Tennessee’s geographic positioning as a borderland between the Deep South and the Upper South further defined its complex, violent, and profit-driven system of human bondage. This complexity would echo across centuries, not only in the memory and testimony of those who suffered under slavery but also in the legacies that persist in institutions, land ownership, corporate wealth, and ongoing racial disparities.

When settlers from North Carolina and Virginia began migrating into what would become Tennessee in the mid-to-late 18th century, they brought enslaved Africans with them to clear land, grow crops, tend livestock, build homes, and labor in domestic roles. These enslaved individuals were viewed as property from the outset—investments that increased the economic worth of their white owners and enabled the rapid growth of early settlements like Fort Nashborough (later Nashville), Knoxville, and Jonesborough. Unlike other frontier settlements that were slow to adopt slavery, Tennessee’s adoption of slavery was immediate and systematic, indicating the high value placed on enslaved labor even in its wilderness days. Wealthy families brought not just one or two enslaved people but sometimes dozens, building estates that depended upon human bondage from their inception.

The Tennessee state constitution of 1796, adopted the same year Tennessee achieved statehood, acknowledged and protected slavery. Article 1, Section 1 provided for the security of property rights, and in the legal framework of the time, enslaved people were legally designated as property. The slave codes of Tennessee were rigorous and brutal, forbidding the enslaved from learning to read and write, severely punishing runaways, and mandating patrol systems to hunt down any Black person who dared to move freely. Though slavery in Tennessee may have initially seemed milder in rhetoric than in the Deep South, the day-to-day reality of bondage—beatings, forced separation of families, long work hours, sexual violence, and denial of autonomy—was equally cruel.

The slave economy in Tennessee was not confined to large plantations. While the western part of the state, particularly in counties like Shelby and Fayette near Memphis, resembled the cotton-rich Deep South with its large slave populations and sprawling plantations, the central and eastern regions adapted slavery to smaller farms, industries, and mines.

In East Tennessee, where mountainous terrain made plantation agriculture difficult, enslaved people were rented out for iron manufacturing, saltpeter mining, road construction, and various skilled labor roles. This widespread integration of slavery into every facet of the economy gave rise to a regional version of the slavery industrial complex—an ecosystem where enslaved labor was used not just in the fields but in manufacturing, transportation, mining, and early banking.

The slavery industrial complex in Tennessee was made up of networks of traders, investors, farmers, manufacturers, and financial institutions, all working in tandem to profit from slavery. Enslaved people were mortgaged, insured, and counted among the assets in bank ledgers. Slave markets thrived in cities like Nashville and Memphis, where auction blocks stood prominently and publicly.

Slave traders like Isaac Franklin and John Armfield, who became some of the wealthiest men in the country, operated out of Tennessee and extended their networks across the South, funneling thousands of enslaved people from Virginia and Tennessee to Louisiana and Mississippi. These operations were vast and intricately coordinated, helping to enrich both individual traders and Tennessee’s growing financial sector. Franklin’s estate alone funded future institutions that are today embedded in Tennessee’s elite economic class.

The internal slave trade in Tennessee was also bolstered by state-supported infrastructure projects. The building of railroads such as the Nashville and Chattanooga line was made possible by enslaved labor, sometimes directly and often indirectly by the economic surpluses created from slavery. Enslaved men laid track, transported materials, and built embankments and trestles, often under grueling and unsafe conditions. Tennessee’s roads, levees, canals, and civic buildings were in large part made possible by enslaved workers whose labor was either owned outright or rented by contractors and municipal governments.

The migration of enslaved people within Tennessee was dictated by market needs and family separations. Nashville, centrally located and connected to other markets via rivers and roads, became a key hub for the domestic slave trade. Families were regularly torn apart and sold downriver to Mississippi or Louisiana, and children as young as five or six were sold individually. Many enslaved people in East Tennessee were forced westward as white planters consolidated holdings in more fertile western counties, driven by the profitability of cotton. These internal migrations left deep psychological scars among the enslaved population, embedding intergenerational trauma still felt in descendant communities today.

Even as slavery flourished, resistance never ceased. There were hundreds of documented runaway cases, many of whom tried to escape through the rugged hills of East Tennessee into the free states north of the Ohio River. In that same region, where slavery was less dominant, there was also a higher rate of anti-slavery sentiment. A small but committed abolitionist movement took hold, especially among white Quakers and free Black communities. Some of the earliest anti-slavery newspapers in the South originated in Tennessee, and Underground Railroad activity, though heavily repressed, was present.

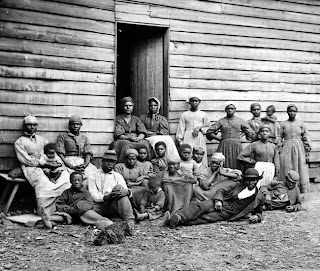

Black Tennesseans—enslaved and free—contributed to a cultural and spiritual identity rooted in resistance and endurance. Enslaved people developed sophisticated oral traditions, religious practices, and musical expressions that sustained them through brutality. Their narratives, preserved through interviews and autobiographies, provide a searing window into the Tennessee slave experience.

The narrative of William Wells Brown, although he escaped from Kentucky, includes harrowing descriptions of his time enslaved in Tennessee. The 1930s Works Progress Administration (WPA) Slave Narratives also include the testimony of former Tennessee slaves, whose memories bear witness to the horrors of child slavery, backbreaking field work, and the omnipresence of white violence. These narratives also reflect pride in endurance, dignity in faith, and a profound longing for justice.

Following the Civil War, Tennessee was the first Confederate state readmitted to the Union in 1866, having nominally accepted the abolition of slavery. However, emancipation was not the end of bondage for Black Tennesseans. The transition from slavery to freedom was riddled with false promises, economic exploitation, and racial terror. Many formerly enslaved people were forced into sharecropping and tenant farming—economic systems that replicated the conditions of slavery under a new name. Without access to land, tools, or capital, they remained beholden to white landowners who manipulated ledgers and withheld payment to keep them in cycles of debt. The Freedmen’s Bureau, tasked with assisting newly freed people, opened offices across Tennessee in cities like Memphis, Nashville, and Chattanooga. The Bureau helped to establish schools, record marriages, protect labor contracts, and provide limited legal advocacy. However, the Bureau faced intense opposition from white Tennesseans and was chronically underfunded. In Memphis, the Bureau’s presence could not prevent the 1866 Memphis Massacre, where white mobs, including police and former Confederates, attacked Black neighborhoods, killing more than 40 people and burning homes, churches, and schools.

Despite violent repression, Black Tennesseans organized for education, political participation, and land ownership. Freedmen’s schools sprung up with support from the Bureau and northern missionary societies. Fisk University was founded in 1866 to provide higher education to formerly enslaved people and became a beacon of Black excellence. The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a choral group formed at the university, traveled the world to raise funds and elevate the cultural heritage of African Americans, rooted in the spirituals born in slavery.

Other Tennessee colleges also have historical ties to slavery. Vanderbilt University, named after Cornelius Vanderbilt who made his fortune partly through steamboats operated with enslaved labor, has publicly acknowledged its complicated legacy. The University of Tennessee benefited from funds and land tied to slavery-era wealth. Many of these institutions have begun examining their ties to slavery through historical commissions and reparative scholarship, but their endowments, land grants, and physical structures remain symbols of accumulated wealth built in part on human suffering.

Corporate beneficiaries of slavery in Tennessee are also numerous. Banks like First Horizon and insurance companies with 19th-century roots in slave policies and property protection are implicated in the legacy of slave-based commerce. Steamboat companies, railroads, and textile mills, some of which evolved into modern industrial entities, made their profits through direct or indirect dependence on enslaved labor. Though rebranded and often merged into conglomerates, their founding assets often originated in antebellum slave-based economies.

Notable Tennessee abolitionists include figures like Elihu Embree, who published one of the nation’s earliest abolitionist newspapers, The Emancipator, in Jonesborough. His bold stance in a slaveholding state placed him at great personal risk. Others, including Frances Wright, who attempted to establish a utopian, racially-integrated settlement near Memphis in the 1820s, faced bitter opposition. Despite their failures, these figures helped to keep the moral outrage against slavery alive within the state.

The experiences of formerly enslaved Black Tennesseans in the years following emancipation represented both a continuation of oppression and a testament to resilience and determination. The years of Reconstruction, though brief, were a moment when Black Tennesseans organized to redefine citizenship, justice, and their place within a society that had profited from their exploitation. Freedmen exercised their newly acquired rights to vote, run for office, organize schools, build churches, and form fraternal and mutual aid societies.

Political participation surged during this time. Black legislators were elected to the Tennessee General Assembly, and community leaders emerged from the ranks of the formerly enslaved to provide leadership in schools, congregations, and new civic organizations.

The postbellum period was also a time of intense backlash. As formerly enslaved people attempted to assert their rights to land, wages, education, and bodily autonomy, white supremacist violence escalated. Tennessee was the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan in 1866, founded in Pulaski by Confederate veterans determined to undermine Black advancement and restore white dominance.

The Klan’s reign of terror included beatings, lynchings, arson, and intimidation, with the explicit goal of dismantling the political, economic, and educational gains made by African Americans. Schools established by the Freedmen’s Bureau or by Black communities were frequent targets of arson. Teachers were attacked. Churches and fraternal halls were burned. Political leaders were assassinated or threatened into silence.

Despite this, many African Americans in Tennessee remained determined to forge new futures. The establishment of Black churches such as the African Methodist Episcopal Church, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (now the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church), and Black Baptist congregations provided spiritual refuge, educational training, and a political platform. Ministers often served as community organizers, orators, and advocates for civil rights. They became central figures in every Black Tennessee community, helping to build literacy, self-governance, and resistance strategies under hostile conditions.

The period from the 1870s through the early 20th century was marked by the emergence of Jim Crow laws, Black Codes, and other legal strategies that systematically excluded Black Tennesseans from power. Segregation was formalized in schools, public accommodations, transportation, and voting systems. Grandfather clauses, literacy tests, and poll taxes were implemented to disenfranchise Black voters.

In the state that had been first to ratify the 14th Amendment, the promise of full citizenship was swiftly curtailed. Landownership among Black families remained low, as economic pressure, discrimination in credit and banking, and land theft forced many into sharecropping arrangements. These arrangements were often exploitative and functioned as a continuation of slavery by another name.

The convict lease system became another brutal extension of slavery in Tennessee. Enacted soon after the Civil War, it allowed incarcerated people, most of whom were Black, to be leased to private businesses and plantation owners to work under horrific conditions. Arrests were often racially targeted, based on minor or fabricated infractions, such as vagrancy, loitering, or “insulting white women.”

The state profited by leasing prisoners to coal mines, railroads, lumber companies, and other industries. Tennessee’s Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary and other prison labor operations were notorious for extreme brutality, unsanitary conditions, and high mortality rates. Black prisoners were beaten, starved, and overworked, with little to no access to legal recourse.

Among the most infamous incidents of racial terror during this era was the lynching of Ell Persons in 1917 in Memphis. Accused without trial of assaulting a white girl, Persons was burned alive before a crowd of thousands that included families with children. Local newspapers had advertised the event in advance. No one was punished. This lynching galvanized Black organizers in Memphis to form the local branch of the NAACP.

They began to demand federal anti-lynching laws, greater legal protections, and social justice reforms. The struggle against lynching continued into the mid-20th century, as hundreds of African Americans in Tennessee were publicly murdered without consequences for the perpetrators. These acts of terror were designed to maintain white supremacy and economic domination.

At the same time, a cultural renaissance was emerging among Black Tennesseans. In the early 20th century, Memphis, Nashville, and Chattanooga became centers of Black enterprise, culture, and education. The Beale Street district in Memphis was a hub of Black-owned businesses, music clubs, professional offices, and civic organizations. Booker T. Washington High School, the first accredited high school for Black students in Memphis, graduated generations of civic and cultural leaders. Fisk University in Nashville continued to thrive, producing Black intellectuals, artists, and civil rights advocates. The school attracted nationally and internationally renowned educators and thinkers. In 1926, W.E.B. Du Bois spoke at the school, linking its mission to the larger struggle for racial equality and liberation.

Meanwhile, Black labor in Tennessee’s cities and rural areas remained crucial to the state’s economy. From tobacco warehouses to railroads, steel foundries, textile mills, and shipping companies, Black workers labored underpaid, overworked, and often excluded from labor unions. Despite barriers, Black workers in Tennessee organized collectively. In Memphis, the rise of the Black labor movement laid the foundation for later activism, including the formation of Black-led unions and civil rights labor coalitions. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, for example, had an active presence in Tennessee. As one of the most successful Black labor organizations in the country, it helped to advance not only labor rights but also racial justice in the workplace and beyond.

By the mid-20th century, Tennessee had become a key battleground in the struggle for civil rights. The legacies of slavery and Jim Crow fueled a new generation of freedom fighters who challenged segregation, inequality, and systemic racism. The Highlander Folk School in Monteagle served as a training center for civil rights organizers, including Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King Jr., and Septima Clark. Founded in the 1930s, Highlander helped to develop nonviolent resistance strategies, promote interracial education, and support the labor movement. Despite repeated attacks by the state, Highlander remained a beacon of radical education and civil disobedience.

In Nashville, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed in large part by students from Fisk University, Tennessee State University, and American Baptist College. Leaders like John Lewis, Diane Nash, James Lawson, and Bernard Lafayette organized sit-ins, freedom rides, and voter registration drives. The Nashville Sit-Ins of 1960 were among the most well-coordinated and successful in the South. Young Black activists occupied segregated lunch counters, enduring violence, arrest, and harassment with unwavering commitment to nonviolence. Their discipline and courage shook the foundations of Jim Crow and forced the city to desegregate public accommodations.

In Memphis, the garbage workers’ strike of 1968 was one of the most important labor and civil rights actions in American history. The strike began after the deaths of Echol Cole and Robert Walker, two Black sanitation workers crushed to death in a malfunctioning garbage truck. Their deaths highlighted the inhumane working conditions faced by Black municipal workers. Over 1,300 Black sanitation workers went on strike, demanding better wages, safer working conditions, and union recognition.

Their rallying cry—“I AM A MAN”—was a direct challenge to centuries of dehumanization rooted in slavery. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. traveled to Memphis to support the strike, delivering his famous “Mountaintop” speech the night before he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel. His death in Memphis, at the hands of a white supremacist, underscored the deadly resistance to Black dignity and power.

Despite these sacrifices, economic disparity rooted in the legacies of slavery persisted. Redlining, predatory lending, school segregation, and employment discrimination continued to define the Black experience in Tennessee’s cities and rural communities. Generations of African Americans were denied access to the intergenerational wealth enjoyed by white families who had benefited from slavery, Jim Crow, and publicly-funded segregation. Corporate expansion in Tennessee, particularly in the finance, insurance, and higher education sectors, grew directly out of systems built during the slave era.

Many of Tennessee’s largest companies have benefited from this legacy. Cotton traders, textile companies, banks, and railroads that flourished during the 19th century evolved into 20th-century conglomerates. The successors of these firms continue to operate in Tennessee, their foundations laid by the unpaid labor of enslaved people. Similarly, universities like the University of the South (Sewanee), which was founded by Southern bishops in the 1850s with explicit ties to slavery and the Confederacy, have only recently begun to acknowledge their histories of exploitation and racial exclusion. Public and private colleges across Tennessee used funds from slavery-enriched donors, built infrastructure with enslaved labor or convict leasing, and excluded Black students for more than a century.

The reckoning with this past is ongoing. In recent years, Tennessee scholars, activists, and descendants of the enslaved have demanded reparations, historical truth-telling, and institutional accountability. Projects to document slave cemeteries, rename buildings, and revise educational standards have emerged, though often in the face of political resistance. Tennessee’s official curriculum on slavery has historically been minimal, sanitized, or distorted. Grassroots efforts, such as those by the Tennessee African American Historical Group, seek to change this by publishing oral histories, erecting markers, and developing community-based educational tools.

Slave narratives remain a central piece of this work. The stories of enslaved Tennesseans, preserved in archives and passed down through generations, speak of both unspeakable pain and extraordinary courage. Stories like that of Matilda Jackson, who was forced to leave her children when sold in Nashville; or Samuel Johnson, who escaped a slave trader and later returned to liberate his family; or Hannah Hill, who recorded songs sung in the cotton fields outside of Memphis—each testify to the humanity, resistance, and resilience of those who endured slavery in Tennessee.

These stories also confront today’s Tennessee with uncomfortable truths. The disparities in wealth, education, incarceration, and health outcomes that affect Black communities in Tennessee are not accidental. They are the predictable outcomes of systems built during slavery and reconfigured in each generation to preserve white dominance. Every step toward justice—be it land restitution, educational equity, or corporate reparations—must begin with a full and unflinching confrontation with this legacy.

To understand the long arc of slavery’s influence in Tennessee, one must look not only to its formal institutions and industries, but to the layered and generational impact on the state’s demographic and cultural development. The social hierarchy imposed by slavery set rigid boundaries that were codified through law and custom, and those boundaries did not disappear with emancipation—they simply evolved. The descendants of enslaved Tennesseans carried the burden of exclusion through new forms of racial subjugation: separate and unequal schools, under-resourced communities, blocked access to housing and employment, and a justice system designed to perpetuate mass control rather than equal protection.

In the years following the Great Migration—when thousands of Black families left Tennessee for northern and midwestern cities like Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland—those who remained faced the dual pressures of racial violence and economic stagnation. Yet even within this reality, they built networks of mutual support and cultural innovation. Black neighborhoods in cities like Nashville and Memphis became epicenters of Black expression, education, and resistance. Jefferson Street in Nashville, once home to thriving Black-owned businesses, jazz clubs, barber shops, and community organizations, emerged as a symbol of Black pride. It was the beating heart of Nashville’s Black community, connecting students from historically Black colleges like Fisk, Meharry Medical College, and Tennessee State University to the broader struggle for social uplift.

Meharry Medical College in particular deserves mention for its historic role in producing Black physicians and medical professionals at a time when nearly every medical school in the country was closed to African Americans. Founded in 1876 with funds from a white abolitionist donor, Meharry not only trained Black doctors but actively sent graduates back into rural and underserved communities across the South, where medical care for African Americans was nearly non-existent. These physicians were not only healers but also community leaders and civil rights advocates. In many small towns across Tennessee, the presence of a Meharry-trained doctor meant the difference between life and death, dignity and neglect.

But while institutions like Meharry fought to serve Black Tennesseans, others in the state continued to profit from their exclusion. Public and private hospitals across Tennessee remained segregated well into the 20th century, and even after formal integration, many denied Black patients the same quality of care offered to whites. The structures built by slavery—of systemic denial and devaluation of Black life—persisted in subtle but deadly ways. These disparities are visible today in Tennessee’s maternal mortality rates, life expectancy gaps, and health care access inequalities, all of which disproportionately affect Black communities.

The same patterns are evident in education. Black schools in Tennessee during segregation were chronically underfunded, overcrowded, and understaffed. Teachers often received lower pay than their white counterparts, even as they worked longer hours and taught in inferior facilities. Despite this, these educators were fiercely committed to their students and communities. Many came from local Black colleges and brought a deep sense of purpose and activism to their roles. These schools were more than classrooms—they were centers of organizing, cultural preservation, and political training. When Brown v. Board of Education mandated school desegregation in 1954, Tennessee, like many Southern states, responded with resistance. Token integration was followed by white flight, the closing of Black schools, and the firing of Black teachers.

The city of Clinton, Tennessee, in Anderson County, became the site of the first court-ordered integration of a public high school in the South in 1956. Twelve Black students known as the “Clinton 12” integrated Clinton High School under intense hostility, harassment, and threat of violence. One year later, the school was bombed and reduced to rubble. The students were forced to attend classes in makeshift buildings while white resistance groups organized to prevent future integration. Such incidents illustrate the cost of progress in a state that had once pioneered Reconstruction-era reforms only to recoil from them in the 20th century.

Meanwhile, in higher education, historically white institutions continued to marginalize Black Tennesseans. Admission remained highly restricted until the late 1960s, and even after formal desegregation, Black students were often isolated, unsupported, and targeted by discrimination. The University of Tennessee system, among others, admitted its first Black undergraduates only under federal pressure and legal action. Today, although progress has been made, Black student enrollment, faculty hiring, and cultural inclusion remain ongoing challenges at Tennessee’s flagship institutions. Many of these schools still carry the legacies of slavery in their architecture, traditions, donor names, and financial foundations.

Tennessee’s corporate sector also bears the imprint of slavery’s legacy. Cotton remained a dominant economic force in West Tennessee well into the 20th century, even after slavery was abolished. Sharecropping and tenant farming, which replaced slavery in name only, enabled white landowners and textile manufacturers to continue extracting wealth from Black labor without providing fair compensation or upward mobility. Companies that processed cotton, manufactured garments, and exported goods built empires on this exploitative system. Memphis, known as the “Cotton Capital” of the South, hosted major cotton exchanges and shipping operations that were direct descendants of antebellum slave-based commerce. The economic foundation of the city’s port and shipping industry cannot be separated from its origins in enslaved labor and the trade in human beings.

Many of these same companies evolved into banks, insurance firms, and logistics corporations that dominate Tennessee’s economic landscape today. Some of the original investments made by slaveholders were later folded into trust funds, property holdings, and early corporate charters. The cumulative wealth of white families and institutions grew steadily over generations, while Black families were repeatedly denied access to the capital needed to build their own economic base. Even in the 21st century, Black Tennesseans are more likely to be denied mortgages, offered higher interest rates, and excluded from property development opportunities. The racial wealth gap in Tennessee remains among the highest in the nation, a testament to the long shadow cast by slavery.

In rural areas of the state, particularly in West Tennessee, the legacy of slavery also shapes patterns of land ownership. While formerly enslaved people sought to purchase land during Reconstruction, they were often driven off through legal trickery, violence, and economic coercion. Deeds were forged, taxes were inflated, and sheriffs were used to seize property. In places like Haywood, Hardeman, and Lauderdale counties, entire Black communities were uprooted or economically gutted. The land they once farmed was consolidated under white control, and many Black families became permanent renters or left the state entirely. The disappearance of Black land ownership has had long-term effects not only on wealth accumulation but on political power, environmental justice, and community stability.

These historical forces have also influenced patterns of incarceration in Tennessee. As in other Southern states, the over-policing and criminalization of Black life has its roots in slave patrols and Black Codes. In the decades following emancipation, Tennessee built a penal system that disproportionately targeted Black men, women, and children. From the convict lease system to modern private prisons, the pattern has remained the same: exploit Black labor for state or corporate profit under the guise of criminal justice. Today, Tennessee maintains one of the highest incarceration rates in the country, with Black people incarcerated at five times the rate of white people. This system removes fathers from families, erodes civic engagement, and reproduces economic inequality on a mass scale.

Many of the state’s most notorious prisons, including Riverbend, Turney Center, and West Tennessee State Penitentiary, are located near former plantations or along the same transportation routes once used in the domestic slave trade. These institutions often contract labor from prisoners to corporations for pennies an hour, a practice that scholars and activists describe as modern-day slavery. The 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, which abolished slavery except as punishment for a crime, remains an active legal framework supporting such exploitation. Tennessee’s continued reliance on prison labor as a means of economic development echoes its antebellum dependence on enslaved workers.

And yet, despite these structures of oppression, Black Tennesseans have continuously fought back. They have built powerful churches, educational institutions, labor organizations, and civic groups. They have raised generations of freedom fighters—from the anonymous to the iconic. One such figure is Ida B. Wells, born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, but whose activism flourished in Memphis. As a journalist, Wells exposed the truth about lynching, demanding justice in a state that preferred silence. After her newspaper office was destroyed by a white mob, she continued her campaign nationally and internationally, forcing the world to confront Tennessee’s racial terror. Her work laid the foundation for investigative journalism and Black feminist organizing that would follow in her wake.

Later generations of Tennessee freedom fighters built upon her legacy. Z. Alexander Looby, a civil rights attorney in Nashville, defended students arrested during the sit-ins and helped desegregate schools through the courts. His home was bombed in retaliation, but he never ceased his work. The Reverend Kelly Miller Smith Sr., another pivotal figure in Nashville’s civil rights movement, mentored a young John Lewis and served as a moral compass for the city’s activism. His sermons and organizing forged bonds between the pulpit and the picket line. Diane Nash, a brilliant strategist and activist from Fisk University, became a national leader through her fearless work with SNCC and the Freedom Rides. Her clarity and moral authority challenged presidents and governors alike.

These leaders did not act alone. They were part of larger networks of students, clergy, factory workers, domestic workers, and ordinary citizens who risked their lives to dismantle the scaffolding of white supremacy built on slavery’s foundation. Their courage echoes today in every protest against police violence, every demand for fair housing, every push for educational justice. They remind us that the story of slavery in Tennessee is not just a story of bondage—it is a story of resistance, renewal, and righteous struggle.

As the state of Tennessee moves deeper into the 21st century, questions of memory, responsibility, and repair remain unresolved. Monuments to Confederate leaders still stand in public spaces. Public school curricula continue to minimize slavery’s central role in American and Tennessee history. Gentrification displaces Black communities, while historical Black neighborhoods are renamed, rezoned, or erased. Yet Black Tennesseans persist. They organize historical tours, preserve ancestral cemeteries, form mutual aid collectives, launch political campaigns, and demand that the full story be told. The fight for justice is ongoing—not only to remember the past but to transform the future.

In order to truly reckon with the consequences of slavery in Tennessee, one must consider the geographic specificity of its impact across different regions of the state. Each part of Tennessee—East, Middle, and West—developed distinct relationships to slavery, and those distinctions continue to shape the political, cultural, and economic landscapes of the state today. East Tennessee, with its mountainous terrain and smaller farms, had fewer enslaved people overall but was not free of slavery. Some of the region's iron foundries, saltpeter mines, and lumber operations relied on enslaved labor to meet industrial demands.

In Middle Tennessee, where the landscape favored agriculture and commerce, cities like Nashville became central to the slave trade and to the enslaved labor economy. Nashville's growth as a transportation and commercial hub was largely made possible through slave labor on railroads, in warehouses, on the docks, and in domestic service. In West Tennessee, especially around Memphis, plantation agriculture flourished. The fertility of the soil along the Mississippi River made the region ideal for cotton cultivation, which was fully dependent on slave labor and made local planters extremely wealthy. These geographic patterns not only affected the type of labor enslaved people performed but also the kinds of resistance and survival strategies they employed.

Slaveholders in Tennessee ranged from the wealthy planter elites who owned dozens or even hundreds of enslaved people to middling farmers and merchants who might have owned a single enslaved person to help with household chores, labor in a small field, or act as an apprentice. In cities, enslaved people worked as blacksmiths, seamstresses, butchers, laundresses, cooks, carpenters, and coachmen. Many were hired out by their owners, working for wages that went directly to the enslaver. In some cases, enslaved people were able to negotiate partial retainment of their earnings, but this was exceptional and always subject to revocation. Some of these urban slaves had slightly more mobility, which they used to build underground networks, forge false papers, or plan escapes.

Slave resistance took many forms in Tennessee, from outright rebellion to more subtle forms of sabotage, evasion, and cultural preservation. Enslaved people broke tools, feigned illness, worked slowly, and manipulated their assigned roles to maintain a semblance of control over their lives. Religious gatherings often served as spaces of coded communication and cultural endurance. “Invisible churches” and brush arbor meetings allowed enslaved Tennesseans to practice their spirituality outside the surveillance of slaveowners, where Christian doctrine was fused with African traditions and reinterpreted through the lens of deliverance and freedom. Songs, prayers, and testimonies became the foundation of Black religious life in Tennessee, carrying forward the belief in liberation even when earthly evidence seemed absent.

Runaway slave ads printed in Tennessee newspapers offer a disturbing window into the widespread attempt to deny humanity to Black people while simultaneously recognizing their intelligence, agency, and courage. These ads often described in precise detail the appearance, speech, mannerisms, and skills of the escaped person. Many noted that the runaway “can read and write,” was “clever and sly,” or “likely to attempt passage on a steamboat.” These notices also reveal the sophisticated strategies employed by the enslaved to forge free papers, travel in disguise, or rely on allies in towns and cities across the state. While escape from slavery was dangerous and rare, its persistent presence signaled the deep resistance enslaved Tennesseans maintained against their condition.

Some of Tennessee's most remarkable freedom seekers became legendary figures. One such individual was Eliza Winston, who escaped from her owner while traveling through Memphis and successfully secured her freedom with the help of local abolitionists. Another was William Shackelford, who escaped slavery and joined the Union Army, later returning to Tennessee to assist others in securing their liberation. While many of these stories were suppressed or forgotten by official history, they have been reclaimed by scholars, family descendants, and community historians determined to honor the true breadth of Black resistance.

With the arrival of Union troops in Tennessee during the Civil War, especially after the fall of Nashville in 1862, thousands of enslaved people fled plantations and towns to seek refuge behind Union lines. Many were immediately put to work by the Union army as laborers, cooks, laundresses, and teamsters. Some enlisted in the United States Colored Troops (USCT), with Tennessee ultimately providing over 20,000 Black men to the Union cause. These men fought in critical battles and provided labor essential to Union military campaigns. They did so while still being paid less than white soldiers, and in some cases, without their families being freed. Despite this, their contributions helped to shift the war from a battle to preserve the Union into a struggle for emancipation.

The post-war period in Tennessee was complicated by the state’s unique position as the first former Confederate state to rejoin the Union. While the Radicals in the Tennessee legislature passed laws granting limited civil rights to freedmen and supported the development of the Freedmen’s Bureau, these measures were fiercely opposed by white supremacists. The state’s early efforts at Reconstruction were undermined by political violence, racial terror, and federal inaction. As Reconstruction faded, Jim Crow laws hardened racial divisions and laid the foundation for white supremacy’s resurgence in all areas of life.

This racial order was maintained not just through violence and policy, but through culture and collective memory. White Tennesseeans enshrined a narrative of the “Lost Cause” that depicted the Confederacy as noble and benign, portraying slavery as a benevolent system and Black people as loyal, inferior, and dependent. This myth was taught in schools, displayed in public monuments, and repeated in religious sermons and local histories. It functioned to erase the brutality of slavery and to justify the continued subjugation of Black people. For generations, children in Tennessee learned more about Confederate generals than about enslaved freedom seekers or Black civic leaders. This distortion of history was not incidental—it was foundational.

The educational neglect of slavery’s true legacy created a moral vacuum that persisted into the modern era. Public school textbooks omitted the violence of slavery or cast it in euphemistic terms. Museums and heritage sites often focused on antebellum architecture, clothing, and white family lineages without mentioning the enslaved people who built and maintained those estates. Even where slave quarters still stood, they were often framed as rustic features rather than sites of suffering and survival. Only in recent decades have efforts emerged to reframe these spaces, incorporating the voices of the enslaved and confronting visitors with the full truth.

Public historians, educators, and descendants have led the charge to revise this narrative. Institutions like the Tennessee State Museum, the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, and community archives across the state have begun centering the voices and experiences of enslaved and formerly enslaved people. Exhibits now feature oral histories, artifacts, and scholarly research that challenge romanticized versions of Tennessee’s past. Programs in public schools and universities are also evolving, with a growing emphasis on teaching slavery not as a peripheral issue but as central to understanding the state's formation and present inequalities.

Despite these efforts, state politics in Tennessee have often hindered full truth-telling. Legislation restricting how teachers can discuss race, slavery, and systemic injustice in the classroom has been introduced and passed in recent years. This climate of suppression reflects a continued resistance to confronting the uncomfortable truths of history. While the state government sponsors some commemorative efforts, it remains reluctant to support initiatives that include reparative justice or structural change. The resistance to such work stems not only from political conservatism but from the enduring discomfort of a society whose prosperity was built on stolen labor.

Corporate responsibility for slavery's legacy has also been slow and uneven. While some companies with historical ties to slavery—particularly in insurance and finance—have issued statements acknowledging their pasts, few have taken substantial steps toward restitution. Local governments and institutions of higher learning have faced increasing pressure from community groups and students to audit their endowments, reveal the sources of their early capital, and invest in descendant communities. These efforts mirror national movements but remain contentious in Tennessee, where economic and racial hierarchies remain deeply intertwined.

The call for reparations in Tennessee has gained traction in certain municipalities. In Nashville, community organizers have proposed municipal-level reparations that could include housing grants, educational scholarships, and investments in historically Black neighborhoods. In Memphis, advocacy groups have pushed for similar programs. These efforts are not simply about financial compensation—they are about structural transformation. Reparations offer a framework for addressing generational theft, not just individual harm. Yet the idea remains politically polarizing, and no statewide reparations policy has yet been implemented. The work continues, driven by grassroots organizations, faith communities, and cultural workers who understand that true justice must include economic redress.

The cultural memory of slavery in Tennessee lives on in the stories passed from generation to generation. These include not only the pain and horror of bondage but also the strength, ingenuity, and dignity of the enslaved. Black Tennesseans have kept these memories alive through family oral histories, church traditions, commemorative events, and literary production. Writers like Alex Haley, whose family history in Tennessee became the basis for his groundbreaking novel Roots, helped to spark a national conversation about Black ancestry and the enduring impact of slavery. Haley’s work traced a path from Africa to Tennessee plantations to modern-day struggles, emphasizing continuity, identity, and resistance.

These narratives are not simply history—they are fuel for contemporary justice movements. Black Lives Matter activists in Tennessee have invoked the names of enslaved ancestors and freedom fighters as they challenge police brutality, voter suppression, and environmental racism. Community gardens in North Nashville invoke traditions of Black land stewardship. Black student organizations at the University of Tennessee, Vanderbilt, and Middle Tennessee State University continue to demand inclusive curricula, representational justice, and institutional transparency. Their work is part of a long tradition of Black struggle in Tennessee—one that began under the whip and has endured through every form of oppression.

As we approach the final segment of this spotlight, we turn to the question of legacy—not only what has been inherited, but what must be done. The history of slavery in Tennessee is not a closed chapter. It is a living history that continues to shape the health, wealth, power, and hope of millions of people. To acknowledge this history fully is not an act of shame—it is an act of courage. And it is the only foundation on which a just future can be built.

The story of slavery in Tennessee is not merely a tale from the past—it is a mirror held up to the present and a challenge directed toward the future. Every field once tilled by enslaved hands, every courthouse where human property was transacted, every brick laid by forced labor, and every institution that accumulated wealth through bondage stands as a silent witness to a reality that still shapes modern life. Slavery in Tennessee was not an aberration or a footnote. It was central to the development of the state’s wealth, its systems of governance, its corporate emergence, and its social hierarchies. To examine this truth in its totality is not only a moral imperative but a necessary foundation for justice.

Throughout Tennessee’s rural landscapes and urban corridors lie unmarked graves of enslaved people, forgotten quarters behind stately mansions, and once-thriving Black neighborhoods that have been paved over or gentrified. These physical absences represent a historical amnesia that must be actively countered. They are reminders that the legacy of slavery was not simply the years of bondage, but the years of exclusion that followed. The denial of land, education, justice, and wealth—these were all the aftershocks of slavery, and they continue to resonate in contemporary Tennessee.

The educational disparities between Black and white children in Tennessee are not new—they are a continuation of a system that once made it illegal for enslaved people to read. The disproportionate policing and incarceration of Black Tennesseans are not contemporary anomalies—they are rooted in slave patrols and convict leasing. The underrepresentation of Black faculty at Tennessee universities, the racial wealth gap, the displacement of Black residents from urban neighborhoods, the environmental hazards disproportionately affecting Black communities—each of these realities stems directly from a system that commodified Black people and then erased their contributions from the ledger of the state’s development.

There is no county in Tennessee untouched by slavery’s shadow. In Memphis, the former cotton capital of the South, slavery's legacies are evident in both economic geography and social stratification. In Nashville, the very streets trodden by tourists in the heart of downtown were once slave auction routes, and the institutions that now dominate the skyline were built on the backs of enslaved labor. In small towns like Columbia, Jackson, Brownsville, or Greeneville, the stories of enslaved people are embedded in church basements, cemetery plots, courthouse archives, and family oral histories—rarely told publicly, but ever-present to those who choose to listen.

In recent years, descendants of the enslaved in Tennessee have begun to reclaim these narratives in powerful ways. Community groups have organized historical marker campaigns to publicly honor enslaved individuals and their contributions. Universities have formed commissions to investigate the names on their buildings, the sources of their endowments, and the roles that faculty and alumni played in supporting slavery and segregation. Museums and cultural centers have created permanent exhibits that center the voices of the enslaved, including digitized archives of letters, testimonies, and manumission documents. Churches founded by freed people in the 19th century have begun to catalog and publicize their histories, asserting their place as some of the oldest Black institutions in Tennessee.

But this work must go further. Historical truth must lead to reparative action. The harm done by slavery and its legacy in Tennessee was not accidental—it was systematic, targeted, and generational. Redress must be the same. A genuine response to slavery’s impact in Tennessee must include investment in Black communities that have been historically divested from. It must include the return or shared stewardship of land that was seized through coercion, fraud, or racial violence. It must include reparative educational initiatives, including tuition remission for descendants, Black-led curriculum development, and public memorials. It must include political and economic empowerment that recognizes the debt owed to generations of people who built this state without pay, without rights, and without recognition.

In the legislative sphere, Tennessee has the opportunity to lead—not in erasing its past, but in confronting it with honesty. State-sponsored commissions on truth and reconciliation, funded reparations task forces, and curricular reforms in K-12 education can all begin to heal the rupture caused by slavery and its aftermath. Rather than banning the teaching of systemic racism, the state could model what courageous truth-telling looks like. Rather than resisting accountability, institutions could join descendant communities in crafting a future grounded in equity and shared prosperity. Justice does not threaten Tennessee’s future—it secures it.

The descendants of enslaved Tennesseans have never waited for permission to create beauty, to demand dignity, or to build power. From the abolitionist newspapers of East Tennessee to the Civil Rights organizing on Jefferson Street; from the prayers whispered in brush arbor meetings to the anthems sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers; from the lynching protests led by Ida B. Wells to the sit-ins led by Diane Nash; from the sanitation workers proclaiming “I AM A MAN” to the present-day organizers calling for justice in the wake of state violence—the Black people of Tennessee have never accepted slavery or its echoes as natural. They have contested it at every turn. Their resistance is the true moral backbone of the state.

As Tennessee continues to reckon with this history, it must center these voices. Museums, archives, and academic institutions should not merely display stories of the enslaved but should collaborate with their descendants to tell these stories in full, with integrity and reverence. Government officials, business leaders, and educators must be willing to hear uncomfortable truths, to unlearn sanitized versions of the past, and to commit to long-term change.

This is not about guilt—it is about responsibility. The wealth created by slavery has not disappeared. It exists in land, in bank accounts, in institutional endowments, and in the political and social capital accumulated over generations. The poverty, trauma, and disenfranchisement created by slavery have also not disappeared. They exist in neighborhoods stripped of investment, in schools denied funding, in health crises, in mass incarceration, and in the structural inequalities that define modern Tennessee.

Slavery in Tennessee was not an unfortunate relic—it was a deliberate institution designed to generate profit and enforce white supremacy. Its end did not mark the beginning of justice, but the beginning of a new struggle. That struggle continues today. It is visible in the fight to preserve Black historical sites from development, in the push to end discriminatory policing, in the campaign for environmental justice in communities poisoned by proximity to landfills and industry. It is visible in the art, poetry, and scholarship of Black Tennesseans who are telling the truth about this land and the blood that built it.

The path forward is not easy. It demands truth. It demands courage. It demands accountability. But most of all, it demands remembrance. The enslaved men, women, and children who lived and died in Tennessee—who tilled the soil, who bore the blows, who resisted in ways small and large—are not gone. Their descendants live. Their songs endure. Their labor remains the cornerstone of a state that owes them far more than it has yet given. They are not footnotes. They are the foundation.

To reckon with slavery in Tennessee is not to tear down—it is to build. To build a society that honors the truth. A society that sees justice not as a threat, but as an obligation. A society where the full humanity of Black Tennesseans is no longer contested but celebrated. This is the unfinished work of emancipation. This is the real work of remembrance.

And only when that work is done—only when Tennessee looks at every courthouse, every university, every plantation museum, every prison, every company, every ledger, every street name, every state standard, every policy, and every child and says “We remember, we repair, and we will not repeat”—only then can the state truly claim to be free from the chains of its beginning.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

Washington D.C.

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad