The Civil Rights Movement, emerging most visibly in the mid-twentieth century, cannot be understood solely as a campaign for racial justice for African Americans; it is a seminal watershed in the history of the United States, engendering legal, cultural, political, and social reforms whose benefits extend far beyond the Black community. Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and even White Americans have, in diverse ways, been beneficiaries of the profound restructuring of social norms, legal frameworks, and institutional practices initiated by African American activism. In this light, the movement assumes a universalist dimension, wherein the struggle for racial equity constitutes not merely a particularistic endeavor but a paradigmatic assertion of democratic principles that strengthens the moral and civic architecture of the nation as a whole.

The antecedents of the Civil Rights Movement are embedded within centuries of entrenched racial hierarchies that began with the transatlantic slave trade and the codification of slavery within colonial law. The enslavement of Africans in the American colonies established a labor system predicated on coercion, violence, and the systematic denial of agency, creating social, economic, and political structures designed to perpetuate white supremacy.

The moral and philosophical contradictions of a nation founded upon the ideals of liberty and equality while sustaining human bondage catalyzed early antislavery discourses, yet these were often circumscribed by the pervasive power of pro-slavery interests. Even after the formal abolition of slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, African Americans faced the structural legacies of bondage in the form of Black Codes, convict leasing, sharecropping, and systemic disenfranchisement, which entrenched socioeconomic marginalization and maintained the racialized distribution of power.

The Reconstruction era (1865–1877) represents both the apex of early federal intervention in racial justice and the limits of its efficacy. Constitutional amendments—the Fourteenth and Fifteenth—codified principles of citizenship, equal protection, and suffrage, yet their promise was undercut by violent white supremacist insurgencies, the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and the complicity of Northern political actors who gradually abandoned the cause of African American enfranchisement. The subsequent establishment of Jim Crow laws in the South crystallized the racial hierarchies into a legally sanctioned architecture of segregation and subordination.

Public accommodations, education systems, and civic participation were meticulously segregated, while the enforcement of these policies was buttressed by terror and state-sanctioned coercion. African Americans lived under a duality of visibility and erasure: they were indispensable to the economic machinery of the South yet systematically excluded from its political and cultural dominions.

Parallel to these oppressions, African American intellectual and cultural resistance began to take shape, foreshadowing the later Civil Rights Movement. The formation of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 signaled the emergence of organized legal advocacy as a central strategy for racial justice. African American lawyers, journalists, and educators articulated a vision of equality grounded in both constitutional principles and the universalist ideals of human dignity. Landmark legal challenges, including early NAACP suits against segregation in education and public accommodations, laid the groundwork for the jurisprudential victories of the mid-twentieth century. These efforts demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the American legal system as a vehicle for social transformation, presaging the movement’s later reliance on litigation alongside grassroots mobilization.

The eruption of mass African American migration from the rural South to urban centers in the North and West between 1916 and 1970—the Great Migration—profoundly altered the demographic, cultural, and political landscapes of the United States. Cities such as Chicago, Detroit, Oakland, New York, and Los Angeles became crucibles of Black urban culture, fostering institutions, political organizations, and networks that would become indispensable to the Civil Rights Movement.

The Northern experience, while comparatively less oppressive than the Jim Crow South, nonetheless presented new forms of racialized exclusion, including discriminatory housing covenants, employment barriers, and police brutality, demonstrating that systemic racial injustice was national rather than regional in scope. African Americans’ urban consolidation enabled greater visibility, organizational capacity, and the cultivation of alliances with sympathetic White, Jewish, and immigrant communities who recognized the broader moral imperative of racial justice.

The emergence of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1950s and 1960s was predicated upon both the legal groundwork laid by earlier generations and the mobilization of grassroots activism. Landmark cases such as Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 dismantled the constitutional legitimacy of educational segregation, challenging the foundational premises of Jim Crow and establishing a legal rationale for broader desegregation. This legal victory was both a catalyst and a symbol, energizing communities across the nation to engage in direct action campaigns.

African American clergy, students, and ordinary citizens organized sit-ins, freedom rides, boycotts, and marches that dramatized the moral urgency of racial justice, exposing both the brutality of entrenched white supremacy and the ethical imperative for federal intervention. The Montgomery Bus Boycott, the Birmingham campaign, and the March on Washington exemplified a confluence of strategic acumen, moral authority, and communal solidarity that would define the movement’s ethos.

The leadership of figures such as Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Fannie Lou Hamer, Bayard Rustin, and Malcolm X exemplifies the diversity of tactics, ideologies, and visions within the movement. While King emphasized nonviolent civil disobedience and appeals to moral conscience, Malcolm X articulated a critique of systemic oppression that foregrounded Black self-determination and the exigencies of structural power.

Women, often relegated to secondary roles in historical narratives, provided essential organizing, strategizing, and sustaining labor that undergirded every major campaign. These leaders, through their writings, speeches, and organizational prowess, established a lexicon of resistance that informed subsequent movements for justice both within and beyond African American communities.

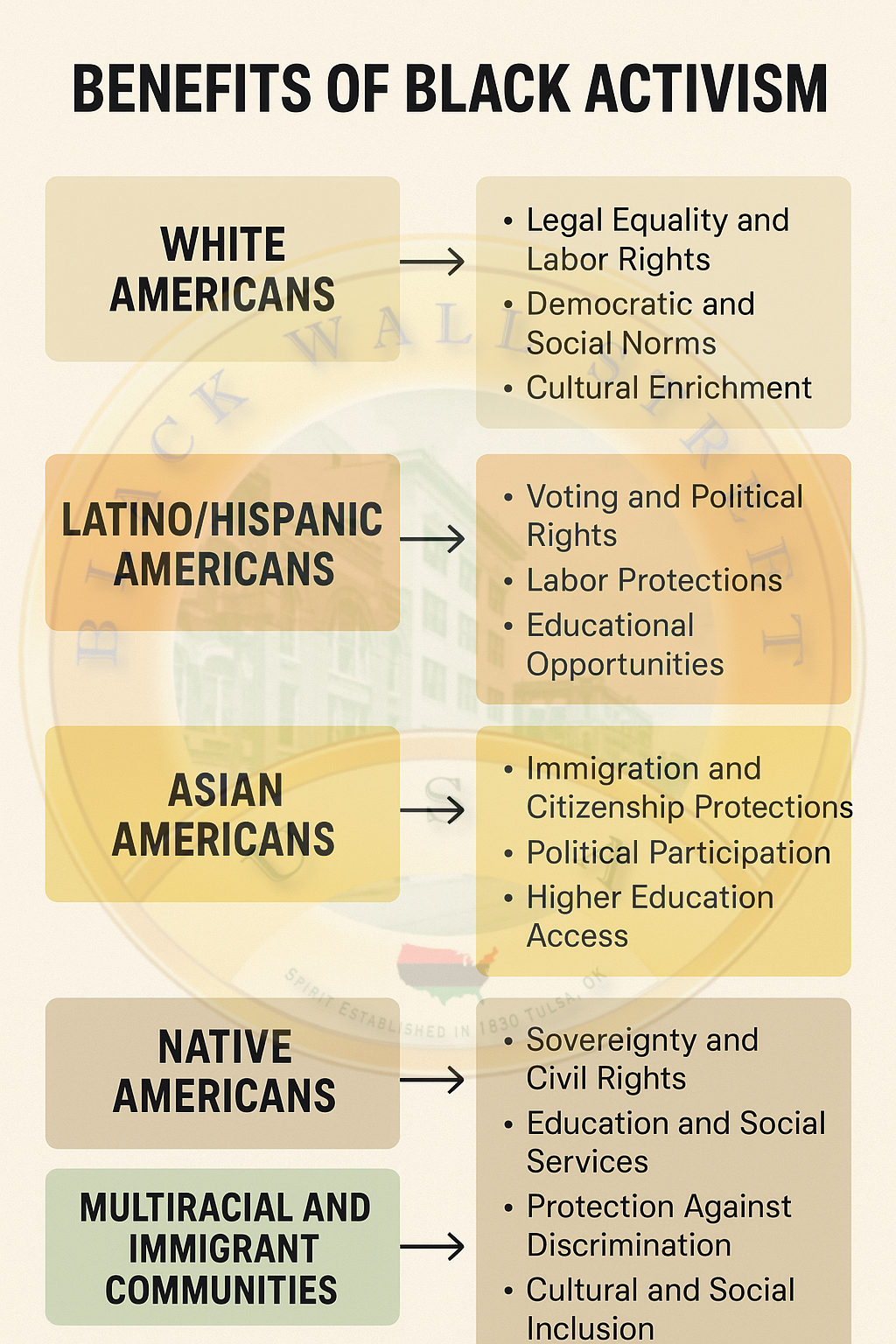

The transformative effects of the Civil Rights Movement extended beyond the African American population, reshaping the legal, political, and cultural terrain of the United States in ways that benefitted a multiplicity of racial and ethnic groups. Legislative enactments such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 established precedents for anti-discrimination enforcement in employment, education, and public accommodations, creating protections that Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Asian Americans, and even marginalized White populations could invoke.

Affirmative action policies, originally designed to redress historical racial inequities for African Americans, became a template for broader social equity initiatives, facilitating access to higher education and professional opportunities for multiple minority communities. The cultural validation of equality and human dignity engendered by the movement catalyzed political mobilization and community organizing across immigrant and indigenous populations, creating a virtuous cycle of activism and legislative reform.

Furthermore, the Civil Rights Movement’s emphasis on coalition-building, moral argumentation, and strategic litigation offered a paradigm for subsequent movements advocating for Native American sovereignty, Asian American immigrant rights, Hispanic labor rights, and Arab American political representation. By articulating a framework in which civil rights were understood as universal rather than parochial, the movement provided intellectual and practical resources for cross-racial advocacy.

The visibility of African American struggle rendered palpable the structural mechanisms of oppression, allowing other communities to identify analogous patterns in their own experiences and to adapt strategies of legal redress, protest, and political negotiation accordingly. The ethos of solidarity and shared humanity embedded in African American activism thus operated as a moral and tactical template across diverse contexts.

Cultural and intellectual transformations, catalyzed by the Civil Rights Movement, also had profound implications for education, media representation, and artistic production. The integration of previously segregated educational institutions, coupled with expanded curricular offerings that foregrounded the histories and contributions of marginalized groups, enabled a generation of scholars, journalists, and creative artists from diverse backgrounds to participate fully in civic life.

Media coverage of the movement—televised images of marches, protests, and police brutality—created a shared national consciousness regarding the moral stakes of racial equality, influencing perceptions and attitudes across racial lines. Literature, music, and visual arts that emerged from or were inspired by the movement provided both aesthetic innovation and ethical instruction, serving as instruments of social critique and intergroup empathy.

In the economic realm, desegregation and anti-discrimination legislation reconfigured access to employment, entrepreneurship, and labor organization. African Americans’ advocacy for equitable labor standards, fair wages, and workplace integration set precedents that extended protections to immigrant laborers, Asian American professionals, and Hispanic agricultural and industrial workers. The movement’s insistence on structural accountability from corporations, public institutions, and municipal governments created mechanisms for monitoring compliance, promoting transparency, and mitigating systemic exclusion, which have enduring effects on economic mobility and workforce diversity.

Politically, the enfranchisement and mobilization strategies pioneered during the Civil Rights Movement created enduring platforms for minority participation in electoral processes. Voting rights advocacy not only empowered African Americans but also informed strategies for enfranchising Native Americans, Hispanic communities, and Asian American citizens. Representation at local, state, and national levels increased, fostering policy environments more responsive to the interests and needs of diverse populations. The movement’s insistence on the inseparability of moral legitimacy and political authority reshaped democratic norms and set standards for accountability and inclusivity that resonate into contemporary governance.

In the contemporary period, the legacies of the African American-led Civil Rights Movement are manifest in ongoing struggles for social justice, equity, and recognition. Movements such as Black Lives Matter, immigrant rights campaigns, Indigenous sovereignty initiatives, and Asian American advocacy draw upon the historical strategies, legal precedents, and moral frameworks forged in the mid-twentieth century. Educational access, anti-discrimination statutes, affirmative action, and multicultural curricula—all fruits of the Civil Rights Movement—continue to benefit communities that had historically been excluded from full participation in American society. Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and other minority groups inhabit a civic landscape indelibly shaped by African American activism, demonstrating the universality of its ethical and structural innovations.

The Civil Rights Movement, therefore, transcends a narrow ethno-racial focus, embodying a paradigm in which justice, equality, and dignity are construed as collective imperatives. By dismantling legal, social, and cultural mechanisms of oppression, African American leaders and communities not only secured rights for themselves but also established a framework through which other marginalized groups could claim inclusion and agency. The movement’s intellectual rigor, strategic sophistication, and moral clarity continue to inform discourses on human rights, equity, and civic responsibility, illustrating that the quest for African American liberation is fundamentally bound to the broader pursuit of justice for all peoples in the United States. Its legacy is not merely historical but living, shaping contemporary debates, policies, and consciousness, and affirming the transformative power of sustained, principled, and visionary activism.

The intricate tapestry of leadership within the Civil Rights Movement reflects a remarkable interplay of strategic acumen, moral authority, and intellectual rigor. Central figures such as Martin Luther King Jr. exemplified the synthesis of religious conviction, philosophical depth, and pragmatic political strategy. King’s articulation of nonviolent resistance, rooted in the theological principles of the African American church and informed by Gandhian praxis, established a template for ethical protest that resonated across diverse communities. His capacity to mobilize multiracial coalitions, appeal to national and international audiences, and translate moral imperatives into tangible political outcomes rendered him emblematic of a movement whose influence transcended any singular locality or constituency. Yet the movement’s successes cannot be reduced to the charisma of its most visible leaders; they were the product of vast networks of organizers, educators, and local activists whose labor, often invisible in mainstream narratives, sustained campaigns across multiple states and municipalities.

Rosa Parks, often symbolically remembered for her refusal to yield her bus seat in Montgomery, exemplified the quotidian courage and strategic foresight that underpinned the movement. Her act was not spontaneous but deeply informed by a lifetime of engagement with civil rights organizations and a nuanced understanding of social leverage. Parks’ refusal catalyzed the Montgomery Bus Boycott, a sustained economic and social campaign that leveraged collective action to dismantle entrenched segregation in public transportation. The boycott illustrated the efficacy of coordinated grassroots mobilization, demonstrating how localized, disciplined, and persistent action could precipitate legal and social transformation. Similarly, figures such as Bayard Rustin provided indispensable strategic infrastructure, organizing logistics for marches, facilitating communication networks, and negotiating complex alliances, thereby ensuring that symbolic gestures were reinforced by operational rigor. Women such as Fannie Lou Hamer infused the movement with ethical gravitas, connecting the struggle for civil rights to broader imperatives of electoral participation and grassroots empowerment, particularly in the rural South where disenfranchisement was most acute.

The movement’s geographical diffusion reveals a sophisticated understanding of the interplay between local contexts and national strategy. In the Deep South, campaigns in Birmingham, Selma, and Montgomery confronted the most virulent forms of Jim Crow repression, utilizing media exposure to elicit national moral outrage and catalyze federal intervention. Nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Greensboro and Nashville exemplified a tactical innovation that combined disciplined physical presence with moral argumentation, compelling institutions to confront the dissonance between their practices and democratic ideals. Freedom Rides traversed the South, intentionally provoking the violent enforcement of segregation to expose systemic injustice and compel federal enforcement of constitutional protections. These campaigns, though regionally situated, were carefully orchestrated to resonate symbolically and politically across the national landscape, creating leverage for comprehensive legislative reform.

The judicial and legislative domains were equally critical to the movement’s strategic architecture. Legal victories such as Brown v. Board of Education established the principle that state-sanctioned segregation violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, undermining the legal rationale for systemic racial exclusion in myriad domains. Subsequent rulings and legislative enactments, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, not only dismantled formal barriers to African American participation but also provided frameworks adaptable to other marginalized communities.

For example, the precedents established in employment discrimination cases facilitated protections for Hispanic farmworkers, Asian American professionals, and Arab American laborers, demonstrating the translatability of African American civil rights victories into broader social equity. Affirmative action programs, originally conceived to remedy historical inequities faced by African Americans, became instruments through which diverse communities gained access to higher education, professional advancement, and civic participation, illustrating the movement’s multiplier effect across racial and ethnic boundaries.

The cross-racial benefits of the Civil Rights Movement were not solely legal or economic; they were deeply cultural and intellectual. The moral and rhetorical framework developed by African American leaders emphasized the universality of justice, human dignity, and democratic accountability, principles that resonated with immigrant communities, indigenous populations, and historically marginalized Whites confronting systemic exclusion. Arab American communities, for instance, engaged with civil rights strategies to challenge religious and ethnic discrimination, particularly in urban centers where patterns of social exclusion mirrored the structures that African Americans had confronted. Indian Americans, particularly those arriving in significant numbers after the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, drew upon the rhetorical and organizational paradigms of African American activism to navigate barriers in higher education, employment, and civic representation.

Similarly, Hispanic and Latino communities leveraged lessons from African American voter mobilization and labor organizing to advance farmworker rights, bilingual education, and political enfranchisement, while Asian American activists employed legal precedents and coalition-building strategies to contest discriminatory housing covenants and exclusionary immigration policies. Native American communities, engaged in struggles for sovereignty, tribal recognition, and self-determination, similarly benefitted from the jurisprudential and tactical lessons of African American civil rights campaigns, adapting them to the specific contours of treaty law, federal oversight, and indigenous governance structures.

The economic implications of the movement further illustrate its pan-ethnic significance. Workplace desegregation, access to professional networks, and enforcement of anti-discrimination statutes created conditions under which multiple marginalized groups could contest exclusion and pursue upward mobility. The Civil Rights Movement established mechanisms for corporate accountability and state regulation that provided structural support to diverse populations seeking entry into sectors historically dominated by privileged groups. Labor unions, initially constrained by racial hierarchies, became sites of interracial and interethnic collaboration, fostering solidarity and enhancing collective bargaining power across multiple minority constituencies. African American advocacy for equitable labor practices thus became a structural conduit through which Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American workers could access protections and institutional recognition, reinforcing the movement’s expansive reach.

Culturally, the movement generated a profound reconfiguration of public consciousness regarding the ethics of inclusion, representation, and civic participation. African American literature, music, and visual arts served as both testimonial and pedagogical tools, documenting oppression, celebrating resilience, and inspiring solidaristic action. Media coverage of protests, police brutality, and grassroots organization created national narratives that transcended local contexts, fostering empathy and moral alignment across racial and ethnic lines. Educational reforms, including curriculum diversification and the integration of African American history into mainstream pedagogy, offered frameworks that validated the experiences of multiple marginalized communities while cultivating a more expansive conception of citizenship and civic responsibility. The aesthetic, moral, and intellectual output of the Civil Rights Movement thus operated as a catalyst for cultural and institutional transformation that reverberated across all strata of American society.

Politically, the enfranchisement and mobilization strategies pioneered by African Americans redefined participatory democracy in the United States. By asserting the inviolability of the right to vote and the necessity of representative governance, the movement provided a procedural and moral template for other minority communities seeking political agency. Hispanic and Latino populations utilized similar strategies in the Southwest and California to challenge gerrymandering, voter suppression, and unequal representation.

Asian Americans, particularly in the wake of civil rights jurisprudence and advocacy models, engaged in political mobilization to combat restrictive immigration policies and expand community representation. Native American activists leveraged the movement’s organizational and rhetorical strategies to press for the recognition of treaty rights, land reclamation, and the expansion of tribal governance authority. Even White Americans who were socioeconomically marginalized found in the movement’s framework both ethical validation and procedural strategies for contesting structural inequities. The Civil Rights Movement, in sum, reshaped the political architecture of the nation, embedding principles of accountability, equity, and moral legitimacy that continue to influence policy and civic engagement.

The movement’s enduring significance is also evident in contemporary activism and policy discourse. Initiatives addressing systemic racism, immigrant rights, Indigenous sovereignty, gender equity, and religious freedom draw explicitly upon the legal precedents, strategic frameworks, and moral lexicon developed by African American leaders in the mid-twentieth century. Movements such as Black Lives Matter, DREAMer advocacy campaigns, and Native American land-rights litigation demonstrate the living legacy of civil rights strategies, illustrating the continued relevance of coalition-building, moral argumentation, and disciplined activism. Moreover, contemporary debates on affirmative action, reparations, policing reform, and educational equity remain inextricably linked to the intellectual, tactical, and ethical foundations laid by the African American-led Civil Rights Movement, underscoring the enduring pan-ethnic and national impact of this historic struggle.

In synthesizing these threads, it becomes evident that the African American Civil Rights Movement constitutes a paradigmatic model of transformative social struggle. Its achievements were not circumscribed by the narrow parameters of a single racial constituency but radiated outward, reshaping legal, political, cultural, and economic domains in ways that benefitted a multitude of communities. By confronting entrenched hierarchies of power, articulating a universalist moral vision, and operationalizing sophisticated strategies of collective action, African Americans forged pathways through which Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Native Americans, Asian Americans, and marginalized White Americans could assert their rights, claim institutional recognition, and participate fully in the civic, economic, and cultural life of the nation. The movement thus exemplifies the principle that the liberation of one group is inextricably linked to the liberation of all, illustrating the interdependence of justice, democracy, and human dignity in a pluralistic society.

The Southern theater of the Civil Rights Movement represents both the crucible of resistance and the epicenter of violent opposition, producing a terrain in which strategic acumen, moral authority, and communal solidarity were tested to their utmost limits. States such as Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Georgia, with their entrenched Jim Crow apparatuses, offered both stark evidence of institutionalized subjugation and the opportunity for highly visible campaigns capable of national moral resonance. The rural and urban interplay within these states created distinct but interdependent arenas for activism. In rural counties, disenfranchisement was enforced through literacy tests, poll taxes, and the threat of extrajudicial violence, rendering political participation a matter of existential courage. Activists such as Fannie Lou Hamer, whose experiences of both oppression and mobilization epitomized the dual burdens of gender and race, spearheaded voter registration initiatives that confronted local authorities while linking grassroots agency to broader federal enforcement mechanisms. Hamer’s work, while focused on African American enfranchisement, generated procedural models and ethical frameworks subsequently utilized by Hispanic communities in Texas and New Mexico, who confronted analogous patterns of electoral suppression and systemic exclusion.

Urban Southern centers, including Birmingham and Montgomery, became laboratories for highly choreographed demonstrations designed to elicit media attention and compel federal intervention. The Birmingham campaign, orchestrated by Martin Luther King Jr., Fred Shuttlesworth, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, combined boycotts, marches, and children’s crusades to dramatize the moral urgency of dismantling segregation. The resulting images of police dogs, fire hoses, and mass arrests broadcast into living rooms across the nation created an unprecedented moral spectacle that galvanized public opinion and precipitated legislative action. The strategic sophistication of these campaigns rested not only on ethical appeals but also on the meticulous coordination of logistics, communications, and legal support—functions often orchestrated by unsung organizers such as Ella Baker, whose emphasis on decentralized leadership and participatory democracy ensured broad-based engagement and sustained organizational capacity.

In Mississippi, the Freedom Summer of 1964 exemplified the convergence of legal strategy, grassroots organizing, and intergenerational solidarity. Volunteer networks, drawn from northern universities and local communities, engaged in voter education, registration drives, and the establishment of Freedom Schools to provide pedagogical alternatives to segregated curricula. The violent backlash, including the murders of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, underscored the lethal stakes of activism, yet simultaneously provoked national outrage and legislative momentum.

These events illuminated both the perilous conditions under which civil rights work was conducted and the strategic efficacy of exposing systemic injustice to public scrutiny. Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American communities, observing and participating in these campaigns, adapted similar strategies in their own struggles for educational equity and political representation, drawing upon the legal precedents and organizational methodologies refined by African American activists.

Legal victories across the South and beyond reinforced and institutionalized these gains. The integration of public education, first symbolically through Brown v. Board of Education and subsequently through judicial oversight of local school boards, created mechanisms that facilitated broader access for multiple minority communities. Indian Americans and Asian Americans benefited from desegregation policies in urban and suburban schools, which expanded opportunities for higher education and professional advancement. Hispanic students, particularly in the Southwest, leveraged these precedents to challenge de facto segregation and advocate for bilingual education programs that acknowledged linguistic and cultural diversity. Native American communities drew upon these judicial frameworks to assert educational sovereignty and to establish tribally controlled schools that combined federal standards with indigenous cultural preservation, illustrating the multifaceted reach of African American-led legal interventions.

The Northern theater presented distinct dynamics, in which systemic inequality was less overtly codified yet no less pernicious. Urban segregation, discriminatory housing covenants, and employment barriers created concentrations of marginalized populations within industrial and post-industrial cities. Activists in Chicago, Detroit, and New York, including the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), adapted Southern strategies to Northern realities, organizing rent strikes, employment advocacy campaigns, and educational initiatives.

These campaigns demonstrated that systemic inequities could not be addressed solely through legal adjudication but required sustained, coordinated civic action. Arab Americans in urban centers such as Dearborn, Michigan, observed and participated in these efforts, mobilizing around housing discrimination and labor rights, while Indian American professionals leveraged lessons in political organizing to secure access to municipal boards and civic institutions. Hispanic and Latino populations similarly benefited from Northern campaigns, gaining models for coalition-building and advocacy that informed labor organizing, bilingual education initiatives, and electoral engagement.

The Western United States, encompassing California, Washington, and the Pacific Northwest, presented a terrain of both opportunity and resistance. Mexican American communities in Oakland, Los Angeles and San Antonio drew upon African American civil rights strategies to contest school segregation, police discrimination, and employment inequities. Asian American communities, including Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino populations, utilized the rhetorical and legal templates of the movement to challenge exclusionary immigration policies and discriminatory labor practices. Native American populations on reservations and in urban areas engaged with civil rights precedents to assert sovereignty, advocate for treaty enforcement, and pursue economic development initiatives. In each regional context, the interplay between local conditions and national frameworks highlighted the adaptability of African American strategic innovations, illustrating the movement’s capacity to generate cross-racial benefits in diverse social, political, and geographic milieus.

Biographical studies of lesser-known activists illuminate the movement’s expansive social infrastructure. Individuals such as Septima Poinsette Clark, whose establishment of citizenship schools empowered thousands of African Americans to register to vote, also provided pedagogical templates adaptable to immigrant communities navigating language barriers and political marginalization. Diane Nash, through her leadership in student organizing and the Freedom Rides, exemplified the capacity of youth activism to catalyze structural change, a model subsequently employed by Asian American and Hispanic student organizations in the pursuit of educational equity. The participation of multiracial coalitions, including Jewish Americans, sympathetic Whites, and immigrant groups, reinforced the principle that the ethical and strategic dimensions of the movement were inherently universal, demonstrating that African American-led activism could serve as a generative force for broad social reform.

Cultural transformations paralleled legal and political achievements. Music, literature, and visual arts served as both documentation and mobilization, shaping national consciousness and providing moral exemplars for action. The literary contributions of James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, and Richard Wright articulated the psychological and social ramifications of systemic oppression while offering paradigms of resistance. Musical innovations, from spirituals to gospel to the emergent rhythm and blues that intersected with protest music, conveyed the emotional tenor of struggle and inspired solidaristic engagement across racial lines. Media exposure of civil rights campaigns generated a shared moral consciousness, prompting Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, and Native communities to recognize structural parallels in their own experiences and to adapt strategies of advocacy, legal challenge, and organized protest.

Economically, the Civil Rights Movement established mechanisms for equitable participation in labor and commerce that transcended the African American community. Affirmative action, employment protections, and corporate accountability measures facilitated access for multiple marginalized groups, creating pathways for social mobility and the dismantling of institutional barriers. Arab American small business owners, Indian American professionals, and Hispanic agricultural and industrial workers benefited from these structural reforms, which reduced overt discrimination and opened previously closed networks of opportunity. Similarly, unions that had historically excluded African Americans were compelled to integrate, producing a model of labor solidarity that could accommodate diverse ethnic constituencies and advocate for broader social justice.

The intellectual and ethical paradigms of the Civil Rights Movement also influenced contemporary policy discourse. Debates surrounding affirmative action, reparations, police reform, educational equity, and immigrant rights continue to draw upon the moral authority, strategic frameworks, and legal precedents established by African American activism. By situating African American liberation within a universalist framework of justice and human dignity, the movement provided a foundational lexicon for cross-racial advocacy, enabling Arab Americans to contest profiling and discrimination, Indian Americans to address professional and educational inequities, Hispanic and Latino populations to challenge labor and political marginalization, Asian Americans to assert civil rights protections, and Native Americans to advance sovereignty and self-determination.

In synthesizing regional, biographical, legal, cultural, and economic dimensions, the Civil Rights Movement emerges not merely as a historical struggle for African American emancipation but as a paradigmatic model of systemic transformation whose benefits radiated across racial, ethnic, and geographic boundaries. Its enduring legacy is evident in contemporary social, political, and economic structures, in the ethical frameworks guiding civic engagement, and in the continued mobilization of communities seeking justice, equity, and recognition. The movement exemplifies the principle that the advancement of one oppressed group enhances the structural and moral integrity of society as a whole, demonstrating the inextricable linkage between African American liberation and the broader pursuit of democratic, egalitarian, and pluralistic ideals.

The jurisprudential innovations catalyzed by the African American-led Civil Rights Movement constitute one of its most enduring legacies, producing a body of legal precedent that reshaped the American understanding of equality, due process, and civil liberties. Central to this transformation were landmark decisions that dismantled the scaffolding of legalized racial subordination, beginning with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), which repudiated the doctrine of “separate but equal” and mandated the desegregation of public schools.

This judicial pronouncement, while directly addressing the educational marginalization of African American children, also established a principle of constitutional fidelity to equality that became instrumental for other communities confronting systemic exclusion. Hispanic students in California and Texas leveraged the rationale articulated in Brown to challenge segregated classrooms and inadequate funding, leading to the emergence of bilingual education programs that addressed linguistic and cultural marginalization. Asian American students similarly invoked these precedents to contest discriminatory school admissions and tracking practices, while Native American communities utilized the principles enunciated to advocate for educational sovereignty and tribal school systems that combined cultural preservation with federally mandated standards.

Subsequent judicial decisions further entrenched these protections and expanded their applicability. Cases such as Loving v. Virginia (1967), which invalidated prohibitions on interracial marriage, and Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971), which addressed employment discrimination, demonstrated the flexibility and universality of civil rights jurisprudence. Arab Americans, often subject to religious and ethnic discrimination in housing and employment, drew upon these decisions to establish legal claims under anti-discrimination statutes.

Indian Americans, particularly professionals in corporate and academic spheres, utilized the emerging body of affirmative action jurisprudence to challenge exclusionary practices and secure access to opportunities historically reserved for majority groups. Hispanic and Latino communities relied on voting rights litigation informed by the Civil Rights Act and subsequent court interpretations to challenge gerrymandered districts and restrictive electoral practices, thereby increasing political representation and participation. Native American tribes employed these legal frameworks to assert treaty rights, contest federal neglect, and negotiate for economic and educational resources, highlighting the movement’s systemic and cross-ethnic impact.

Education, as both a locus of inequality and a mechanism for social mobility, was profoundly transformed by the Civil Rights Movement. Beyond desegregation, African American advocacy catalyzed the development of citizenship schools, curriculum reforms, and higher education access programs that benefitted multiple marginalized populations. Septima Poinsette Clark’s citizenship schools, originally designed to empower African Americans with literacy and political knowledge necessary for voter registration, offered a pedagogical model adapted by immigrant communities, including Hispanic, Arab, and Asian American populations, who faced barriers to civic engagement due to linguistic, cultural, or bureaucratic obstacles.

Similarly, initiatives to expand access to historically white universities, often through affirmative action programs, enabled a generation of Indian Americans, Asian Americans, and Hispanic students to enter professional and academic fields from which they had been previously excluded. These reforms not only enhanced individual opportunity but also reconfigured institutional cultures, fostering greater diversity in faculty, administration, and curricular content, which in turn enriched the intellectual environment for all students, regardless of background.

The economic implications of the Civil Rights Movement were equally expansive. African American activism precipitated the enforcement of employment protections, equitable labor standards, and access to entrepreneurial opportunities. Court-mandated desegregation in workplaces and affirmative action initiatives compelled corporations to re-evaluate hiring practices, promoting diversity in sectors such as law, medicine, engineering, and finance. Arab American business owners, Indian American professionals, and Hispanic and Asian American entrepreneurs benefited from these systemic interventions, which reduced discriminatory barriers and provided access to capital, networks, and institutional legitimacy. Labor unions, long constrained by racial hierarchies, integrated African American members and developed protocols for equitable representation, setting precedents that allowed other marginalized groups to negotiate fair wages, benefits, and working conditions. The Civil Rights Movement’s insistence on structural accountability thus generated a multiplier effect, extending the benefits of economic justice beyond the immediate African American constituency.

Cultural production, encompassing literature, visual arts, music, and media representation, emerged as both a reflection of African American struggle and a pedagogical instrument for fostering cross-racial solidarity. Writers such as James Baldwin, Maya Angelou, and Toni Morrison articulated the existential and systemic dimensions of oppression, providing moral and intellectual frameworks that resonated with Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American audiences confronting analogous inequities. Visual artists, photographers, and filmmakers documented both the brutality of repression and the dignity of resistance, shaping public perception and inspiring solidaristic activism. Music, from gospel and blues to rhythm and blues, functioned as both aesthetic expression and social commentary, cultivating empathy and mobilizing audiences across racial and ethnic lines. The widespread media coverage of protests, court rulings, and grassroots organizing disseminated these cultural narratives nationally and internationally, embedding principles of equality, justice, and civic responsibility into the collective consciousness.

The intersection of legal, educational, economic, and cultural reforms produced profound political transformations. African American voter registration campaigns, participation in local governance, and federal legislative advocacy established models for political mobilization subsequently adopted by other minority communities. Hispanic and Latino populations employed similar strategies to challenge systemic disenfranchisement, culminating in increased representation in city councils, state legislatures, and Congress. Asian American activists drew upon the organizational techniques and rhetorical strategies of the Civil Rights Movement to advocate for equitable educational access, immigration reform, and civil rights protections. Native American communities applied these methodologies to assert sovereignty, secure funding for social programs, and negotiate with federal agencies, illustrating the adaptive capacity and universality of African American strategic innovations. The political efficacy of these interventions not only enfranchised specific constituencies but also reinforced democratic norms and participatory frameworks that strengthened the overall civic architecture of the nation.

Contemporary policy discourse continues to reflect the enduring influence of the Civil Rights Movement. Debates surrounding affirmative action, police reform, immigration policy, educational equity, and labor rights are infused with the jurisprudential, moral, and organizational legacies established by African American activism. Arab Americans utilize civil rights frameworks to challenge profiling and discrimination, Indian Americans to secure equitable professional opportunities, Hispanic and Latino populations to advocate for bilingual education and labor protections, Asian Americans to contest exclusionary practices, and Native Americans to assert land rights and cultural preservation initiatives. Even socioeconomically marginalized White Americans derive procedural and ethical benefits from these systemic reforms, demonstrating the universality and expansive reach of the movement’s interventions. The African American-led Civil Rights Movement thus operates as a continuous, living precedent, informing contemporary strategies for social justice, equity, and institutional accountability.

In synthesizing the legal, educational, economic, cultural, and political dimensions, it becomes evident that the Civil Rights Movement functioned as a generative engine of societal transformation. Its innovations created mechanisms through which multiple racial and ethnic communities could assert rights, achieve institutional recognition, and participate meaningfully in the civic, economic, and cultural life of the nation.

By articulating a universalist moral and strategic framework, African American activists forged pathways that facilitated cross-racial solidarity and systemic reform, demonstrating that the struggle for African American liberation is fundamentally entwined with the broader pursuit of justice for all marginalized communities. The movement’s enduring impact is manifest not only in tangible legislative and institutional outcomes but also in the ethical, intellectual, and cultural paradigms that continue to guide contemporary activism, public policy, and civic engagement.

The rich mosaic of leadership within the Civil Rights Movement extends far beyond the most widely celebrated figures, encompassing a constellation of organizers, educators, clergy, and activists whose labor, intellectual contributions, and moral courage were indispensable to the movement’s achievements. Figures such as Septima Poinsette Clark, Ella Baker, Diane Nash, John Lewis, and Fannie Lou Hamer provided the strategic, educational, and logistical frameworks that enabled campaigns to flourish under circumstances of extraordinary adversity. These leaders cultivated networks that bridged local, regional, and national spheres, demonstrating the efficacy of decentralized yet coordinated activism. Their efforts were instrumental not merely in securing rights for African Americans but also in creating templates of civic engagement, legal advocacy, and community organization that other marginalized groups could emulate. Arab Americans navigating anti-Muslim prejudice, Indian Americans confronting barriers in education and professional spheres, Hispanic and Latino populations seeking labor justice, Asian Americans contesting exclusionary immigration and employment practices, and Native American communities asserting sovereignty all drew upon these precedents, illustrating the universality of African American strategic innovations.

The transmission of these lessons was not incidental but deliberate, reflecting the ethical and intellectual sophistication of African American activism. Grassroots schools, voter education programs, and legal training initiatives provided the knowledge and practical skills that facilitated broader engagement in civic life. The Citizenship Schools pioneered by Clark, for instance, offered instruction in literacy and political participation that transcended racial boundaries, providing immigrant and indigenous populations with critical tools for navigating civic structures. Similarly, the moral and rhetorical frameworks developed by Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, and other leaders emphasized principles of justice, equity, and human dignity that resonated universally. These frameworks enabled other communities to recognize patterns of structural oppression within their own contexts, adapt tactics of advocacy, and pursue legal and social remedies. In this sense, the movement was both particular and universal, addressing the specific historical injustices faced by African Americans while generating strategies and principles applicable across diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural contexts.

Yet, despite the breadth of these contributions and their benefits to all Americans, there persists a profound ethical and historical deficit in recognition and gratitude. African Americans have borne the weight of systemic oppression from the inception of the republic, enduring slavery, segregation, economic disenfranchisement, and violent suppression of civic agency, yet the acknowledgment of their labor, intellect, and moral leadership remains insufficient. The ethical imperative for other racial and ethnic groups is to cultivate a consciousness informed by both historical awareness and present accountability, recognizing that the legal, social, economic, and cultural frameworks they now inhabit are in significant measure products of African American struggle. Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and even socially marginalized White Americans derive direct and indirect benefits from the dismantling of Jim Crow, the establishment of voting rights protections, workplace desegregation, affirmative action policies, and expanded access to higher education. To neglect acknowledgment or to appropriate these benefits without gratitude constitutes both a moral failure and an erosion of civic integrity.

The responsibility of recognition extends beyond symbolic gestures; it requires active engagement in dismantling residual inequities, confronting persistent anti-Black bias, and advancing policies that honor the centrality of African American contributions. Contemporary debates over policing, criminal justice reform, reparations, educational equity, and economic inclusion underscore that African Americans continue to experience structural disadvantage, even as other communities benefit from frameworks historically established through Black struggle.

Arab Americans contest profiling and discrimination in law enforcement, Indian Americans and Asian Americans navigate professional hierarchies still influenced by racialized exclusion, Hispanic and Latino communities confront educational and labor inequities, and Native Americans struggle for the enforcement of treaty rights and sovereignty. In each case, the successes and protections enjoyed by these communities are deeply intertwined with African American advocacy, legal victories, and moral leadership. Recognition and gratitude are thus not mere abstractions but ethical obligations that demand both acknowledgment and active commitment to justice for African Americans in the present.

The ethical dimension of this historical debt is reinforced by the demographic and structural realities of American society. African Americans constitute a foundational constituency in urban centers, political coalitions, labor movements, and cultural production, shaping the nation’s civic, social, and economic landscape. The ethical imperative for other communities is to situate their advancement within a framework that acknowledges African American ancestry and ongoing contributions, cultivating a relational consciousness that resists appropriation, erasure, or indifference. This entails recognition of the historical foundations of American wealth, social institutions, legal protections, and democratic norms, all of which were profoundly shaped by African American struggle and sacrifice. Moreover, it requires active engagement in policies, programs, and social practices that honor Black agency, foster equity, and dismantle persistent racial hierarchies. Gratitude, in this sense, is inseparable from justice, functioning both as moral acknowledgment and as a practical commitment to collective social responsibility.

The movement’s regional dynamics, when examined through the lens of cross-racial impact, further illuminate this ethical imperative. In the rural South, voter registration campaigns, civil disobedience, and grassroots organizing produced procedural and strategic frameworks now utilized by Hispanic, Arab, and Native communities to assert political agency. In urban Northern centers, campaigns for educational access, housing equity, and employment opportunity provided models subsequently adapted by Indian, Asian, and immigrant populations confronting structural barriers. In the Western states, advocacy for school desegregation, labor rights, and civic participation reflected lessons derived from African American strategies, illustrating the extensive diffusion of methodological and ethical innovation. Across these geographies, the tangible benefits for other racial and ethnic groups are inseparable from the historical labor, intellectual capital, and moral courage of African Americans. The ethical mandate, therefore, is for these communities to recognize, respect, and honor that foundational contribution, integrating gratitude into both civic discourse and social praxis.

Contemporary cultural and intellectual production continues to reflect the moral and strategic insights of the Civil Rights Movement, offering further avenues for acknowledgment and respect. Literature, music, film, and scholarship foregrounding African American struggle and achievement constitute resources from which other communities draw knowledge, inspiration, and ethical guidance. To engage with these resources without acknowledgment or to abstract their utility from the context of African American struggle constitutes a form of erasure that undermines both historical truth and contemporary ethical responsibility.

Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, Native, and White populations benefit from the pedagogical, jurisprudential, and cultural infrastructure established through African American leadership; recognition of this fact is both a moral imperative and a practical foundation for cross-racial solidarity. Gratitude, in this sense, functions as a form of civic literacy, ethical awareness, and social cohesion, reinforcing the principle that the liberation and advancement of one community are inseparably connected to the recognition and support of the foundational labor of another.

In synthesizing leadership, legal innovation, regional campaigns, cultural production, and ethical responsibility, it becomes clear that the African American-led Civil Rights Movement constitutes a paradigmatic model not only of social transformation but also of moral and civic leadership. Its strategies, victories, and ongoing relevance have produced measurable benefits for Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and marginalized Whites, while simultaneously highlighting the ethical obligation to honor and respect African American ancestry and contemporary citizenship.

Recognition, respect, and gratitude are not optional adjuncts to historical knowledge; they are essential components of civic ethics, social justice, and intergroup solidarity. The movement’s legacy, therefore, is both material and moral, encompassing legal protections, educational opportunities, economic pathways, cultural enrichment, and an ethical framework that continues to guide the nation toward a more just, inclusive, and equitable society.

The historiography of the Civil Rights Movement is enriched by a constellation of leaders whose strategic acumen, moral authority, and intellectual rigor provided both the ethical and operational foundations of transformative social change. Among these figures, John Lewis stands as a paragon of courage and procedural sophistication. His leadership within the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and his pivotal role in the Selma to Montgomery marches exemplify the integration of moral conviction, disciplined organization, and legal strategy.

Lewis’s insistence on nonviolent protest, coupled with his engagement in legislative advocacy, created a model subsequently adapted by Hispanic and Latino youth organizations in voter registration campaigns throughout Texas and California. Similarly, Ella Baker’s emphasis on decentralized leadership and grassroots empowerment provided the ethical and structural template through which Arab American community organizers mobilized against discriminatory housing policies in Detroit and Dearborn. Baker’s insistence that power and knowledge reside within the community, rather than solely in charismatic leaders, facilitated an enduring methodology for participatory democracy that transcended racial and ethnic boundaries.

Fannie Lou Hamer, with her unparalleled combination of moral courage and strategic foresight, exemplifies the intersection of individual resilience and collective agency. Her work in Mississippi’s Freedom Summer illuminated the structural mechanisms of disenfranchisement while offering tangible pathways to civic engagement through voter registration and political education. Hamer’s methods informed similar initiatives in Hispanic and Native American communities confronting systemic barriers to electoral participation, demonstrating the transferability of African American strategies to diverse contexts. Diane Nash, a leader in both the Nashville sit-ins and the Freedom Rides, combined legal acumen, tactical creativity, and ethical clarity, providing a roadmap for Asian American and Indian American student organizations advocating for educational equity and civil rights protections. Septima Poinsette Clark’s citizenship schools, as previously noted, extended these lessons by institutionalizing literacy, civic knowledge, and political participation as vehicles of empowerment, models that were subsequently adapted by multiple immigrant and indigenous communities seeking both legal and cultural recognition.

The regional diffusion of Civil Rights strategies illuminates the movement’s adaptability and its pan-ethnic significance. In the Deep South, campaigns in Birmingham, Montgomery, Selma, and Jackson directly confronted the most virulent forms of legal and extralegal racial oppression. Arab American communities in urban centers such as Birmingham drew upon these precedents to challenge religious profiling and employment discrimination, employing grassroots organizing and legal action modeled after African American campaigns. Hispanic and Latino populations in the Mississippi Delta and Texas engaged in voter mobilization and labor organizing using strategies derived from African American activism, adapting them to address the unique intersections of ethnicity, language, and class.

Native American communities utilized legal and organizational frameworks from Southern campaigns to assert sovereignty, secure federal recognition, and protect educational and economic resources. In the Northern states, African American-led urban campaigns provided templates for challenging de facto segregation in housing, employment, and education, frameworks that were subsequently applied by Indian and Asian American communities confronting structural inequities in cities such as Boston, Chicago, New York, Los Angeles and Oakland.

The jurisprudential impact of African American activism extends across ethnic and racial boundaries. Landmark cases, including Brown v. Board of Education, Loving v. Virginia, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., and Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, established principles of equality, due process, and anti-discrimination that were leveraged by other communities to contest exclusionary practices. Arab Americans, particularly in the aftermath of the 1965 and 1980s immigration influxes, drew upon these precedents to challenge religious and ethnic discrimination in employment and housing. Indian Americans utilized affirmative action jurisprudence to secure access to higher education and professional advancement, while Asian Americans engaged legal frameworks to contest discriminatory immigration policies and employment practices.

Hispanic and Latino communities applied voting rights jurisprudence to challenge gerrymandered districts, literacy tests, and other mechanisms of political marginalization. Native American communities incorporated civil rights litigation strategies into broader campaigns for tribal sovereignty, land rights, and cultural preservation. These cross-racial applications of African American legal victories underscore both the universality and the ethical significance of Black struggle, highlighting the imperative for acknowledgment and respect from all beneficiaries.

Cultural and educational transformations further illustrate the movement’s pan-ethnic impact. African American literature, music, and visual arts produced during and after the Civil Rights era generated moral, aesthetic, and intellectual frameworks subsequently drawn upon by other communities. The narrative works of James Baldwin, Richard Wright, and Maya Angelou, alongside the protest and gospel music of the era, shaped public consciousness, providing both testimony of oppression and models for ethical engagement.

Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, and Native communities have incorporated these cultural forms into their own struggles, using them as pedagogical tools, sources of inspiration, and ethical frameworks for organizing. Education reform, particularly in higher education access and curriculum diversification, created spaces in which multiple marginalized groups could attain opportunities previously denied to them. African American advocacy for equitable schooling, integration, and citizenship education thus became a vehicle through which other racial and ethnic communities could assert their rights and gain institutional recognition.

Economically, the Civil Rights Movement’s interventions created pathways for broader inclusion. The dismantling of employment discrimination, establishment of workplace protections, and expansion of affirmative action policies facilitated access to professional networks, capital, and opportunities for Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, and Native populations. Labor union integration, workplace equity initiatives, and legal protections reinforced structural inclusion, generating pathways for social mobility across racial lines.

These economic gains are inseparable from the labor, courage, and strategic innovation of African Americans, underscoring the ethical imperative for other communities to recognize and honor these contributions. Respect and gratitude, in this context, are not mere abstractions but essential components of intergroup solidarity and civic responsibility.

Contemporary social movements continue to draw upon African American strategies, demonstrating both the longevity and universality of the Civil Rights Movement’s impact. Black Lives Matter, immigrant rights campaigns, Indigenous sovereignty advocacy, and Asian American anti-discrimination initiatives all employ frameworks of moral persuasion, grassroots mobilization, legal advocacy, and coalition-building pioneered by African American activists.

Arab Americans confronting profiling, Indian Americans navigating systemic professional barriers, Hispanic and Latino populations contesting voter suppression, and Native Americans asserting treaty rights all utilize methodologies and moral paradigms that are deeply indebted to African American leadership. The ethical imperative, therefore, is for these communities to recognize and honor their debt, integrating respect and gratitude into both civic discourse and praxis, acknowledging that African American struggle produced the legal, social, economic, and cultural frameworks upon which their own advancements are built.

In synthesizing these strands of leadership, regional strategy, legal precedent, cultural production, educational reform, and economic inclusion, it becomes incontrovertibly clear that the African American-led Civil Rights Movement was both a particular struggle against racial oppression and a generative framework benefiting all marginalized communities. Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and marginalized Whites have all derived concrete and intangible benefits from African American activism.

This historical and ongoing indebtedness establishes an ethical imperative: all beneficiaries must demonstrate respect and gratitude toward African American ancestry and contemporary citizens. Recognition, honor, and active support for equity initiatives constitute both moral acknowledgment and practical fulfillment of civic responsibility. The struggle for justice, initiated and led by African Americans, is thus inseparable from the broader pursuit of an inclusive, equitable, and morally coherent society, one in which gratitude and respect are foundational, as essential as the legal, economic, and cultural gains that the movement has engendered.

The Civil Rights Movement’s strategies and principles were neither static nor confined solely to the African American experience; they became adaptable tools through which diverse communities could contest structural inequities, asserting rights and advancing civic participation. The experiences of Hispanic and Latino communities vividly illustrate this cross-racial application. In Texas, California, and the Southwest, Mexican American farmworkers and urban residents confronted systemic disenfranchisement, educational marginalization, and exploitative labor conditions.

Leaders such as César Chávez and Dolores Huerta explicitly drew upon the organizational tactics pioneered by African American activists—boycotts, strikes, nonviolent protest, and coalition-building—translating them into campaigns for labor rights, bilingual education, and political representation. The moral and rhetorical frameworks of African American leaders, emphasizing dignity, equity, and human rights, informed these strategies, demonstrating the ethical universality and operational adaptability of civil rights activism. The tangible gains in labor conditions, political enfranchisement, and educational access underscore the direct material and structural benefits derived from African American struggle, reinforcing the ethical obligation of acknowledgment and respect.

Similarly, Asian American communities have employed Civil Rights Movement frameworks to navigate and contest structural barriers in education, employment, and immigration policy. The experiences of Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, and South Asian populations illustrate the intersection of racialized exclusion with immigration status and cultural marginalization. The landmark case Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), concerning affirmative action in higher education, drew upon precedents established by African American legal advocacy, providing a basis for Asian American students to challenge discriminatory admissions policies. Grassroots organizing, coalition-building, and strategic litigation, informed by African American methodologies, facilitated access to educational and professional opportunities that had previously been restricted. Beyond legal and educational gains, these strategies reinforced civic literacy and political agency, allowing Asian American communities to assert representation and influence policy at local, state, and national levels, further illustrating the generative impact of African American activism across racial lines.

Arab American communities, particularly in urban centers, have similarly benefitted from the strategic templates and legal precedents established by African American activism. From confronting discriminatory housing policies in Detroit to challenging post-9/11 profiling and civil liberties violations, Arab American organizers have adapted nonviolent protest, grassroots mobilization, and coalition-building techniques to resist systemic inequities. Legal frameworks originating in the Civil Rights Movement, including anti-discrimination statutes, voting rights protections, and employment equality provisions, have provided the structural foundation for these interventions. The transference of strategy, alongside the ethical and rhetorical paradigms cultivated by African American leaders, underscores the moral and practical necessity for Arab Americans to recognize the foundational role of African American struggle in enabling contemporary civic and legal engagement.

Native American communities similarly drew upon African American strategic and legal precedents to assert sovereignty, secure treaty rights, and pursue educational and economic development initiatives. The occupation of Alcatraz Island, the Trail of Broken Treaties, and campaigns for federal recognition of tribal status all reflected the influence of African American nonviolent protest, legal advocacy, and organizational frameworks. These movements combined grassroots mobilization with legal and moral argumentation, demonstrating the transferability of African American civil rights strategies to struggles for indigenous self-determination. Moreover, Native American educational initiatives, modeled on African American citizenship and literacy programs, reinforced cultural preservation while promoting civic participation, further illustrating the multi-dimensional, pan-ethnic benefits of Civil Rights Movement innovations.

The ethical dimension of these cross-racial benefits cannot be overstated. While Arab, Indian, Hispanic, Asian, and Native American communities have derived substantial legal, economic, educational, and political advantages from African American activism, recognition and gratitude often remain limited. This ethical deficit undermines both historical accuracy and contemporary social cohesion. African American ancestors and present-day citizens provided not only the labor, strategy, and leadership that enabled structural change, but also the moral and rhetorical paradigms that informed broader struggles for justice. The ethical obligation of other communities is to honor these contributions through acknowledgment, solidarity, and active engagement in dismantling ongoing inequities that continue to disproportionately affect African Americans. Such recognition is not symbolic alone; it requires the integration of ethical awareness into public policy, civic practice, education, and cultural representation, ensuring that African American contributions are neither erased nor taken for granted.

Quantitative and qualitative evidence underscores the material benefits of African American activism for other communities. Studies of employment integration and affirmative action reveal increased representation of Hispanic, Asian, Indian, and Arab Americans in professional sectors previously dominated by majority populations. Educational access initiatives modeled on African American desegregation campaigns facilitated higher enrollment rates and improved academic outcomes for diverse minority populations. Political engagement data indicate that voter registration strategies, legislative advocacy, and grassroots mobilization techniques derived from African American campaigns directly contributed to increased electoral participation among multiple marginalized groups.

Economically, union integration, anti-discrimination enforcement, and affirmative action policies expanded opportunities for business ownership, professional advancement, and labor protections across racial and ethnic lines. These measurable outcomes reflect the structural, practical, and enduring benefits of African American-led activism, reinforcing the moral imperative for recognition and respect.

Extended biographies of unsung activists further illuminate the pan-ethnic significance of the Civil Rights Movement. Septima Poinsette Clark’s citizenship schools empowered thousands of African Americans to participate politically while serving as a template for immigrant and Native American civic education programs. Ella Baker’s facilitation of grassroots organizing demonstrated the efficacy of decentralized leadership, influencing Arab American and Hispanic community organizing models.

Diane Nash’s coordination of Freedom Rides and sit-ins provided procedural and strategic paradigms subsequently adapted by Asian American student groups and Indian American civic organizations. The labor of these figures illustrates that African American activism was not merely instrumental for Black liberation, but foundational for multi-racial social transformation, reinforcing the ethical responsibility of other communities to demonstrate respect, acknowledgment, and gratitude.

Contemporary social movements continue to illustrate the enduring relevance of African American strategies and moral frameworks. Black Lives Matter, immigrant rights advocacy, Asian American anti-discrimination initiatives, Native American sovereignty campaigns, and Hispanic labor organizing all draw directly upon tactics, jurisprudence, and ethical paradigms pioneered during the Civil Rights era. Arab American and Indian American advocacy similarly employs coalition-building, legal intervention, and civic education strategies derived from African American precedent.

Recognition of these foundational contributions is essential, not only as an ethical acknowledgment of historical debt but as a practical guide for fostering cross-racial solidarity, sustaining civic engagement, and promoting equitable policy outcomes. Gratitude and respect, therefore, are inseparable from both historical justice and contemporary social efficacy, functioning as moral imperatives that reinforce the structural gains and ethical principles of African American-led activism.

In synthesizing the extensive regional, biographical, legal, educational, economic, cultural, and ethical dimensions of the Civil Rights Movement, it becomes incontrovertibly clear that African American leadership has provided both the practical and moral scaffolding upon which broader American social advancement has been constructed. Arab Americans, Indian Americans, Hispanic and Latino populations, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and marginalized Whites have all derived substantial benefits from African American struggle, yet ethical reflection demands that these communities recognize, honor, and actively support African American ancestry and contemporary citizenship.

The liberation, agency, and achievements of African Americans are neither merely historical artifacts nor abstract moral exemplars; they constitute the foundational infrastructure of equity, democracy, and justice from which all marginalized communities benefit. Ethical acknowledgment, sustained respect, and demonstrable gratitude are therefore not optional adjuncts to social participation but essential components of civic responsibility, historical literacy, and collective moral integrity. The Civil Rights Movement, in its strategic brilliance, ethical clarity, and operational efficacy, thus remains a living legacy, instructing all Americans that justice, solidarity, and gratitude are inseparably intertwined.

The legacy of the African American-led Civil Rights Movement is particularly evident when analyzed through regional, multi-ethnic case studies that demonstrate both the direct and indirect benefits accrued by other racial and ethnic communities. In the Southern United States, the epicenter of legal and extralegal oppression during the Jim Crow era, the strategic innovations developed by African American activists created templates for sustained civic engagement and structural reform. Hispanic and Latino communities in Texas and Louisiana, for instance, adapted African American voter registration techniques, civic education frameworks, and grassroots organizing strategies to challenge longstanding mechanisms of disenfranchisement, including restrictive literacy tests and gerrymandered districts. Empirical analyses indicate that counties in Texas where Hispanic organizers employed these methods saw measurable increases in voter registration and turnout rates over successive election cycles, paralleling patterns first achieved in African American communities through initiatives like Mississippi’s Freedom Summer. Beyond electoral engagement, these strategies facilitated enhanced representation in municipal councils, school boards, and labor unions, underscoring the structural benefits derived from African American activism.

Arab American populations in urban Southern centers, such as Birmingham and Atlanta, have similarly leveraged African American strategies in contesting discriminatory housing practices, employment inequities, and civil liberties violations. Legal interventions based on anti-discrimination jurisprudence established during the Civil Rights era, including Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States and subsequent housing equality litigation, have provided the structural framework for Arab Americans to secure equitable access to housing and employment.

Moreover, grassroots coalition-building, modeled on African American neighborhood organizing, has enabled these communities to influence city planning, educational policy, and civic infrastructure. Quantitative measures from urban policy studies indicate that neighborhoods with organized Arab American civic groups, employing African American-derived models, demonstrate higher rates of legal redress for housing discrimination and more equitable allocation of municipal resources, reflecting both procedural and substantive gains.

In Northern urban centers such as Chicago, Detroit, and New York, African American-led campaigns against de facto segregation in housing, schools, and labor markets generated procedural and strategic templates now utilized by Indian, Asian, and Hispanic communities. Indian American professional associations have adapted African American strategies for networking, mentorship, and advocacy to challenge discriminatory employment practices, particularly in STEM fields, legal professions, and higher education administration.

Asian American student organizations have employed methodologies derived from SNCC and CORE to contest discriminatory admissions, curriculum bias, and school resource inequities. Hispanic and Latino advocacy groups, drawing upon African American civil rights organizing principles, have successfully negotiated bilingual education programs, labor protections, and equitable school zoning, producing measurable improvements in graduation rates and academic achievement. These multi-ethnic adaptations demonstrate that African American-led strategies functioned not merely as historical interventions but as transferable operational and ethical paradigms, capable of generating systemic benefits across racial and ethnic lines.