Slavery in Iowa

The history of slavery in Iowa cannot be divorced from the broader national context, including the genocidal violence of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the forced marches of the Trail of Tears, and the mass exploitation of Black labor through the slavery industrial complex. Even as Iowa positioned itself on the right side of formal abolition, the mechanisms of white supremacy, racial capitalism, and institutional complicity laid deep roots in its soil.

In the early years of Iowa’s colonial and territorial formation, slavery was not widely practiced but was nonetheless present. Iowa became a part of the United States with the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and when settlers—many from Southern states—migrated into the region, they brought enslaved people with them. Though Iowa was later organized under the Missouri Compromise of 1820 as a free territory, individual slaveholders ignored the legal restrictions and maintained enslaved Africans in the region.

Historical records show that in Dubuque, for example, enslaved persons were held by Julien Dubuque himself, who operated lead mines and secured labor through arrangements with both Native tribes and enslaved African people. His reliance on slave labor—though technically informal—demonstrates that the slave economy had already penetrated Iowa before it was even a formal state.

As white settlers increasingly occupied Iowa’s lands, displacing Indigenous populations through treaties and military campaigns backed by federal policy, the economy began to take shape. The enslavement of African people was complemented by the forced removal and dispossession of Native peoples, particularly the Sauk and Meskwaki nations. This dual exploitation—of Black bodies through chattel slavery and of Indigenous lands through removal and genocide—formed the bedrock of Iowa’s agricultural and economic foundations. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 played a pivotal role in this history.

While often associated with the Deep South, the Act had far-reaching effects across the Midwest, including Iowa. Indigenous communities were violently forced to cede ancestral lands to make way for white settlers, who then developed those lands with the infrastructure and wealth generated by slavery in other regions. Though few slaves were sold or trafficked within Iowa itself, the state benefited economically from its role as a node in a national system that transferred capital, goods, and wealth from slaveholding states into emerging markets in the North and West.

Iowa officially entered the Union as a free state in 1846, but this designation belied the state’s growing participation in the slavery industrial complex. The prosperity of towns like Keokuk and Council Bluffs was directly linked to trade with slaveholding states and access to Mississippi River ports, where goods produced by enslaved labor—including cotton, tobacco, and sugar—were processed and redistributed. Iowa became a logistical partner in the infrastructure of slavery, supplying manufactured goods, livestock, and grains that were often exchanged for commodities harvested by enslaved people. Furthermore, Iowa’s banking institutions, railroads, and early industrial ventures invested in securities and enterprises that were tied to slavery-based profits. These financial entanglements meant that white Iowans profited from slavery even as they claimed moral superiority over their Southern counterparts.

The legacy of slave migration into and through Iowa also contributes to this history. Enslaved people seeking freedom through the Underground Railroad found both refuge and betrayal in Iowa. While some towns and communities in the state offered assistance to runaway slaves, others turned them over to slave catchers for bounty. Iowa’s proximity to Missouri, a slave state, placed it at the crossroads of freedom and captivity. Free Black residents in Iowa often lived under constant threat of violence, surveillance, and legal harassment. The state enacted Black Codes, including laws that prohibited Black people from testifying in court, owning property in certain areas, or marrying white individuals. These codes effectively extended the logic of slavery into Iowa’s so-called “free” society, criminalizing Black existence and restricting mobility, rights, and economic opportunity.

Iowa's universities and religious institutions were also complicit in the machinery of slavery. Early colleges such as the University of Iowa, founded in 1847, received donations and land grants from individuals and institutions who had profited directly from slavery. Some trustees and donors made fortunes from commerce with the South or from industries like textiles and insurance, which relied on slave-produced cotton and the underwriting of slave voyages. The University of Dubuque and other religiously affiliated colleges often failed to challenge the theological justifications for slavery, and many were silent on the moral atrocities being committed just across the border in Missouri. While some students and faculty participated in abolitionist movements, their impact was limited and often marginalized within institutional frameworks that prioritized economic growth over moral justice.

Following the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, the Freedmen’s Bureau sought to provide support for formerly enslaved people, but its presence in Iowa was minimal and largely symbolic. The state did not have a large population of freedmen, but it did receive Black migrants during Reconstruction and the Great Migration who sought better opportunities in the North. These Black Iowans faced systemic discrimination in housing, education, employment, and political participation. Segregated schools persisted well into the twentieth century, and Black residents were often confined to substandard neighborhoods without access to public services. While the absence of Jim Crow laws in name might suggest a more egalitarian society, Iowa practiced de facto segregation that was every bit as corrosive as the legally codified racism of the South.

The struggles of Black Iowans gave rise to a new generation of abolitionists, civil rights laborers, and freedom fighters who carried forward the unfinished work of emancipation. Notable among them was Alexander Clark, a prominent African American lawyer, diplomat, and civil rights advocate born in Pennsylvania but raised and politically active in Muscatine, Iowa. Clark successfully challenged the segregation of Iowa schools in the 1868 case Clark v. Board of Directors, which resulted in a landmark decision by the Iowa Supreme Court mandating integrated education. His work predated and anticipated Brown v. Board of Education by nearly a century, and his legacy is a powerful example of how Black Iowans fought tirelessly for justice even in supposedly free states.

Clark’s activism laid the foundation for subsequent movements, including the NAACP chapters established in Iowa cities like Des Moines and Davenport. During the Civil Rights Era, Black Iowans participated in national campaigns for voting rights, fair housing, and labor equality. The struggle often met with hostility from white residents who clung to the myth of racial innocence in the Midwest. Redlining, police brutality, and economic exclusion continued to define the Black experience in Iowa. These injustices were not anomalies but continuations of the structures first forged in the era of slavery.

The legacy of slavery in Iowa also resides in the institutions that continue to benefit from it. Many Iowa-based corporations, especially those in agriculture, finance, and insurance, have historical ties to slavery. Companies like Principal Financial Group, originally the Bankers Life Association, held investments linked to Southern plantations and insurers of slave property. Agricultural firms that dominate Iowa’s economy today rely on land that was originally expropriated from Indigenous peoples during the Trail of Tears and earlier military campaigns. The mass removal of Native nations from Iowa under the Indian Removal Act created the spatial and political conditions for large-scale agricultural exploitation—a legacy that continues in the present.

Iowa’s public and private universities have yet to fully reckon with their roles in this legacy. Endowments and property holdings can be traced to donations and land grants facilitated by slave profits or the displacement of Indigenous nations. Even today, Black faculty and students remain underrepresented and marginalized within these institutions. Cultural centers, African American studies programs, and diversity initiatives often face underfunding and political resistance. Reparative efforts, when undertaken at all, tend to be symbolic rather than structural, failing to address the deep economic and racial disparities that are slavery’s most enduring legacy.

Moreover, the very geography of Iowa—its cities, roads, and rivers—bears the imprint of forced migration. Though Iowa was not a site of the Trail of Tears in the conventional sense, it served as a corridor through which Native nations passed on their way to assigned reservations in Kansas and Oklahoma. The U.S. Army facilitated these removals with the same brutality and disregard for human life that characterized the institution of slavery. The genocide of Indigenous people in Iowa was necessary for the expansion of slavery and white settlement in the West, illustrating the convergence of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous violence within a single settler colonial framework.

To understand slavery in Iowa is to understand the profound interconnectedness of racial violence, economic development, and national mythology. Iowa’s reputation as a bastion of progressive values masks a far more complicated history, in which the state played a willing and active role in maintaining white supremacy. From the exploitation of enslaved African labor in the pre-statehood period to the complicity of banks, colleges, and corporations in the broader slavery industrial complex, Iowa is deeply implicated in the story of American slavery. The legacy of this history is not confined to the past but lives on in the structural inequalities, racial injustices, and institutional silences that define the present.

As the nation lurched toward the Civil War in the mid-19th century, Iowa found itself in an increasingly strategic position both geographically and politically. Bordered by Missouri to the south—a slave state—Iowa became an essential corridor in the struggle over freedom and bondage. The Missouri Compromise and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 further heightened tensions in the region, placing Iowa at the edge of bleeding borderlands. Iowa’s participation in the Underground Railroad was emblematic of its duality—its citizens included both brave abolitionists and treacherous bounty hunters. Clandestine routes snaked through rural counties and river towns, providing sanctuary for fugitive slaves, while others in the same communities reported runaways for monetary reward or due to allegiance to pro-slavery ideologies.

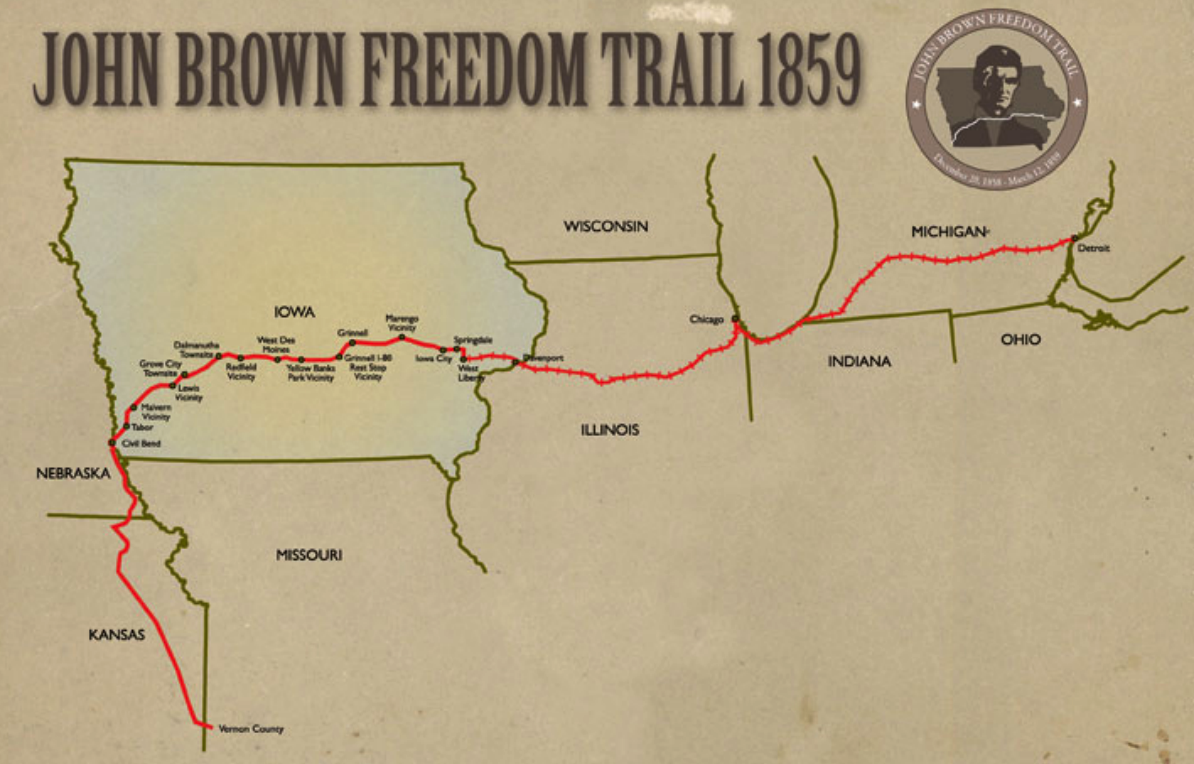

In the counties of Lee, Henry, and Johnson, local churches, Quaker communities, and Black settlements worked together to shelter escapees. Individuals like John Brown, though not Iowan by birth, found support and passage through Iowa as he planned militant resistance against slavery. Brown’s 1859 raid on Harpers Ferry was preceded by meetings and strategic stops in Iowa towns like Springdale, which hosted abolitionist Quakers and allowed him to train his raiders. Yet this sanctuary was often conditional and fragile. Black people who sought to settle in Iowa after escaping bondage were not always welcomed. Though Iowa did not formally criminalize Black residency as some other Northern states did, de facto racism shaped their daily lives. Segregated schooling, exclusion from land ownership, and labor discrimination were rampant.

During the Civil War, more than 75,000 Iowans enlisted to fight for the Union, and Iowa earned a reputation as a strong anti-slavery state. However, Black enlistment was initially resisted, and it was only after the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation that Black men were formally allowed to serve in the Union Army through regiments like the 60th United States Colored Infantry. Even so, they did not receive equal pay, were often relegated to the most dangerous tasks, and were subjected to abuse by white officers. After the war, many returning Black veterans faced compounded challenges. Having fought for a nation that still denied them full citizenship, they were subjected to economic exclusion and racial violence even in a state that claimed to be free.

One of the most harrowing aspects of slavery’s legacy in Iowa was its evolution into new forms after abolition. As Reconstruction policies failed to uproot the core of white supremacy, old power structures repackaged themselves through new mechanisms—vagrancy laws, convict leasing in nearby states, and economic coercion. Black Iowans were often denied employment in skilled trades and restricted to low-paying, unstable labor in agriculture and domestic service. The wealth gap created by centuries of unpaid labor was never addressed, and Iowa, like other Northern states, made no serious attempt at reparations. Instead, it erected subtle barriers that maintained the racial hierarchy. Labor unions often excluded Black workers, housing covenants restricted property access, and banks denied loans to Black applicants through redlining practices.

The growing industrialization of Iowa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries did little to benefit Black communities. Factories and railroads in cities like Cedar Rapids, Waterloo, and Des Moines offered employment but often refused to hire Black workers or placed them in the most dangerous, least compensated positions. White immigrants from Europe, including Germans, Norwegians, and Irish, were incorporated into the social and economic fabric of the state, given access to land and labor protections, while Black migrants from the South were treated as a permanent underclass. This created a stratified society in which whiteness conferred privilege and safety, regardless of one's economic condition, while Blackness was associated with risk and dispossession.

Higher education in Iowa, although touted as progressive, also reflected this racial exclusion. The University of Iowa did admit Black students earlier than many other institutions, but their experiences were marked by isolation and hostility. Dormitories, fraternities, and social clubs were largely closed to them, and Black faculty were virtually nonexistent until well into the 20th century. Similarly, other institutions such as Grinnell College and Drake University have benefited from endowments and land that originated in settler colonial acquisition, slave-derived wealth, or both. Though many of these institutions now acknowledge their histories in performative statements, few have committed to institutional reparations, scholarships, or curriculum changes that address their complicity in historical racism.

The political landscape of Iowa during Reconstruction and beyond also reflected the national betrayal of Black liberation. While Black men were technically granted the right to vote through the 15th Amendment, local practices of voter suppression abounded. Poll taxes, literacy requirements, and outright intimidation discouraged Black civic participation. In Iowa’s smaller towns and rural counties, Black voters were often the targets of harassment. Although Iowa was among the first states to ratify the 14th Amendment, affirming citizenship for freed slaves, the enforcement of these rights was weak and inconsistent. The machinery of justice—from local sheriffs to judges—was dominated by white men who had no commitment to racial equity.

The Great Migration, beginning around 1915, brought larger numbers of African Americans into Iowa from Southern states. They came fleeing lynching, tenant farming exploitation, and Jim Crow, seeking industrial jobs and better futures. Cities like Waterloo and Davenport became new centers of Black life in Iowa. However, the migrants found that Northern racism was just as debilitating as its Southern counterpart, albeit more insidious. Schools were segregated in practice, if not by law. Black families were forced into redlined neighborhoods, subjected to substandard housing, and denied public infrastructure. In places like Des Moines, entire Black neighborhoods were displaced by urban renewal projects, highways, and gentrification—a new wave of land theft under the guise of progress.

This systemic exclusion extended into every facet of life. Hospitals denied Black patients equal treatment, churches often remained racially segregated, and local newspapers ignored or misrepresented Black experiences. Policing also reflected the ongoing legacy of slave patrols, with Black residents disproportionately stopped, searched, and arrested. This surveillance culture was rooted in the same logic that had governed slave societies—the notion that Black freedom must be policed, constrained, and never fully realized.

Despite these oppressive conditions, Black Iowans continued to organize, resist, and dream. The legacy of resistance that began with escaped slaves and early abolitionists blossomed into vibrant community activism. Organizations like the Des Moines Urban League, founded in the early 20th century, provided vocational training, housing support, and legal aid for Black residents. Churches, often the only autonomous institutions Black Iowans could fully control, became centers of political education and organizing. Figures such as Edna Griffin, known as “the Rosa Parks of Iowa,” led sit-ins and protests against segregated lunch counters in the 1940s, years before similar acts would spark the Civil Rights Movement in the South.

The 1960s and 1970s saw renewed waves of protest, particularly on college campuses, where Black student unions demanded curriculum changes, faculty diversification, and cultural centers. In Iowa City, Black students at the University of Iowa led demonstrations that resulted in the establishment of an Afro-American Studies Program and cultural houses. In Waterloo, Black workers organized against discriminatory practices at meatpacking plants, demanding fair wages and union representation. These movements drew from the same well of resistance that had sustained enslaved Africans centuries before—an unbreakable spirit committed to justice and self-determination.

Yet even as these movements made gains, the structural legacy of slavery refused to yield. Iowa’s prison population began to swell in the late 20th century, reflecting a national trend of mass incarceration that disproportionately targeted Black communities. Drug laws, mandatory minimums, and aggressive policing strategies filled Iowa’s jails with Black bodies at rates wildly disproportionate to their share of the population. The Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery “except as punishment for a crime,” found new expression in the prison-industrial complex, where incarcerated labor was exploited and commodified. Black Iowans became the new face of penal labor, continuing a cycle of economic exploitation that dated back to slavery.

Even today, the economic indicators reveal staggering inequality. Black unemployment in Iowa is consistently more than double that of white Iowans. The racial wealth gap persists across generations, with white families owning homes, land, and financial assets at much higher rates. Educational attainment remains unequal, and Black children are suspended, expelled, and disciplined at far higher rates than their white peers in Iowa’s schools. These disparities are not accidental—they are the direct consequence of centuries of racialized policy, systemic theft, and legal exclusion rooted in the foundations of slavery.

Meanwhile, Iowa’s political climate in the 21st century has often tilted toward policies that exacerbate these inequalities. Voter ID laws, anti-critical race theory legislation, and attacks on diversity programs in universities all reflect a broader effort to whitewash history and silence the descendants of those who endured slavery’s horrors. The refusal to reckon honestly with the past ensures its continuation in the present. The myth of Iowa as an egalitarian, colorblind state is belied by its persistent racial gaps in health, income, education, and justice.

Amid these challenges, new generations of Black Iowans have continued to demand justice. The protests that erupted following the murder of George Floyd in neighboring Minnesota reverberated throughout Iowa’s cities and towns. In Des Moines, Iowa City, and Cedar Rapids, thousands marched, calling not only for police accountability but for a complete reimagining of public safety, economic justice, and racial equity. These movements are not new; they are the descendants of enslaved Africans, of freedmen who challenged exclusion, of veterans who fought wars abroad only to return to racism at home. They are the voices of the past refusing to be silenced in the present.

A full reckoning with slavery in Iowa requires more than commemoration. It demands reparation, structural transformation, and historical clarity. It demands that Iowa’s institutions—its colleges, its banks, its government agencies, its churches—admit their roles in this long and brutal history. It calls on them to not merely express regret but to return land, redistribute resources, and dismantle the structures of exclusion. The land upon which Iowa’s prosperity was built was stolen from Indigenous nations and cultivated through systems enriched by slavery. The wealth passed down in white families is, in many cases, derived from these acts of violence and exploitation. Recognition without redress is empty.

In Iowa today, there are opportunities to chart a new path, one rooted in truth and justice. Educational curricula can center the histories of Black and Indigenous peoples not as footnotes but as foundational narratives. Public monuments can be erected to honor Black abolitionists, enslaved persons who passed through Iowa seeking freedom, and Indigenous resistance fighters. Economic development programs can be tailored to rectify historical injustices, offering grants, loans, and property access to Black and Native communities. Universities can commit a portion of their endowments to fund reparative scholarships, research, and community partnerships. The government can issue formal apologies and establish commissions to study and implement reparations.

None of these acts can undo slavery’s horrors, but they can signal a moral awakening. Iowa has the opportunity to lead—not in erasing its past, but in illuminating it. By confronting the truth of its connections to slavery, the state can offer an example to others in how to move from denial to dignity, from exploitation to equity. The descendants of the enslaved and the dispossessed deserve not only remembrance but restoration. That restoration must begin with an honest appraisal of history, and a commitment to building a different kind of future.

The historical arc of slavery in Iowa, though often minimized or ignored in mainstream narratives, must be understood as an integral component of the American experiment in racial capitalism. Slavery in Iowa was not a peripheral institution, nor was Iowa merely a bystander in the nation’s project of white domination. From the early presence of enslaved labor under French and Spanish colonial arrangements to the deeply embedded complicity of Iowa’s industries, governments, and academic institutions in the slavery industrial complex, the state’s development was underwritten by anti-Black exploitation and Indigenous erasure.

Nowhere is the long shadow of slavery in Iowa more visible than in the economic structures that persist today. The legacy of intergenerational poverty among African Americans in Iowa is directly tied to the historical denial of land ownership, education, and financial credit. From the 19th century into the present, Black families in Iowa have faced compounding disadvantages, beginning with the inability to amass wealth through property—a key factor in the reproduction of middle-class status in America. White homesteaders in Iowa were granted massive land tracts under the Homestead Act, often on territory seized from Native peoples, while Black Americans were systematically denied access to these opportunities, even when they had served in the Civil War or relocated to Iowa seeking better prospects.

During the 20th century, this exclusion evolved through racist lending practices like redlining, where Black neighborhoods in cities such as Des Moines, Waterloo, and Davenport were deemed “high-risk” by banks and insurance companies, denying residents access to home loans, business capital, and flood or fire insurance. This discriminatory zoning and lending extended even to state-sponsored programs and federal housing assistance.

The GI Bill, for instance, was implemented in a racially exclusionary fashion, disproportionately benefiting white veterans. The result is that, even now, Black homeownership rates in Iowa lag far behind those of white residents, and wealth accumulation continues to favor white families who inherited assets from generations of advantage, many of which trace back to the profits of slavery or the seizure of Indigenous lands.

Equally significant is Iowa’s continued reliance on racialized labor. Throughout the 20th century, industrial employers across the state—particularly in meatpacking and agricultural processing—exploited Black labor under hazardous conditions with minimal pay and benefits. Black workers in these sectors were often brought in as strikebreakers or segregated into the most dangerous roles, a tactic that both exploited and divided working-class solidarity. This method of labor extraction reflects the afterlife of slavery: workers whose bodies are viewed as disposable, whose communities are surveilled and controlled, and whose contributions are systematically devalued.

The prison system in Iowa is also a site where the legacy of slavery takes on modern form. With the loophole in the Thirteenth Amendment permitting involuntary servitude as punishment for a crime, mass incarceration has become a mechanism for extracting labor and controlling Black populations. Iowa has among the highest Black-to-white incarceration disparities in the United States.

Black Iowans, who constitute less than 5% of the state population, make up nearly a quarter of its prison population. This is not merely the result of crime rates but of deliberate policy choices: racially biased policing, prosecutorial discretion, sentencing disparities, and mandatory minimums that disproportionately affect African Americans. Incarcerated individuals in Iowa are often required to perform unpaid or underpaid labor—cleaning, maintenance, and even agricultural work—which echoes the plantation model of coerced labor under violent supervision.

Education, too, bears the burden of this history. Despite formal integration, Iowa’s schools remain largely segregated by race and income. Majority-Black schools receive less funding, offer fewer Advanced Placement courses, and suffer from higher teacher turnover. Disciplinary practices disproportionately target Black students, leading to what is known as the “school-to-prison pipeline.”

This pattern of exclusion mirrors slavery’s educational legacy, in which literacy and knowledge acquisition were deliberately withheld from enslaved people as a mechanism of control. Even in Iowa’s universities, Black students report racial hostility, underrepresentation, and a lack of institutional support. The marginalization of African American history within the curriculum ensures that future generations remain unaware of slavery’s central role in the formation of their state. Iowa’s elite institutions of higher education continue to benefit from slave-linked wealth and land acquisition. The Morrill Act of 1862, which established land-grant colleges like Iowa State University, was financed through the sale of Native lands—often acquired through forced removals, broken treaties, or outright violence. This included parcels stolen during the federal government’s enforcement of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which paved the way for the Trail of Tears.

Though the most infamous marches occurred in the South, the logic of Indigenous removal permeated Iowa as well. Tribes such as the Meskwaki (Sac and Fox) were dispossessed, marginalized, and forced into remote reservations or out-of-state exile. While the Meskwaki people later repurchased land and rebuilt their community in Iowa, their story is one of extraordinary resilience in the face of genocidal policy—a policy that was inextricably linked to the expansion of slavery and settler colonial agriculture.

The convergence of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous violence in Iowa underlines a central truth: slavery and colonization were not parallel systems but mutually reinforcing processes. The land had to be cleared of Native peoples so that it could be tilled and harvested with enslaved labor or with white settlers who profited from the economy built by enslaved people. The state of Iowa did not escape this calculus; rather, it was one of its laboratories. As Iowa’s railroads expanded westward in the 19th century, many were funded by Northern investors whose portfolios included Southern plantations. Cotton from enslaved labor financed the steel rails, locomotives, and depots that facilitated Iowa’s economic rise.

Churches and religious organizations in Iowa also played roles in the moral laundering of slavery’s legacy. While some Christian denominations in Iowa supported abolition, others hedged their positions or sought reconciliation with slaveholders after the war, emphasizing national unity over racial justice. These churches benefited from tithes and contributions by wealthy donors whose fortunes derived from slavery, colonialism, or extractive labor. The theological ambivalence of these institutions extended beyond slavery to the broader question of white supremacy. While sermons decried sin, they often ignored the structural sins embedded in the society’s treatment of African and Indigenous peoples. Today, few of these churches have issued public confessions, conducted reparative research, or returned stolen resources.

Across Iowa’s landscape, the absence of monuments, museums, and public markers dedicated to slavery and Black resistance is deafening. The state’s commemorative landscape is filled with statues of white settlers, military generals, and political leaders, while Black abolitionists, educators, and labor organizers go unrecognized. This erasure is itself a continuation of slavery’s ideological project—to deny the full humanity, agency, and contributions of African Americans to the building of the state. There are no grand memorials in Iowa to enslaved people who passed through its lands on the Underground Railroad, nor are there significant public investments in preserving Black heritage sites. The amnesia is not accidental; it is cultivated.

Yet in the face of this erasure, Black Iowans continue to resist, remember, and rebuild. Community-based organizations like the African American Museum of Iowa, based in Cedar Rapids, have undertaken the vital work of documenting and preserving Black history in the state. Through exhibitions, oral histories, and educational programming, the museum challenges the dominant narrative that Iowa’s past is one of racial harmony and exceptionalism. It insists that the story of Iowa is incomplete without the voices of those who endured and resisted slavery, segregation, and systemic injustice.

Youth-led movements, especially in recent years, have also breathed new life into Iowa’s ongoing reckoning. Black Lives Matter chapters across the state have mobilized for policy change, school reform, and police accountability. These movements connect local injustices to national struggles, recognizing that what happened in Charleston, Minneapolis, or Louisville is not alien to Iowa’s own streets and prisons. Activists in Des Moines have successfully advocated for civilian review boards, mental health crisis teams, and the defunding of militarized police units. These victories, while incremental, signal the potential for transformational change rooted in community power.

To move forward, Iowa must embrace a reparative framework—one that does not merely acknowledge historical injustice but actively dismantles its contemporary manifestations. This includes establishing state-funded reparations commissions tasked with studying the economic impact of slavery and proposing direct remedies. It includes creating pathways for Black land ownership through subsidized land trusts, reforming criminal justice policy to reverse the carceral legacy of the Thirteenth Amendment, and overhauling education curricula to center Black and Indigenous perspectives. It includes investing in mental health services, maternal care, and environmental justice in Black communities that have borne the brunt of neglect for generations.

Iowa’s colleges and universities must also do more than perform symbolic gestures. They must conduct full audits of their historical ties to slavery and Indigenous dispossession, disclose those findings publicly, and create redress mechanisms—including free tuition for descendants of enslaved people, paid fellowships for Black scholars, and investment in community education hubs. These institutions have the resources and responsibility to lead in the transformation of memory into justice.

The state government can take meaningful steps as well. A formal apology for Iowa’s participation in the slavery industrial complex and Indigenous genocide should be accompanied by policy commitments. Legislative acts can establish land return programs for Native nations, guarantee voting access for Black and brown communities, and reform tax structures that disproportionately burden the poor. These are not utopian demands; they are necessary steps toward the restoration of dignity stolen by centuries of systemic violence.

The struggle to end slavery did not conclude with the Emancipation Proclamation or the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment. Its continuation is evident in the environmental toxins that disproportionately affect Black neighborhoods in Iowa, the wage gaps that leave Black workers earning significantly less than their white counterparts, and the schools that remain underfunded and segregated. These are not isolated problems—they are legacies. And legacies demand response.

In conclusion, Iowa’s relationship to slavery is not a distant or abstract one. It is immediate, intimate, and ongoing. From its earliest territorial days, when enslaved labor undergirded lead mining and river trade, to its entanglement in a national economy built on Black suffering, Iowa has never stood apart from the American institution of slavery. Its white residents benefited directly and indirectly, through land, labor, wealth, and policy. Its Black residents bore the weight of that history in their bodies, their families, and their futures. Yet they also rose, resisted, and rebuilt—crafting a legacy of courage that demands to be honored.

The task before Iowa is not to escape its past but to confront it with honesty, humility, and action. The state must commit to repair what has been broken, return what has been stolen, and renew what has been silenced. Only then can it move from a state shaped by slavery to one committed to true freedom. Only then can Iowa begin to fulfill the promise of justice not merely for some, but for all.

New France: Iowa Focus

The area that is now the American state of Iowa was part of New France when first settled by Europeans. As such, it was governed by its slavery laws. French settlers first brought African slaves into Upper Louisiana from Saint-Domingue around 1720 under the legal terms of the Code Noir, which defined the conditions of slavery in the French empire and restricted the activities of free Black persons.

At the time, nine hundred slaves lived in Upper Louisiana, as well as at least three hundred slaves the French took with them as they left for the lands west of the Mississippi River, including modern-day Iowa. The institution of slavery continued after Britain acquired the Illinois Country in 1763 following the French and Indian War.

In the 1840 United States census 16 enslaved people were recorded in Iowa Territory, all living in Dubuque County. Other sporadic accounts of slavery occurred in Iowa Territory; the only recorded slave sale occurred in 1841, when O. H. W. Stull, the Iowa territorial secretary, purchased an enslaved boy in Iowa City.

Slavery was outlawed in Iowa when it obtained statehood in 1846. In the years leading up to the Civil War, many Iowans became involved in the Underground Railroad, and famed abolitionist John Brown used Iowa as a base for his anti-slavery campaigns, 1856-1859.

The state of Iowa played a significant role during the American Civil War in providing food, supplies, troops and officers for the Union army.

It’s still surprising to many Iowans to learn that the state's earliest settlers played in important role in antislavery and Underground Railroad efforts in the years leading up to the Civil War.

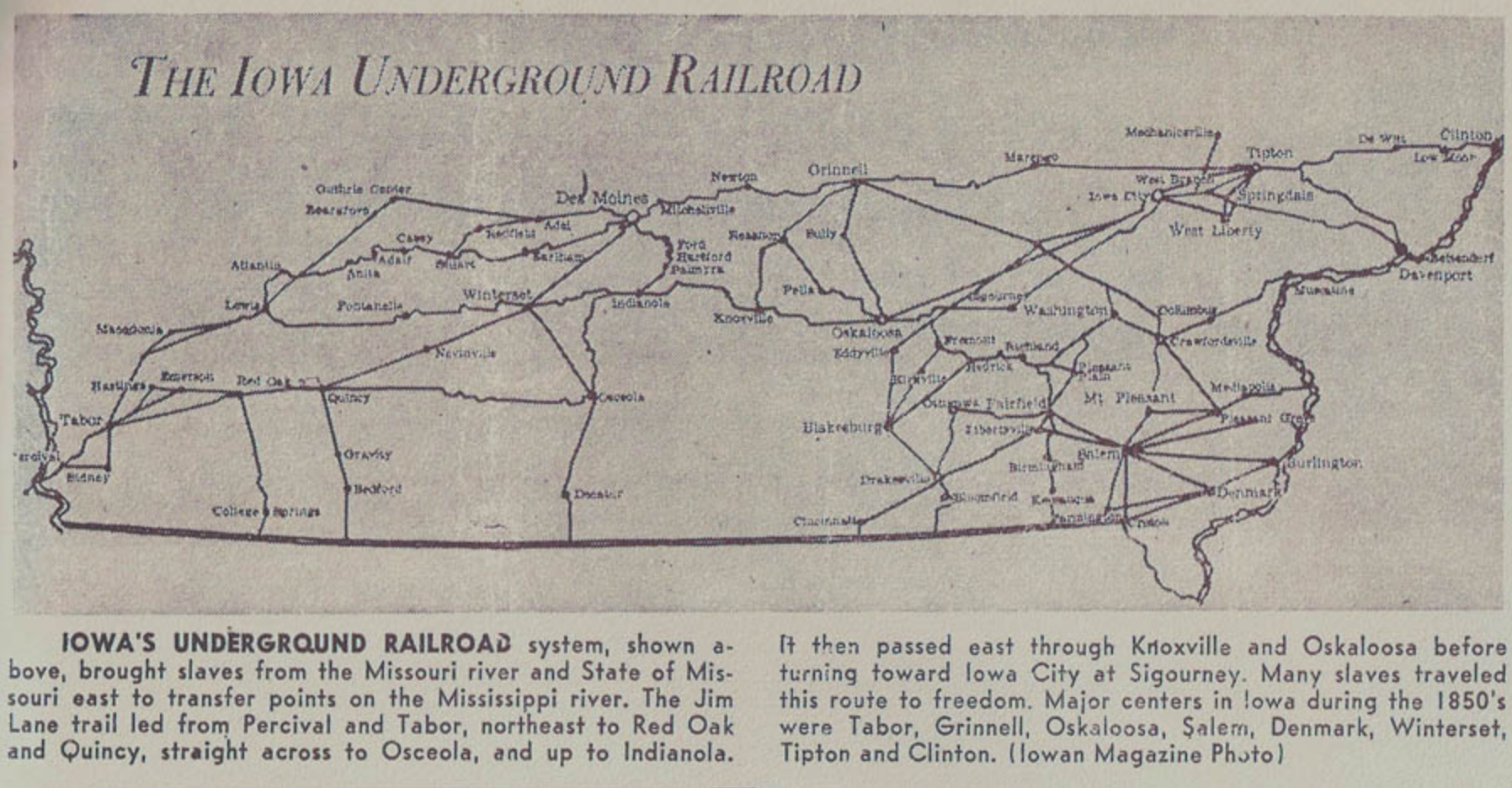

Though slaves were escaping and being helped to freedom from the early days of slavery in the United States, the phenomena known as the Underground Railroad lasted from about 1830 to 1861. Neither underground or an actual railroad, the term alluded to a loose network of sympathetic individuals and groups that were willing to risk life and liberty to help these fugitive slaves as they headed for the free states of the North and Canada.

Antislavery and underground railroad participants who operated north-of-the-border states knew Iowa as their westernmost free-state link. The risks of this already dangerous activity of helping escapees increased on September 18, 1850 when the United States Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. It required the United States government to aid in returning escaped slaves and punish those who hindered it.

Nevertheless, a number of Iowa's earliest settlers, often motivated by religious convictions and a marked appreciation of the principles of individual rights and personal liberty, provided shelter, transport, and material support for the travelers on this trail to freedom. The State Historical Society of Iowa conducted historical research and fieldwork through the Iowa Freedom Trail Project. This project sought to document Underground Railroad activities throughout Iowa by identifying individuals and groups who were involved with these activities and the places where these events occurred in Iowa.

The project continues to uncover new information, sometimes obtained from local sources and descendants of individuals involved in Underground Railroad activities.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad