching resistance. They defied the false narrative of Black inferiority imposed by centuries of slavery and systemic racism. They reminded their communities that freedom was not just a legal status—it was a continuous practice, taught in classrooms, shouted from pulpits, and lived in the streets.

Black women in Washington, D.C. have long stood at the intersection of multiple forms of oppression, including racial, gendered, and economic exploitation. Yet from the earliest days of the capital’s formation, they also embodied resistance, organizing, and transformative leadership in the face of bondage and inequality. Their contributions to abolition, education, labor, civil rights, and Black family and community life are vast, though often overshadowed in dominant narratives. Their resilience and innovation made them central actors in the long struggle against slavery and its aftermath.

During the antebellum period, free Black women in D.C. created social and mutual aid networks to support each other and provide shelter to those escaping slavery. They were seamstresses, washerwomen, cooks, and caregivers—not just laboring to survive but also leveraging their meager wages to establish schools, churches, and safe havens. These women often faced the daily terror of kidnappers who roamed the streets of Washington, abducting even free women and children and selling them into slavery across state lines. Still, they organized. In their homes, they passed along abolitionist literature, taught literacy in secret, and sustained oral traditions that preserved cultural memory and hope.

The role of Black women educators in Washington, D.C. is particularly significant. Myrtilla Miner, a white woman abolitionist who founded the Miner Normal School in 1851, often receives credit for expanding educational opportunities for Black women in the capital. However, it was Black women educators such as Lucy Addison, Anna J. Cooper, Mary Church Terrell, and others who sustained, professionalized, and radically reimagined education for generations of Black Washingtonians. They turned schools into civic centers, launching leadership training programs and emphasizing classical education and Black history in defiance of white supremacist policies and textbooks.

Anna Julia Cooper, born enslaved in North Carolina in 1858, became one of the most influential Black scholars and educators in American history. After receiving her doctorate from the Sorbonne, she returned to D.C. and led the M Street High School (later Dunbar High School), one of the most rigorous public high schools for Black students in the nation. Her work embodied the radical idea that Black children were not only capable of academic excellence but entitled to it. Her 1892 book A Voice from the South framed Black women as intellectual and moral leaders of their communities—a position she herself modeled for decades in Washington.

Mary Church Terrell, another towering figure in D.C., was among the first Black women to earn a college degree and a lifelong advocate for racial and gender justice. As a resident of Washington and a member of the city's Board of Education, she used her position to challenge both educational inequality and broader structural racism. Terrell was also a co-founder of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), which formed in D.C. in 1896 and took as its motto “Lifting As We Climb.” This organization, grounded in the local activism of D.C.’s Black women, aimed to counter racist depictions of Black womanhood and provide real services—such as job training, child care, and political education—to the city’s Black working class.

Terrell, Cooper, and others organized with strategic brilliance. They challenged segregationist policies in restaurants, parks, and theaters through public protests and lawsuits. One of the most important early civil rights cases—District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co.—involved Terrell’s activism, which challenged the segregation of D.C. restaurants and resulted in a 1953 ruling upholding the right of Black patrons to dine in establishments that served the public. Her legal resistance was built upon decades of grassroots organizing by D.C.’s Black women.

The activism of Black women in the capital also played out in the domestic sphere. Domestic workers—maids, nannies, and cooks—often faced grueling labor conditions, sexual violence, and near-total economic dependence on white families. Yet they formed unions, refused abuse, and passed survival skills from mother to daughter. Organizations such as the National Domestic Workers’ Union of America, led in part by D.C.-based women in the mid-20th century, created networks of resistance and political education that allowed thousands of women to negotiate better pay and demand dignity on the job.

Black women in the city’s religious life were also crucial actors. Women’s missionary societies, church auxiliaries, and choirs were more than religious institutions—they were political ones. They raised money for legal defenses, supported boycotts, and trained girls and women in public speaking and organizing. Churches like Mount Zion United Methodist Church and Nineteenth Street Baptist Church housed strong women’s ministries that tackled housing insecurity, hunger, education, and voter registration. These ministries served as crucibles for Black feminist political thought, long before it had a name.

The modern civil rights movement in D.C. was similarly powered by Black women’s leadership. Although male ministers and spokesmen often received the spotlight, it was women like Dorothy Height, president of the National Council of Negro Women (headquartered in D.C.), who helped plan the 1963 March on Washington and maintained bridges between movements. Height organized poor Black women in the South and in D.C.’s inner-city neighborhoods, advocating for political and economic rights on a national scale. She advised presidents but never lost touch with the grassroots.

Black women in D.C. also led in media, policy advocacy, and academia. Journalists like Ethel Payne, who lived in Washington and reported for the Chicago Defender, challenged White House officials during press briefings and reported from the front lines of Black struggle. Black women staffers in Congress, though often invisible, drafted legislation, organized hearings, and lobbied for civil rights policies. In all of these spaces—often as the only Black woman in the room—they wielded influence, built coalitions, and reshaped the city’s power structures.

The legacy of these Black women continues in contemporary movements. From school board fights to anti-gentrification campaigns, from reproductive justice organizing to mutual aid during COVID-19, Black women in D.C. remain the architects of resistance and the heartbeat of the city’s Black political life. They carry the memory of slavery’s trauma while building futures grounded in dignity, joy, and justice. Their work in education, faith, law, labor, and activism is not a sidebar to D.C.'s history—it is its core.

Black journalism in Washington, D.C. emerged as both a sword and a shield—cutting through racial propaganda while defending Black dignity, community, and agency. In the years after the Civil War and Reconstruction, as the District’s Black population swelled and white supremacist backlash intensified, the Black press in D.C. became a vital forum for advocacy, literacy, organizing, and resistance. From church bulletins to nationally circulated newspapers, Black Washingtonians relied on their own words to shape their truth and fight the lies spread by mainstream white media. At the center of this journalistic renaissance was The Washington Bee.

Founded in 1882 by African American printer and civil rights activist William Calvin Chase, The Washington Bee was the longest-running Black newspaper in Washington during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Bee became a fierce and uncompromising voice for Black political rights, opposing segregationist laws, labor exploitation, and the disenfranchisement of Black D.C. citizens. It published biting editorials on national issues and local affairs alike, holding both white politicians and Black leaders accountable.

Unlike many white-run papers of the day that characterized African Americans as ignorant, dangerous, or inferior, The Washington Bee celebrated Black achievement, highlighted everyday community resilience, and made space for political critique. Its readership extended beyond the city to Black Americans across the country, linking Washington’s struggles to the national Black freedom movement. Chase himself often sparred publicly with Booker T. Washington over the latter’s accommodationist politics, instead promoting full civil rights and immediate access to education and the ballot for Black Americans.

In one notable 1901 editorial, The Bee wrote of the nation’s capital: “The Negro in Washington must not be silent. In the shadow of the White House, injustice still thrives.” This sentiment encapsulated the paper’s mission—to bear witness and provoke action. It took aim at segregation on D.C. streetcars, racial violence in the city, and the denial of voting rights to its Black residents. It encouraged readers to support Black-owned businesses, attend rallies, write to lawmakers, and protest unjust policies.

Beyond The Washington Bee, D.C. became home to a number of influential Black periodicals, magazines, and pamphlet publishers. The Washington Tribune, the New Negro Opinion, and the Afro-American's Washington bureau each played major roles in giving voice to the Black working and middle class. During the Harlem Renaissance and into the civil rights era, D.C.'s Howard University became a publishing center for radical thought, producing Black scholars, poets, and journalists who used print to dismantle white supremacist narratives and imagine a freer Black future.

Black women were also deeply involved in the journalistic life of the city. Writers like Mary Church Terrell contributed essays, letters, and speeches to the press that redefined what was considered “newsworthy” in a Black context. The National Council of Negro Women, based in D.C., operated its own newsletter and press office, ensuring that Black women’s voices and organizing efforts were not sidelined in public discourse.

However, just as Black journalism in D.C. rose to challenge structural racism and elevate community life, a new threat emerged in the form of land dispossession and gentrification—a modern iteration of the displacement that began under slavery and continued through Jim Crow urban planning.

The story of land and housing in Washington, D.C. is deeply racialized. During and after slavery, Black Washingtonians created communities in places white elites avoided—such as the swampy lowlands or the hills east of the Anacostia River. These neighborhoods, built on the labor and vision of Black families, were filled with Black-owned homes, churches, small businesses, and schools. Places like Barry Farm, Deanwood, LeDroit Park, and Shaw became centers of Black culture and survival.

However, beginning in the 20th century, the District’s Black communities were repeatedly uprooted under the banner of “urban renewal”—what James Baldwin more accurately called “Negro removal.” Highways and government buildings were built through once-thriving Black neighborhoods. Entire blocks were razed, and families who had owned land for generations were forced out, often receiving meager compensation or no compensation at all.

In the 21st century, this process continues under the guise of gentrification. Once neglected by developers and city planners, historically Black neighborhoods in Washington have become prime real estate. Rising property taxes, rent hikes, and speculative investment have forced thousands of Black families out of the city, hollowing out the communities that once stood as monuments to survival. Between 2000 and 2020, Washington, D.C. lost more than 20,000 Black residents, even as its overall population grew. The city once dubbed “Chocolate City” for its Black majority is now majority white.

This displacement mirrors the logic of the slave economy: that Black people’s lives, labor, and land are disposable when weighed against white capital. Just as enslaved people were sold and families torn apart to satisfy the economic appetites of white wealth, modern-day development in D.C. too often proceeds at the expense of Black existence. Neighborhoods that were starved of public investment now boast expensive condominiums, boutique coffee shops, and privatized green spaces—but the people who built and sustained those communities are gone.

And yet, resistance continues. Black-led organizations such as ONE DC, Empower DC, and the DC Tenants Union organize against evictions, demand community land trusts, and fight for affordable housing rooted in racial justice. Black journalists, including those working with outlets like The Washington Informer, DCist, and the Howard University News Service, continue to document these struggles, ensuring that the Black press remains a platform of truth and transformation.

Today’s Black journalists in D.C. inherit the legacy of The Washington Bee—not only telling stories, but shaping movements. Their work is to chronicle injustice, amplify resistance, and build collective memory, even as the physical spaces of Black D.C. are eroded. They carry forward the sacred task of keeping Black voices heard in the capital of a nation still struggling to reckon with its foundational sins.

In the post-Emancipation era, Black residents of Washington, D.C. consistently utilized the legal system as a battleground for justice, equality, and civil rights. The capital, although geographically Southern and socially segregated, held a unique legal and symbolic position. As the seat of federal power, D.C. became a stage where Black legal minds could test the elasticity of constitutional protections, and where activists could mount legal challenges that resonated across the nation.

Even before the official end of slavery, Washington’s Black residents were using the law to resist enslavement and inequality. In 1829, William Costin, a free Black man, challenged a city ordinance requiring Black residents to carry a “free papers” license. Costin, born of a formerly enslaved mother and a white father, owned property and worked as a messenger for the Bank of Washington. His legal battle, Costin v. City of Washington, though ultimately unsuccessful in overturning the ordinance, marked one of the earliest recorded cases of a Black Washingtonian resisting racially discriminatory laws in court. Costin’s case signaled that Black people in the District would not passively accept legal disenfranchisement.

After emancipation, Black legal resistance expanded through institutions such as the Howard University School of Law, founded in 1869 as one of the first law schools in the country to admit African Americans. It quickly became a training ground for a new generation of Black legal minds committed to civil rights. The school’s early graduates, such as James C. Napier and John Mercer Langston, combined legal training with political activism. Langston, who later served as the first Black dean of the law school and became a U.S. congressman, had previously defended fugitive slaves and lobbied against the Black Codes.

In the early 20th century, D.C. remained a segregated city, but the courts increasingly became a place where Black attorneys challenged unequal treatment. The formation of the Washington Bar Association in 1925, an organization of Black attorneys excluded from the white-dominated D.C. Bar, created a legal support network focused on civil rights litigation. Attorneys such as Charles Hamilton Houston, who would go on to transform the legal strategy of the NAACP, began his critical legal work in Washington. As vice-dean of Howard Law School, Houston mentored a cadre of legal minds, including Thurgood Marshall, who would later argue Brown v. Board of Education before the Supreme Court.

Washington, D.C. also produced significant civil rights litigation long before Brown. One such example is Corrigan v. Buckley (1926), a case involving a racially restrictive housing covenant in the Bloomingdale neighborhood of the District. Although the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the private right to enforce racially exclusive agreements, this case laid groundwork for future legal challenges. These covenants were widespread in the city and formed the legal infrastructure for redlining and Black displacement—forces deeply connected to the economic legacies of slavery.

Perhaps the most significant civil rights legal victory to emerge directly from Washington was Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), which arose when Black students were denied entry to the newly built John Philip Sousa Junior High School solely on the basis of race. Unlike Brown, which dealt with the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, Bolling relied on the 5th Amendment’s guarantee of due process, because the 14th Amendment technically did not apply to the federal government or its territories, such as D.C. The Supreme Court's ruling that racial segregation in D.C. public schools was unconstitutional extended the implications of Brown to the nation’s capital and affirmed that no arm of government could enforce segregation under constitutional principles.

Black legal resistance continued through the mid and late 20th century with attorneys like Margaret A. Burnham, A. Leon Higginbotham Jr., and Spotswood W. Robinson III—figures trained in the traditions of legal insurgency fostered in the District. These figures litigated cases challenging police brutality, employment discrimination, unequal school funding, and voting restrictions. They viewed the law not merely as a technical system but as a site of radical contestation, echoing earlier efforts by Costin and Langston.

Furthermore, community legal organizing in Washington became a powerful force. During the 1960s and 1970s, organizations like the Washington Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Urban Affairs, founded in 1968, began representing tenants, students, and low-wage workers in class-action lawsuits aimed at systemic discrimination. Public Interest law firms, often led or inspired by Black attorneys trained at Howard or involved in civil rights struggles, used the court to defend Black neighborhoods from displacement and criminalization.

Thus, the legacy of Black legal resistance in Washington, D.C. is neither episodic nor incidental—it is foundational. From early petitions for manumission and cases challenging discriminatory ordinances to landmark federal decisions like Bolling, Black attorneys and activists have wielded the law as a weapon against the aftershocks of slavery. Their legal strategies were both sophisticated and communal, built upon the understanding that in the capital of a nation founded on liberty, the battle for justice could not be postponed nor relegated to moral suasion alone—it had to be fought in the courts.

Washington, D.C. has long been a crucible of Black cultural innovation—a place where music, literature, theater, and visual arts have intersected not just as expressions of creativity but as instruments of resistance, truth-telling, and memory. From the spirituals sung in church basements to the street murals on Georgia Avenue, cultural production by Black Washingtonians has functioned as a vital archive of struggle and a defiant act against historical erasure.

The city’s cultural identity has been shaped by institutions and artists who refused to let the stories of enslavement, survival, and resistance fade into the background. Venues like the Howard Theatre, built in 1910, served as a safe haven for Black performance artists shut out of white establishments. Hosting legends such as Duke Ellington, a native son of Washington’s U Street Corridor, the theater became both a showcase of excellence and a gathering ground for community cohesion. Ellington’s music, steeped in the memory of Black migration and the afterlives of bondage, echoed the rhythms of a people who had resisted subjugation through sound.

U Street itself, often dubbed “Black Broadway,” functioned as a cultural artery for Black expression. During segregation, it was one of the few places in D.C. where Black people could enjoy nightlife, art, and political discussion without fear of white surveillance or exclusion. This corridor also gave rise to poets, painters, and photographers whose works challenged dominant narratives. It was a zone of creativity and critique—a space where resistance was rehearsed in verse and performance.

In later decades, the Black Arts Movement found fertile ground in D.C. through collectives such as the Black Arts Theater, the Studio Theatre, and visual art cooperatives that centered African and diasporic aesthetics. Artists like Sam Gilliam, Alma Thomas, and Lou Stovall infused the city’s cultural infrastructure with color, abstraction, and consciousness. Their work defied racist boundaries in both content and form, rejecting the idea that Black artistic production needed to be limited by realism or white tastes. Their exhibitions not only celebrated Blackness but called viewers to reckon with the long shadow of enslavement and dispossession.

The emergence of Go-Go music in the 1970s, with Chuck Brown at the helm, represents another form of distinctly D.C.-born Black cultural resistance. Go-Go was more than music—it was a localized expression of community identity that survived systemic neglect, school closures, and police harassment. Parties and backyard shows became intergenerational rites where stories were passed down, trauma was healed, and calls for liberation were encrypted in bass lines and percussion.

Murals and street art across Washington likewise tell a story of remembrance and resistance. The massive “Black Lives Matter” mural painted near the White House in 2020 during the George Floyd uprisings echoed earlier acts of spatial reclamation by Black artists. Street art became a form of protest that resisted erasure, claiming the city’s surfaces for Black grief, rage, and joy. These public works—whether memorializing enslaved ancestors or fallen youth—refuse silence. They make the past visible. They transform the city into a living museum of Black struggle and resilience.

Poets such as Sterling A. Brown and June Jordan, educators and literary warriors rooted in D.C., wrote verses that tied the nation’s capital to the legacy of plantation capitalism and the false promise of liberty. Their poems, published in local presses or read aloud at protests and readings, stitched personal loss to collective memory, challenging readers to confront the plantation foundations beneath Washington’s monuments.

Black cultural spaces like Busboys and Poets, named in honor of poet and activist Langston Hughes (who worked in D.C. as a young man), serve as modern bastions of creative political engagement. These spaces, part bookshop, part café, and part performance venue, are extensions of a long D.C. tradition of embedding cultural production in community empowerment. In these venues, young poets, filmmakers, and muralists continue the work of translating oppression into beauty, of alchemizing memory into resistance.

These cultural expressions are not merely decorative or retrospective. They are political. They are strategies of survival in a city where gentrification, policing, and public policy often conspire to mute Black voices. By making culture public and participatory, Black Washingtonians assert that history is not finished—that slavery is not merely a past institution but a lingering presence whose logic still structures property, value, and visibility.

This deep well of artistic resistance flows directly into the city’s ongoing struggle for statehood and self-determination. For generations, Black residents of D.C. have led the charge to end the city’s colonial status. Denied full representation in Congress and stripped of budgetary autonomy by federal oversight, D.C. has long functioned as a paradox: a capital of democracy where hundreds of thousands of its mostly Black residents are disenfranchised.

Political activism for D.C. statehood has always intersected with Black liberation. Leaders such as Marion Barry, Julius Hobson, and later Eleanor Holmes Norton positioned the struggle for home rule not simply as a procedural fix but as a civil rights demand. Barry, despite controversies, forged strong connections between the District’s working-class Black residents and political power, advocating for housing, jobs, and city control.

The 1973 District of Columbia Home Rule Act granted limited self-governance, including a local council and mayor, but Congress retained veto power and budgetary control. Black activists viewed this partial autonomy as a step forward but an insufficient remedy for a history of racialized exclusion rooted in the same ideologies that upheld slavery. D.C. activists framed their fight not in isolation but as part of the broader Black freedom movement—from abolition to civil rights to Black Lives Matter.

Modern coalitions, such as #51for51, led by young Black activists, frame statehood as a racial justice issue, arguing that D.C.’s lack of representation is not a constitutional oversight but a deliberate suppression of a majority-Black population’s voice. They point out that no other capital city in the democratic world is so completely controlled by a national legislature without equal representation. That contradiction is not incidental—it is inherited.

D.C. flags bearing the words “Taxation Without Representation” hang in windows and murals. But the fuller truth is that the taxation is not just financial—it is existential. The denial of statehood, in the eyes of many Black Washingtonians, is a continuation of the plantation logic that reduced Black people to bodies without rights, laborers without land, residents without voice. The fight for D.C. statehood is therefore more than a demand for a star on the flag; it is a rebellion against historical structures that began with slavery and continue through racist governance.

The Black cultural and political work in D.C. remains inseparable. Artists march beside legislators. Poets write statehood into existence. Musicians stage concerts as protests. Every mural is a ballot. Every drumbeat is a vote. Every story passed down in church or community center is a declaration that Black people in Washington, D.C. have not forgotten where they came from—and they are determined to shape where they are going.

The post-Emancipation journey of Black people in Washington, D.C., like in so many cities, has been marked by a battle over land—who owns it, who controls it, and who is displaced from it. The racial geography of D.C. was not incidental; it was engineered. Through housing segregation, land theft, and development schemes masked as “urban renewal,” Black Washingtonians were contained, relocated, and erased in ways that directly mirror the plantation-era mechanisms of spatial domination. In slavery, the enclosure of Black bodies served the economic interests of white landowners. In freedom, those enclosures persisted—repackaged as zoning laws, housing covenants, and redevelopment plans.

At the turn of the 20th century, many Black families in D.C. resided in alley dwellings—tight, unsanitary homes wedged behind white-owned buildings, out of public view but close enough for their labor to be extracted. These alleys, many of which had existed since the 1800s, were the spatial remnants of plantation logic: Black people hidden behind the grandeur of state architecture, confined to conditions that reproduced servitude under another name. City planners and white residents deemed these communities “slums,” justifying their destruction without replacing them with adequate or affordable housing.

In the mid-20th century, the federal government initiated aggressive “urban renewal” programs that razed entire Black neighborhoods. Southwest Washington, home to a dense and vibrant Black working-class community, was nearly obliterated in the 1950s and 60s. Under the guise of modernization, the area was condemned as blighted and subjected to eminent domain. Homes were bulldozed, churches demolished, businesses shuttered, and families uprooted. These renewal schemes did not renew Black life—they removed it.

This was not a unique event but part of a national pattern. What made D.C. particularly egregious was its symbolism: the capital of democracy destroying Black communities just blocks from monuments to liberty. The dispossession in Southwest echoed slavery’s theft of Black autonomy and its violent disruption of kinship networks. Families who had lived for generations in the same homes were scattered without recourse. The state held absolute power over their land—just as the enslavers once did.

The removal of Black communities through so-called redevelopment also signaled a transfer of value: Black land was devalued until it could be taken, then revalued once redeveloped for white residents and investors. This cyclical dispossession mirrors the economic logic of slavery, where Black presence generated value only insofar as it served white interests. When Black labor was deemed excessive, it was expelled. When Black homes were deemed obstacles to capital, they were erased.

Redlining further codified this spatial exclusion. Beginning in the 1930s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned neighborhoods in D.C. color-coded grades based on their perceived investment risk. Black neighborhoods were invariably marked in red—“hazardous”—making them ineligible for home loans and investment. This not only locked Black families out of generational wealth through homeownership but also ensured the physical decay of their neighborhoods, which was then used to justify further demolition or disinvestment.

Deed restrictions and racial covenants ensured that even Black people with money were restricted to segregated areas. Neighborhoods in upper Northwest and other affluent parts of the city openly excluded Black buyers, preventing upward mobility and spatial integration. These practices were the legal continuation of antebellum laws that forbade free Black people from owning property or settling near whites. The tools had changed—contracts replaced whips—but the purpose remained: control where Black people could live, how they could thrive, and whether they could claim the city as their own.

The struggle over land was not just about housing—it was about sovereignty. When Black communities fought back, they challenged a foundational aspect of white supremacy: the right to determine who belongs where. Organizations such as the National Committee Against Discrimination in Housing (headquartered in D.C.) and local tenants’ unions resisted these attacks, advocating for fair housing and community-led development. They understood that housing injustice was a form of racial violence deeply connected to slavery’s legacy of enclosure and dislocation.

In more recent decades, gentrification has emerged as a newer form of spatial control. Entire Black neighborhoods—Shaw, Columbia Heights, Anacostia—have experienced waves of development that push out long-term Black residents in favor of wealthier, often white, newcomers. The aesthetic of Black culture is preserved for tourism and branding, while its people are systematically removed. Go-Go music is celebrated in marketing campaigns even as Black-owned venues are priced out. Murals of Black heroes line the walls of luxury apartments that displaced Black elders. This is not transformation; it is repackaged dispossession.

The mechanisms of gentrification—rising rents, tax liens, predatory development deals—mirror the postbellum economic systems like sharecropping and debt peonage, which exploited the freedom of formerly enslaved people while keeping them economically and spatially confined. The state and private developers collaborate to ensure that land remains extractive, not emancipatory.

But the legacy of resistance endures. Land trusts, cooperative housing models, and organizing efforts by groups like Empower D.C. and ONE D.C. represent contemporary efforts to reclaim land as a site of Black autonomy. These movements understand that until Black people in D.C. have secure and equitable access to housing—land without threat—the ghost of the plantation will continue to loom over the nation’s capital.

Washington, D.C.'s Black educational institutions represent one of the most potent expressions of resistance to slavery's legacy and a vital mechanism for community empowerment, identity formation, and liberation. From the earliest makeshift classrooms established by freedmen in church basements to the world-renowned halls of Howard University, the city has been both a battlefield and a sanctuary for Black education. These institutions were born not only out of necessity but also as acts of defiance against the intellectual oppression that undergirded American slavery. They were designed to reverse generations of enforced ignorance and to cultivate the leadership and knowledge necessary to wage the struggle for justice.

In the immediate aftermath of Emancipation, the establishment of Black schools became one of the highest priorities for freed people. The Freedmen’s Bureau, founded in 1865, played a significant role in supporting education for formerly enslaved African Americans. In D.C., the Bureau facilitated the opening of numerous schools, often in partnership with Northern missionary societies and local Black churches. These schools offered basic literacy, arithmetic, and religious instruction, but more importantly, they instilled a sense of dignity and self-worth in students who had been denied personhood under slavery. The very act of learning to read was revolutionary; it had been illegal in many Southern states to teach enslaved persons to read or write.

Churches were among the first institutions to serve as educational spaces. The Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church, Israel Metropolitan CME Church, and other houses of worship hosted night schools and day classes for adults and children alike. Ministers and lay leaders taught by candlelight, often with borrowed textbooks and hand-me-down slates. These classrooms were more than places of learning—they were centers of communal resistance. In these sacred spaces, education became a form of worship, an affirmation of God's justice and a direct repudiation of the slaveholder's gospel that had sought to keep Black people ignorant and subjugated.

The Colored High School, later renamed the M Street High School and eventually Dunbar High School, stands as a pillar of Black academic excellence in D.C. and the nation. Founded in 1870, M Street High School became the first public high school for Black students in the United States. It attracted a remarkable faculty, many of whom held advanced degrees from prestigious universities in the North and abroad. The school produced a generation of African American intellectuals, lawyers, doctors, and civil servants who would shape the politics, culture, and civil rights movements of the 20th century. Dunbar graduates included Charles Hamilton Houston, who helped dismantle Jim Crow laws through legal strategy; Robert C. Weaver, the first Black cabinet member; and Anna J. Cooper, a towering feminist intellectual and educator.

Howard University, chartered in 1867, quickly became the crown jewel of Black higher education in D.C. and a national center of scholarship, leadership, and resistance. Founded with the mission to provide education in the liberal arts and professional fields to all races and both sexes, it became a haven for African Americans seeking higher learning in a nation still hostile to their freedom. Named after Union General Oliver Otis Howard, a white abolitionist and commissioner of the Freedmen’s Bureau, the university served as a partnership between Black aspirations and white philanthropy—though always with a tension around autonomy and control.

Howard's law school was especially significant. Charles Hamilton Houston, dean of the law school during the 1920s and 30s, transformed it into an incubator for civil rights legal strategy. He mentored Thurgood Marshall and a cadre of lawyers who would form the legal backbone of the NAACP and challenge segregation in courts across the country. Houston famously said he was training lawyers to become "social engineers" rather than "parasites on the community." The victories of the Civil Rights Movement were born in Howard's classrooms, in its legal debates, and in the strategic brilliance of its graduates.

But Howard was not the only institution of higher learning that played a pivotal role. Miner Teachers College, originally established as the Miner Normal School in 1851 by Myrtilla Miner, focused on training Black women to become teachers. Education for Black women was doubly radical: it challenged both racial and gender hierarchies. Miner’s institution, with its explicit mission to elevate Black communities through the training of teachers, became a major force in populating D.C.'s segregated but exceptionally well-run school system with qualified Black educators.

These educational institutions were not without their challenges. They were chronically underfunded, constantly attacked by racist detractors, and occasionally subject to paternalistic oversight by white philanthropists or government bodies. Nonetheless, they thrived because of the extraordinary dedication of Black educators, students, and communities who saw education as inseparable from the struggle for liberation. In a city that often denied Black people full citizenship, these schools affirmed their full humanity.

In the 20th century, the connection between education and activism deepened. Howard University became a center for Black student protest during the civil rights era. Students marched, organized sit-ins, and demanded the hiring of more Black faculty and the inclusion of Black Studies in the curriculum. The 1968 student takeover of Howard's administration building signaled a turning point in the Black Power movement in D.C., affirming the right of Black students to define the purpose and politics of their education.

Black educational institutions in D.C. also played a vital role in cultural development. Schools and universities hosted forums, concerts, lectures, and plays that celebrated Black heritage and interrogated white supremacy. The Howard Players theater group, for example, introduced audiences to the work of Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and other luminaries of the Harlem Renaissance. The Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, one of the largest repositories of African American history and culture, remains a national treasure housed at Howard.

Beyond formal institutions, D.C.'s Black education legacy also includes grassroots efforts: freedom schools, community workshops, literacy circles, and summer programs organized by activists and churches. These initiatives recognized that learning happens everywhere and that knowledge is a tool of survival and resistance. Even when public schools were systematically defunded or resegregated by housing policy, Black educators and families continued to innovate, creating environments where Black children could learn about themselves, their history, and their power.

Today, the struggle for equitable education in Washington, D.C. continues. Charter schools, gentrification, and testing regimes have reshaped the educational landscape, often displacing the very communities that built these institutions. Yet the legacy of D.C.'s Black educational pioneers endures. Their example reminds us that education is not just about degrees or diplomas—it is about freedom, memory, and the unyielding quest for justice.

As we look forward, the preservation and expansion of Black-led educational spaces in the District remain crucial. Reimagining schools as centers of Black culture, history, and liberation aligns with the tradition of those first freedmen who taught children in the shadows of slavery’s aftermath. Their vision persists in every classroom where a Black child is told their life matters, where their ancestors are honored, and where they are trained not only to navigate the world as it is, but to shape it into what it must become.

Washington, D.C., home to the very institutions of American democracy, has long stood as a paradox for Black Americans: a capital built on the labor of enslaved people, populated by a politically aware and often majority-Black population, yet historically denied full representation and control over its own affairs. This contradiction has been a central catalyst in the Black freedom struggle in the District—where political activism and the push for voting rights and self-governance have always carried deeper stakes, intimately connected to emancipation’s unfinished business.

After the Civil War, Washington’s Black residents—many of them formerly enslaved or descendants of enslaved people—played an outsized role in shaping the political terrain of Reconstruction. They built political clubs, ran candidates for local office when permitted, and participated in lobbying efforts to influence Congress, which holds exclusive authority over D.C.’s affairs under the U.S. Constitution. Despite the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing Black men the right to vote, Congress revoked local voting rights for D.C. residents in 1874, ending home rule for nearly a century. This disenfranchisement, driven by racism and fear of Black political power, made Washington the only U.S. city where American citizens could not vote for their own mayor or city council—effectively maintaining a colonial-style governance over a predominantly Black city.

The struggle for home rule and statehood has thus never been merely a constitutional curiosity or bureaucratic technicality. For generations of Black Washingtonians, it has been a fight for autonomy, dignity, and the right to shape their own lives in the face of a federal government that ruled their streets but denied their voices. Activists such as Julius Hobson, a mathematician, educator, and civil rights organizer, connected the dots between local disenfranchisement and national racial oppression. In the 1960s and 70s, Hobson led marches, lawsuits, and civil disobedience campaigns to expose inequality in schools, public services, and housing, and to demand full civil rights for D.C. residents.

The D.C. statehood movement also became a vehicle for broader liberation ideologies. Marion Barry, the civil rights veteran and four-term mayor, helped crystallize Black political power in the 1970s and 1980s through a politics of economic justice, anti-racist governance, and grassroots empowerment. While his administration was complex and controversial, Barry’s tenure represented a turning point in Black control over municipal structures that had once excluded them. His earlier involvement with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and his later efforts to expand youth employment, public housing, and minority contracting programs, positioned him as both a symbol and a facilitator of Black political strength in the nation’s capital.

Still, D.C.’s political power remained limited. Its residents could vote for President only after the passage of the 23rd Amendment in 1961, and it wasn’t until 1973 that Congress passed the Home Rule Act, allowing D.C. to elect its own mayor and council. But Congress retained veto power over local legislation and budgetary decisions—meaning that even elected Black leadership in D.C. operated under constraints rarely imposed on majority-white jurisdictions.

This structural inequality fueled ongoing protests and legal strategies into the 21st century. The push for D.C. statehood became a centerpiece of local Black activism, with organizations such as Stand Up! for Democracy and the D.C. Statehood Green Party advocating not only for formal representation in Congress but for a moral reckoning with centuries of political suppression. The 2020 racial justice uprisings, following the murder of George Floyd, reignited attention to D.C.’s unique status, as militarized federal forces cracked down on demonstrators near the White House—despite the city’s elected leaders having no control over those deployments.

In this context, statehood is more than a slogan. For Black Washingtonians, it is a demand rooted in the lived memory of slavery, racial disenfranchisement, and persistent economic exploitation. It reflects the historical arc from emancipation to civil rights to modern self-determination—an unbroken line of struggle against racialized governance.

Washington, D.C.'s fight for political justice is thus inseparable from its Black history. The city’s role as a crucible of American power has never insulated its Black residents from the country’s racial contradictions. Instead, it has made their resistance more visible, more urgent, and more symbolic. From the earliest Black petitioners of the Reconstruction era to present-day advocates demanding full rights of citizenship, the people of Washington, D.C., have fought not just for a vote but for the validation of their humanity in the heart of the republic.

Economic resistance has always been an indispensable pillar of Black survival in the United States, and nowhere is this more evident than in the evolution of Washington, D.C.'s Black-owned businesses. From the moment freedom was declared, formerly enslaved people in the District sought not just political rights but the economic autonomy that slavery had long denied them. The freed Black population in Washington rapidly organized systems of mutual support: they formed fraternal societies, burial aid organizations, credit cooperatives, and independent businesses that provided goods and services to their own community when white-owned institutions either refused or exploited them. Economic justice in the District was never a luxury—it was a means of protecting dignity, feeding families, and ensuring collective advancement.

In the years following the Civil War, as thousands of newly freed people poured into D.C. seeking refuge and opportunity, the city became a hub for enterprising Black residents determined to create lives beyond white dependency. Many began as laborers, laundresses, or domestic workers, but soon a rising class of Black artisans, barbers, seamstresses, caterers, and real estate agents emerged. These professions were not accidental. They represented areas where Black workers could bypass white control by serving the Black community or developing skill-based niches the dominant economy needed but failed to formally integrate.

One of the earliest and most well-known examples of Black business development in D.C. was the rise of the Black catering industry. In the 19th century, before restaurants became widespread, formal dining for political elites and the wealthy was conducted through catering. Black caterers in D.C., like Henry Johnson and later the internationally known John T. Cook, established reputations for excellence. Their businesses were not only profitable but provided employment for dozens of others in the community and allowed them to build wealth, purchase homes, and support Black institutions such as schools and churches.

As Jim Crow discrimination hardened in the early 20th century, Black D.C. residents responded by building their own economic infrastructure. The creation of the Industrial Savings Bank in 1913, spearheaded by Black attorney and entrepreneur John Whitelaw Lewis, exemplified this drive toward economic sovereignty. It offered loans and savings options to Black customers who were routinely denied access to white financial institutions. Similarly, Black insurance companies, funeral homes, and benevolent societies flourished, especially in the U Street corridor—once known as “Black Broadway.”

U Street was more than an entertainment destination. It was a comprehensive Black economic ecosystem. From nightclubs and theaters to bookstores, restaurants, law offices, and medical clinics, it offered services that were professional, community-oriented, and culturally affirming. Business owners reinvested their earnings into their neighborhoods, funded scholarship drives, donated to civil rights causes, and provided job opportunities to young people who would otherwise be shut out of the mainstream economy.

This period also saw the emergence of Black women as major economic forces in Washington, D.C. Figures like Mary Church Terrell were not only educators and activists but also staunch advocates of Black women’s financial independence. Organizations like the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), headquartered in D.C., promoted economic literacy, cooperative savings clubs, and business ownership among women. In doing so, they challenged both racism and patriarchy.

Despite this resilience, the forces of white supremacy never relented. Black businesses were targeted by racist city planning decisions, redlining, and the deliberate undermining of D.C.'s Black economic zones. Urban renewal projects in the mid-20th century devastated historically Black neighborhoods under the guise of modernization. Entire business districts were destroyed, and Black entrepreneurs displaced, often without fair compensation. These efforts echoed the spatial violence of slavery: dislocating Black people from their communities and destroying their intergenerational wealth.

In the late 20th century, even as some forms of overt racial exclusion receded, new economic challenges emerged. The decline in federal jobs and the outsourcing of middle-class employment under neoliberal policies hit Black Washingtonians especially hard. Gentrification, rapidly accelerating in the early 2000s, pushed many long-standing residents and small business owners out of neighborhoods they had nurtured for generations. The explosion of white-owned coffee shops, condo developments, and boutique retailers in historic Black neighborhoods was often built quite literally on top of what had been thriving Black commercial spaces.