Slavery in Florida

The history of slavery in Florida is a brutal yet essential chapter in the narrative of American oppression, empire-building, and resistance. Florida’s connection to slavery predates its admission as a U.S. state, stretching back to its earliest European colonization under Spanish control in the sixteenth century. While often overshadowed by the more well-known slavery narratives of the Deep South, Florida presents a complex tapestry where Indigenous genocide, African enslavement, and settler colonialism were woven tightly together to facilitate the rise of plantation capitalism and the modern corporate state.

Florida served not merely as a recipient of enslaved people but as an active agent in the violent circulation of Black labor, the exploitation of natural resources, and the construction of a racial caste system that continues to have economic and institutional legacies in the present day.

The earliest forms of slavery in Florida under Spanish control were defined by the encomienda system, a quasi-feudal labor regime imposed upon Indigenous populations such as the Timucua and Apalachee. However, with the decline of native populations due to disease and violence, Spanish colonizers turned increasingly to the importation of enslaved Africans. By the late seventeenth century, enslaved Africans were foundational to the economic activities of St. Augustine and the surrounding areas.

Notably, Florida was also a site of paradoxical refuge for escaped slaves from British colonies to the north. Under Spanish rule, runaways from Georgia and South Carolina who converted to Catholicism were sometimes granted freedom and protection. This tenuous sanctuary produced settlements such as Fort Mose, north of St. Augustine, which became the first legally sanctioned free Black community in what would become the United States. However, this relative haven was more exception than norm; as Florida changed colonial hands between Spain, Britain, and finally the United States, the fate of Black bodies was increasingly tied to the demands of white wealth accumulation and racial terror.

With the acquisition of Florida by the United States in 1821, the trajectory of slavery in the territory intensified and conformed to the plantation economy of the American South. Planters from Georgia, South Carolina, and Alabama migrated into Florida’s northern and central regions, bringing enslaved Africans with them. The soil and climate proved ideal for cotton, sugar, and tobacco production, and the enslaved workforce became the cornerstone of Florida’s agricultural boom. By the time of statehood in 1845, Florida was firmly entrenched within the slavery-driven cotton kingdom, with over 39,000 enslaved Black people making up nearly half of the population. Slaveholders held considerable political power, dominating the legislature, shaping laws that protected their interests, and crafting a legal environment in which slavery could expand unimpeded.

The economics of Florida’s slave system cannot be reduced merely to the cotton fields. The enslavement economy extended into maritime trades, timber industries, turpentine extraction, and cattle herding. Enslaved people worked in ports loading and unloading ships, they served as carpenters, blacksmiths, bricklayers, and domestic laborers in growing urban centers like Pensacola, Tallahassee, and Jacksonville. They built roads and canals and were hired out to state institutions for public works. This “hiring out” system created enormous profit margins for slave owners and further embedded slavery into the economic bloodstream of Florida’s developing industrial infrastructure. Wealth created by this coerced labor was not merely local; it was invested in banks, insurance companies, and shipping networks that enriched white families for generations.

With the spread of plantation agriculture came an increase in slave patrols, Black codes, and acts of state violence designed to suppress Black agency and prevent resistance. Enslaved people were routinely whipped, branded, mutilated, or lynched for minor infractions or suspected insubordination. Despite these repressive structures, Florida’s enslaved population resisted through work slowdowns, sabotage, escape, and revolt. The Second Seminole War, from 1835 to 1842, was in part driven by the U.S. government's desire to suppress maroon communities—groups of escaped enslaved Africans who had integrated into the Seminole Nation. These maroons and Black Seminoles fought tenaciously against U.S. troops, and their resistance complicated efforts to remove the Seminoles to Indian Territory.

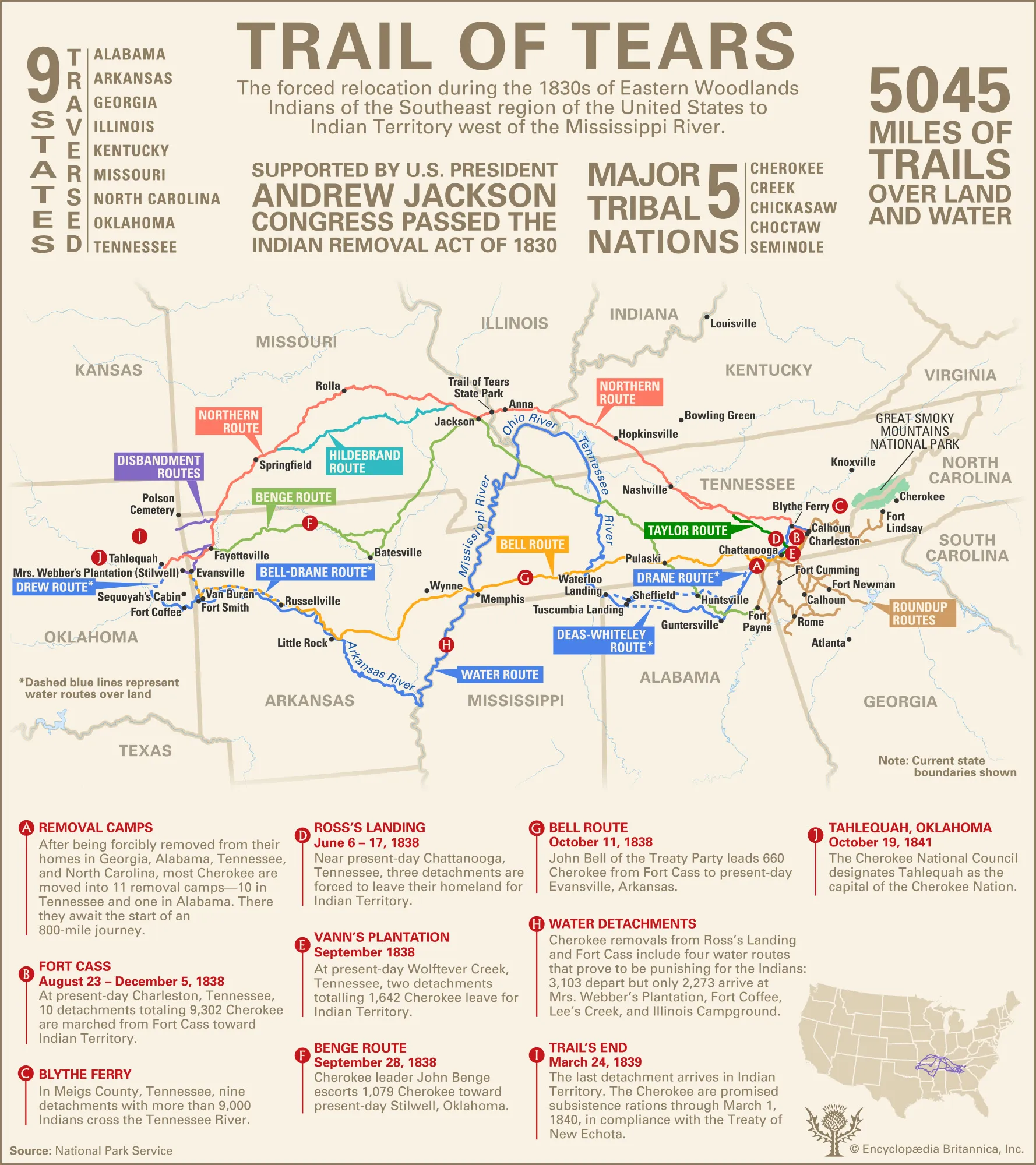

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was a pivotal piece of legislation that furthered the federal government’s commitment to clearing Indigenous land for white settler expansion and agricultural exploitation. For Florida, this meant not only the displacement of Indigenous peoples but also the rupture of Black communities that had coexisted or intermingled with them. The Trail of Tears—though often geographically associated with the Cherokee in Georgia and Tennessee—had direct implications for Florida. Seminoles, who included significant numbers of African-descended people, were hunted down, deported, and stripped of their land through brutal military campaigns. In this crucible of anti-Black and anti-Indigenous violence, slavery was not a side note but the central motive force. The drive to secure land for white-owned slave plantations was the linchpin of these genocidal policies.

The Civil War and eventual Union victory in 1865 brought legal abolition to Florida, but not economic or social liberation. The Freedmen’s Bureau was tasked with assisting newly emancipated African Americans, but in Florida—as elsewhere in the South—it was underfunded, understaffed, and frequently opposed by white politicians and former Confederates. Land was not redistributed. Education was undercut. Black testimony was often inadmissible in court. Many formerly enslaved people were forced into sharecropping arrangements or deceptive labor contracts that returned them to conditions perilously close to slavery. Vagrancy laws and convict leasing further criminalized Black existence and fed Black labor back into the capitalist system through state-sponsored incarceration. Florida's railroads, phosphate mines, and lumber companies all profited from convict leasing, which disproportionately targeted Black men and boys for trivial or fabricated offenses.

The structural legacies of slavery in Florida did not dissipate with Reconstruction’s collapse; they merely adapted to new legal, cultural, and economic frameworks. Institutions that benefited from slavery and white supremacy in the nineteenth century continued to build wealth and influence throughout the twentieth century. Corporations like Florida East Coast Railway, the United Fruit Company, and others relied heavily on Black labor with little to no protections. Banks and insurance companies that once underwrote slaveholders’ property now transitioned into modern financial entities that continued to profit from racial inequality. Real estate covenants, redlining, and disenfranchisement restricted the economic mobility of Black Floridians for generations.

Florida’s institutions of higher education were not innocent bystanders to these systems of oppression. Universities like the University of Florida, Florida State University, and the University of Miami trace their early endowments, trustees, or construction labor to ties with slavery or segregationist wealth. Some buildings were erected with funds generated through the exploitation of Black labor or with the use of Black convict workers. Scholarships, academic chairs, and research institutions were historically closed to Black Floridians, while some colleges offered their platforms to pseudoscientific racial theories that further entrenched white supremacy. Today, while some of these universities have begun to acknowledge this past, many have not fully reckoned with the economic advantages they gained from these morally bankrupt foundations.

Yet amid all this, there were always those who resisted, who sought to abolish slavery and uplift Black life. Florida was home to a number of Black abolitionists, preachers, and community organizers who laid the foundation for civil rights struggles in the twentieth century. Individuals such as John Wallace, a former enslaved person turned legislator; Mary McLeod Bethune, the educator and founder of Bethune-Cookman University; and A. Philip Randolph, a labor organizer and civil rights leader born in Crescent City, stand as towering figures in the legacy of Black liberation. These freedom fighters built schools, led voter registration drives, formed mutual aid societies, and organized labor unions—all in the face of lynch mobs, white terror, and state repression.

Civil rights laborers in Florida endured police brutality, bombings, and economic retaliation throughout the Jim Crow era. From the Tallahassee Bus Boycott in 1956 to the Black student movements of the 1960s and 70s, Florida remained a contested battleground for Black freedom. Activists fought for desegregation, educational equity, and political representation. Many paid with their lives. Others were jailed, fired, or disappeared. But through their efforts, they carved space for future generations to thrive.

Even now, the legacy of slavery haunts Florida’s legal system, public institutions, and corporate hierarchies. Disparities in income, incarceration, education, and health care are not coincidental—they are the enduring consequences of centuries of enslavement, racial capitalism, and state-sanctioned neglect. White-owned corporations that once insured slave ships or sold goods harvested by slave labor are now Fortune 500 entities. Universities built on land taken from Indigenous people and erected by Black workers remain central nodes in the Florida economy. Tourism and real estate empires that trace their roots to plantations or slave-built ports continue to profit while communities of color are displaced, underpaid, and overpoliced.

The state of Florida, like the nation, has not completed the work of repair. Formal apologies, historical markers, and partial reparations are inadequate substitutes for full reckoning and justice. True repair requires structural transformation—redistribution of resources, institutional accountability, land restitution, and a radical reshaping of how history is taught, remembered, and embodied in law and policy.

The post-Emancipation era in Florida was one of deep contradictions. Although slavery had been legally abolished, the political, social, and economic structures that defined white supremacy were immediately reconstituted to maintain control over the newly freed Black population. Florida, like other Southern states, was quick to enact a series of Black Codes that aimed to restrict the freedom of African Americans and compel them to work in a labor economy based on low wages and debt. These laws criminalized Black mobility, banned vagrancy, prohibited firearm possession, restricted jury service, and enforced labor contracts that mirrored the obligations and punishments of slavery. Freed people who sought independence were met with violence, surveillance, and systemic economic sabotage.

As the Reconstruction period waned, Florida witnessed the rise of the convict leasing system—perhaps the most gruesome reincarnation of slavery under another name. This system allowed the state to lease out prisoners, most of whom were Black men arrested on false or minor charges, to private industries for labor. Florida was among the most brutal enforcers of convict leasing, and the violence visited upon leased convicts was staggering. They were whipped, starved, overworked, and left to die from disease or injury without medical attention. Corporations and white planters profited immensely from this coerced labor, while the state’s coffers filled with revenue generated by the exploitation of Black bodies.

Industries that built Florida’s infrastructure—railroads, phosphate mining, turpentine harvesting, and road construction—were dependent upon this pool of disposable Black labor. The turpentine industry, particularly dominant in North Florida, became notorious for its exploitation of Black workers. Enslaved people had once worked in this trade before emancipation, and after freedom, freedmen were trapped in debt peonage and violent labor camps where beatings and lynchings were common. Similarly, the expansion of rail lines under magnates like Henry Flagler and Henry Plant was made possible by Black workers who were underpaid, overworked, and often placed in dangerous conditions. The physical bones of Florida’s modern economy were laid by hands that received no compensation, recognition, or inheritance.

This structure of disenfranchisement persisted through the early twentieth century. Florida’s political machinery, backed by white vigilante violence and legal suppression, ensured that Black voters were excluded from democratic participation. Literacy tests, poll taxes, whites-only primaries, and grandfather clauses combined to disenfranchise the Black electorate. Simultaneously, white supremacist terror organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan and local posses committed acts of racial violence to maintain dominance. Towns like Rosewood and Ocoee became infamous not just for the massacres that took place but for the state’s complicity in erasing the Black presence that had once thrived there. The destruction of Rosewood in 1923, where a prosperous Black community was obliterated by a white mob, remains one of the most striking examples of racialized economic sabotage and collective trauma in Florida’s history.

Meanwhile, Black communities struggled to establish schools, churches, mutual aid societies, and business districts. With almost no support from the state, Black Floridians relied on collective strength and religious institutions to foster education and economic resilience. Churches played central roles in civil rights organizing, voter registration efforts, and mutual support systems. Despite repression, Black Floridians produced a generation of leaders, educators, and intellectuals who would become key figures in the national Black freedom struggle.

One of the most pivotal figures to emerge from Florida was Mary McLeod Bethune, born to former slaves in Mayesville, South Carolina but whose greatest work was accomplished in Daytona Beach, Florida. Bethune founded the Daytona Educational and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls in 1904, which later became Bethune-Cookman University. She was a relentless advocate for education as the primary vehicle for liberation and served as an advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Her legacy is a testament to the power of Black women’s leadership in a state that otherwise attempted to strangle every form of Black autonomy.

Florida also gave rise to A. Philip Randolph, the renowned labor organizer born in Crescent City. Randolph became the founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African-American labor union, and played a leading role in organizing the March on Washington Movement. Randolph’s insistence on economic justice as a cornerstone of civil rights forced the federal government to reckon with the exploitation of Black labor. His activism was grounded in the knowledge that the roots of America’s prosperity lay in stolen labor—an understanding shaped by his upbringing in a state where exploitation was omnipresent.

The civil rights movement in Florida accelerated during the 1950s and 60s. Protests erupted in Tallahassee, Miami, St. Augustine, and elsewhere. In Tallahassee, the 1956 bus boycott led by Reverend C.K. Steele became a model for nonviolent resistance in the South. College students, particularly from Florida A&M University, organized sit-ins, marches, and voter registration drives despite intimidation and violence. In St. Augustine, Martin Luther King Jr. and other leaders staged protests that drew national attention to Florida’s virulent racism. The backlash was fierce; local white mobs, often with police collusion, responded with beatings, arrests, and economic reprisals.

The passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 brought some legal changes, but the lived realities of Black Floridians often remained marked by inequality, police violence, and economic disparity. Integration was resisted, public housing was underfunded, and educational disparities persisted. Black communities continued to suffer from disinvestment and over-policing. The war on drugs in the 1980s and 1990s intensified mass incarceration, with Florida’s prison population—disproportionately Black—skyrocketing as private prison corporations profited from state contracts.

Modern corporations and colleges in Florida have also benefited—either directly or indirectly—from the legacy of slavery. Real estate developers profited from land originally granted to or acquired by wealthy planters who enslaved Africans. Companies like Florida Power & Light, Publix Super Markets, and the citrus industry benefited from discriminatory labor practices that trace their roots to plantation management. These institutions inherited wealth from generational white privilege built during and after slavery, often investing that wealth into modern economic empires without acknowledging the origins of their capital.

Florida’s public and private universities are deeply entangled in this history. The University of Florida, founded in the post-Reconstruction era, sits on land originally acquired through displacements of both Indigenous peoples and Black Floridians. Its early benefactors included politicians and businessmen tied to slavery, segregation, and forced labor systems. Florida State University, whose predecessors were developed with tax dollars that came from plantation profits, has recently begun exploring its ties to slavery, but many acknowledgments remain surface-level. While some universities have created task forces to examine their historical relationships to slavery, reparative justice has been minimal.

The erasure of Black labor and resistance from Florida’s historical narrative is itself a form of ongoing violence. Textbooks and public monuments in the state have long ignored or whitewashed the brutal realities of slavery and its enduring consequences. The state has often resisted efforts to mandate comprehensive Black history education. In recent years, political efforts have even sought to limit the discussion of race and slavery in schools under the guise of protecting students from discomfort. This historical sanitization continues the legacy of anti-Black suppression that slavery inaugurated.

Despite this, Florida remains a site of rich Black memory and culture. Descendants of enslaved people maintain traditions, preserve oral histories, and advocate for justice. Gullah-Geechee communities along the coast retain linguistic and cultural practices tied to West African heritage. Juneteenth celebrations, Black heritage festivals, and community restoration projects push back against erasure. Historical sites such as Kingsley Plantation, the African American Cemetery in Tallahassee, and Fort Mose now serve as living reminders of a history that has too often been buried.

The legacy of the Trail of Tears and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 is likewise present in Florida’s landscape. The Seminole people, both Indigenous and African-descended, resisted removal with bravery and fortitude. Black Seminoles in particular found themselves doubly targeted by federal troops and white settlers who viewed their autonomy as an existential threat. These communities were scattered, imprisoned, or deported to Oklahoma, where new forms of racial hierarchy awaited them. Yet resistance endured. The legacy of the Black Seminoles lives on in oral tradition, cultural memory, and sporadic legal efforts to reclaim tribal recognition and land rights.

This convergence of Indigenous and African struggle against a settler colonial state intent on genocide and enslavement forms the heart of Florida’s true history. The forced migrations of Native peoples and the enslavement of Africans were not parallel atrocities—they were part of a single system of land theft, labor extraction, and racial caste construction designed to feed the expansion of white wealth. Florida was not merely a site of these processes; it was one of their central laboratories.

In recent years, efforts have emerged to reckon with this legacy. Community organizations, scholars, and activists have begun to demand that Florida institutions conduct full audits of their historical ties to slavery, return land unjustly acquired, provide reparative scholarships, and invest in the communities built by the descendants of enslaved people. These efforts face strong opposition, yet they represent a necessary moral confrontation with a past that is not over but living still in the disparities of the present.

The case for reparations in Florida is not abstract or ideological—it is rooted in concrete histories of theft, brutality, and exclusion. It demands accountability not just from the state but from corporations, universities, churches, and media organizations that have profited from Black death and silence. Reparations would mean material resources for Black education, housing, healthcare, and business development. It would mean rewriting curricula, renaming buildings, restoring land, and above all else, listening to the voices that Florida tried for centuries to suppress.

The story of slavery in Florida is thus not a closed chapter but a continuing wound. It is a legacy etched into the soil, into the prison walls, into the debt burdens of Black families, into the underfunded schools, and into the erased names of those who labored, resisted, and died. To tell this story in its fullness is not only an act of historical honesty—it is a demand for justice. The plantation fields may have been replaced by gated communities, luxury hotels, and theme parks, but the ghosts of slavery remain. They cry out not only for memory but for repair.

As the twenty-first century unfolded, the deeper entrenchment of systemic racism in Florida became increasingly visible in both overt and covert forms. Though the formal structures of chattel slavery had been dismantled over a century before, their economic, psychological, political, and cultural shadows continued to dictate the lived experiences of Florida’s Black population. From the housing crises in cities like Miami and Tampa to the hyper-policing of Black youth, every major institution in the state bore the marks of the slave system’s legacy. The cycles of exclusion, extraction, and exploitation, shaped by the plantation regime, simply evolved into more palatable legal and social frameworks.

One of the clearest indicators of the continuity of slavery’s legacy in Florida has been the carceral system. Florida has one of the largest prison populations in the United States, with a disproportionately high number of incarcerated Black men. A state that once used the convict leasing system to extract profit from Black labor found new life in the private prison industry. Corporations such as GEO Group and CoreCivic, both with major operations in Florida, have profited from mass incarceration, exploiting prison labor, receiving state contracts, and reaping benefits from policies that criminalize poverty and Blackness. Prisoners are often paid pennies per hour for their labor, if anything at all, and are made to work in conditions not dissimilar from antebellum slavery. These practices include manufacturing goods, cleaning state facilities, farming, and more—all under threat of punishment and without labor protections.

In education, the scars of Florida’s racial history are equally apparent. Public schools serving predominantly Black communities are frequently underfunded, overcrowded, and staffed with fewer resources than those serving white or affluent neighborhoods. This discrepancy is a direct consequence of policies dating back to the post-Reconstruction era, when access to education for formerly enslaved people was systematically obstructed. In many ways, the state’s education system remains segregated by class and race. School districts with the highest concentrations of Black students often correlate with the poorest performance metrics and the lowest funding allocations.

In recent years, there has been growing political resistance in Florida to even teaching the complete history of slavery and racism. Legislation and administrative directives have been enacted to limit discussions of race, gender, and American history in K-12 classrooms and public universities. These measures have been justified by some political leaders under the guise of combating “divisiveness” or promoting “patriotic education,” but in practice, they perpetuate the historical silencing of slavery’s brutal reality and its long-term consequences. Such acts of institutional censorship are themselves extensions of slavery’s ideological infrastructure—designed to obscure the truth, delegitimize the voices of descendants, and maintain the myth of white innocence.

Meanwhile, economic disparities between Black and white Floridians reflect generations of stolen wealth. Median household incomes for Black families in Florida consistently lag behind those of white families. Wealth gaps, gaps in home ownership, and employment disparities reveal that economic mobility remains structurally obstructed. These inequities are not coincidental—they are directly traceable to centuries of unpaid labor, denied education, exclusion from New Deal housing policies, racially motivated zoning laws, and the ongoing effects of employment discrimination. Plantation wealth built in the nineteenth century transformed into financial and political capital in the twentieth and twenty-first. This capital was rarely redistributed but instead accumulated through inheritance, policy preferences, and institutional favoritism.

Some of Florida’s most recognizable industries—including agriculture, tourism, and real estate—trace their foundations to the slave economy. The citrus industry, which dominates Florida’s agricultural exports, was built on land worked by enslaved Africans and later by underpaid and exploited Black laborers. After emancipation, Black workers remained trapped in cycles of agricultural debt and seasonal employment. Their children, lacking access to quality education and job opportunities, often inherited these burdens. Even today, Black and Brown migrant workers face brutal working conditions, little legal protection, and economic precarity in Florida’s fields.

The tourism industry, now central to the state’s global brand, developed in part through land acquisitions and infrastructural developments funded by wealth rooted in slavery. Developers like Henry Flagler and Henry Plant did not simply build railroads and hotels; they built networks of power that excluded Black residents, denied Black laborers a share of the wealth they helped generate, and constructed racialized geographies. Flagler’s resort towns were explicitly designed to cater to wealthy whites while pushing Black workers to the periphery, often into unincorporated settlements with no public services. These workers were essential to the functioning of the tourism economy but were invisible in its public narratives.

Similarly, Florida’s real estate industry benefited from the confiscation of Black land and the use of racial covenants that forbade the sale of homes to African Americans. Redlining, predatory lending, and discriminatory zoning policies ensured that Black families were denied access to generational wealth through home ownership. Entire Black neighborhoods were destroyed or displaced in the name of urban development, often to make way for highways, stadiums, or commercial districts. In cities like Miami, Overtown was a thriving Black community before it was systematically dismantled. Today, gentrification continues this process under new names and new mechanisms.

The religious landscape of Florida also reflects the complexity of slavery’s enduring impact. Churches were central to both the spiritual survival and political organization of enslaved and freed Black people. During slavery, many plantation owners required their enslaved workers to attend white-controlled churches where messages of obedience and divine hierarchy were emphasized. Yet within these imposed religious spaces, enslaved people forged their own spiritual interpretations—blending Christian texts with African traditions, drawing strength from stories of liberation like the Exodus, and creating coded songs that communicated hope and resistance.

After emancipation, Black churches in Florida became powerful sites of resilience, education, and activism. They served as community centers, schools, meeting places, and headquarters for civil rights organizing. Baptist and African Methodist Episcopal churches, in particular, were instrumental in forming the backbone of Black political consciousness. Ministers were often among the few literate leaders in Black communities and played key roles in voter registration drives, mutual aid efforts, and moral resistance to injustice. This tradition persists into the present, with Black clergy in Florida continuing to lead struggles against police violence, voter suppression, and economic exploitation.

Slave narratives from Florida offer an irreplaceable window into the human cost of the state’s slave economy. Collected during the 1930s by the Federal Writers’ Project under the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, these testimonies are invaluable records of memory, pain, resilience, and truth. In their own words, formerly enslaved Floridians described the beatings, family separations, hunger, sexual violence, and spiritual endurance that defined their lives. These accounts are not simply historical documents—they are living indictments of a society that turned human beings into property, and they carry warnings and wisdom for future generations.

Among the narratives are stories like that of Henry Lowry of Jacksonville, who spoke of being sold at a slave market and remembered the trauma of seeing his mother whipped for attempting to protect her child. Others recalled the joy of emancipation, the confusion that followed, and the crushing disappointment of broken promises during Reconstruction. These voices, though often ignored in formal curricula, represent the moral conscience of the nation. They are testimonies not only of suffering but also of strength, endurance, and humanity in the face of dehumanization.

The Freedmen’s Bureau attempted to address some of the needs of these newly freed individuals, but its reach in Florida was limited. Bureau agents were often overwhelmed, outnumbered, and under constant threat from hostile white populations. Schools established by the Bureau faced frequent attacks. Attempts to redistribute land were undermined by political maneuvering and outright theft. Even so, the Bureau helped lay the groundwork for Florida’s first Black-led schools, churches, and civic organizations. Its legacy is a testament to the possibility and fragility of federal intervention in the cause of Black liberation.

Even in the face of unyielding resistance, Black Floridians continued to build. They formed business leagues, professional associations, literary societies, and fraternal orders. The Negro Business League of Florida promoted Black entrepreneurship in the early twentieth century. Educators like James Weldon Johnson—born in Jacksonville—wrote, taught, organized, and fought for dignity. Johnson’s hymn, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” composed with his brother Rosamond, has become the Black national anthem. It emerged from Florida’s soil, from its struggle, and from its dreams of a future not governed by white supremacy.

Today, the struggle continues. Florida has become a battleground for voting rights, criminal justice reform, and educational equity. Recent efforts to restore voting rights to formerly incarcerated individuals have met fierce resistance, despite the overwhelming support for Amendment 4, which aimed to re-enfranchise hundreds of thousands of citizens. State authorities implemented financial requirements and administrative hurdles that essentially created a modern-day poll tax, blocking the will of the voters and suppressing the political power of Black communities.

Grassroots organizations continue to fight against these structural injustices. Groups like the Dream Defenders, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition, and local chapters of the NAACP and Black Lives Matter work to confront the prison-industrial complex, demand affordable housing, expose environmental racism, and resist state-sanctioned censorship of history and identity. These movements are the direct descendants of the resistance forged in bondage, carried through Reconstruction, refined during Jim Crow, and sharpened in the crucibles of urban uprisings and rural resilience.

The future of Florida’s reckoning with its slave past depends on its willingness to engage with historical truth, invest in reparative policies, and center the voices of those long silenced. It requires a transformation of institutions, not just their rebranding. It calls for equitable education, economic justice, land restoration, and the dismantling of systems of surveillance and punishment rooted in slavery. It demands that those who profited from stolen labor—whether through inheritance, policy, or silence—participate in a new social contract based not on denial, but on dignity and accountability.

Florida’s soil is soaked in the blood, sweat, and tears of the enslaved. It is fertilized by their hopes, their dreams, and their resistance. From the rice fields of the Panhandle to the sugar plantations of the Everglades, from the urban corridors of Jacksonville to the maroon settlements of the swamps, the evidence is everywhere. The task now is not merely to remember, but to act.

Slavery in Florida was never only about unpaid labor or racial domination—it was about power, about wealth accumulation, about the construction of a political economy in which Black people could be commodified, dehumanized, and erased. That economy evolved, its methods transformed, but its essential structure remains visible. Today’s land development companies that convert historically Black neighborhoods into tourist zones, luxury condos, or gentrified commercial strips are following a familiar logic: extract, displace, profit, forget. It is a continuation of the logic of the plantation.

Florida’s wealthiest families and most influential developers have often remained silent or dismissive of their ties to this legacy. Yet property records, genealogies, business charters, and foundation endowments trace uninterrupted lines from plantation-era profiteering to modern real estate empires, banks, and corporations. The Mizell family in Fort Lauderdale, the DuPont descendants, and the powerful Flagler heirs are just a few examples of family dynasties built on the literal backs of enslaved laborers, which then expanded that wealth through investments, political lobbying, and land acquisitions that excluded Black Floridians at every step.

Major tourism destinations, including Walt Disney World and Universal Studios, while not directly involved in slavery, benefit from public subsidies, land policies, and economic models that continue to marginalize Black and Indigenous communities. The Disney corporation’s expansion into Central Florida involved complex land deals, massive tax breaks, and the transformation of entire landscapes. In some cases, Black towns and historically Black communities saw property values rise beyond affordability, leading to displacement and erasure. This modern displacement, cloaked in the language of progress and development, mirrors the forced removals of Indigenous and Black people in earlier centuries. It is not a new story; it is an evolved one.

The higher education system, likewise, holds both the burden and the possibility of addressing historical wrongs. Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU), established in 1887, remains the state’s only public historically Black university and has played a vital role in cultivating Black leadership. Yet it has historically received less funding than predominantly white institutions like the University of Florida and Florida State University, despite serving a population with greater economic needs. The underfunding of HBCUs is a national crisis, but in Florida, it takes on a particularly sharp edge given the state's history of systemic exclusion. The very state that used enslaved labor to build its infrastructure has failed to equally invest in the education of those laborers’ descendants.

Across Florida, grassroots efforts have emerged to preserve and protect Black heritage. Organizations like the Rosewood Heritage Foundation, the Gullah-Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission, and local Black history museums are working tirelessly to recover what was stolen—not only land and labor but also memory, dignity, and truth. These groups have undertaken oral history projects, preservation of ancestral burial grounds, public advocacy for curriculum reform, and campaigns for state and local reparations. Their work is often underfunded and politically targeted, yet it is essential. Without preservation, there is no foundation for justice.

Among the most egregious aspects of Florida’s racial legacy is the targeting and policing of Black youth. The school-to-prison pipeline in Florida has functioned with brutal efficiency. Black children are suspended, expelled, and arrested at far higher rates than their white peers for the same infractions. Zero-tolerance policies, school resource officers, and surveillance in low-income school districts create an environment of criminalization rather than support. This is a modern extension of the same systems that criminalized enslaved people for reading, for running away, for resisting, for simply existing without a white person’s permission.

Florida’s stand-your-ground laws and its history of racialized violence further illustrate how law is weaponized to protect whiteness and punish Blackness. The murders of Black men and boys like Trayvon Martin have highlighted the deeply racialized dimensions of Florida's legal system, where the presumption of guilt often falls along color lines. The killing of Trayvon Martin in Sanford in 2012 sparked a national movement, yet within Florida, it exposed how deeply ingrained racist assumptions are in public perception, law enforcement, and the judiciary. These assumptions are not recent—they are built on centuries of dehumanization that began with slavery.

The environmental dimensions of racial injustice in Florida are also worth noting. Historically Black neighborhoods and rural Black communities often bear the brunt of environmental hazards—industrial waste, polluted water, and lack of green spaces. These communities are often located near factories, highways, and toxic waste sites, a phenomenon known as environmental racism. The same logic that viewed enslaved people as expendable labor has viewed their descendants as expendable residents. Cleanup efforts are slow, accountability is rare, and reparative investment is almost nonexistent.

The stories of resistance in Florida, however, shine just as brightly as the injustices they oppose. The Tallahassee Bus Boycott, led by Reverend C.K. Steele and student leaders at Florida A&M, lasted longer than the more well-known Montgomery Bus Boycott and played a central role in building the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The students who organized sit-ins at Woolworth’s counters, who marched through police batons and tear gas, who registered voters under threat of death—these are the inheritors of the maroons who fought in the swamps, the Black Seminoles who resisted deportation, the enslaved people who taught each other to read in secret.

Their legacy is not simply resistance but radical love—a belief that justice is possible, that truth matters, that the future can be different. Today’s activists in Florida, many of them young, queer, Black, undocumented, or formerly incarcerated, are writing a new chapter in this history. They are reclaiming the language of abolition—not just of prisons, but of the economic, educational, and political structures that have perpetuated slavery by another name.

The Indian Removal Act of 1830, and the subsequent Trail of Tears, remains one of the most violent and consequential policies in Florida’s history. Although commonly associated with the Cherokee and the Southeastern United States, its full scope included the Seminole and their Black allies. The Seminole Wars—particularly the Second Seminole War—represented one of the most costly and prolonged conflicts fought on American soil. At the heart of this war was not only the U.S. military’s desire to relocate Native peoples but also the fear of autonomous Black communities. The presence of Black Seminoles, who had escaped slavery and forged bonds of kinship and solidarity with the Seminole Nation, challenged the foundations of the slave-holding society. Their very existence was a threat to the order that white Florida sought to establish. The Trail of Tears did not just remove people from their land; it severed intergenerational continuity, destroyed economies, and attempted to erase cultures. Those who survived faced new systems of containment and marginalization in the Indian Territory, now Oklahoma. Their descendants, both Indigenous and Black, remain engaged in battles for recognition, sovereignty, and reparations. Florida has yet to adequately memorialize this history. Few monuments, few state-mandated curricula, and even fewer public acknowledgments exist to confront this violent past.

Slavery in Florida was not an anomaly. It was central to the state’s founding, development, and modern prosperity. The profits of slavery built banks, universities, roads, ports, and political careers. Its ideology shaped laws, culture, and institutions. Its aftershocks are present in the racial wealth gap, in segregated schools, in disproportionate health outcomes, and in the stories of families still seeking justice for stolen land and lost opportunity.

Reckoning with this history requires more than acknowledgment. It requires commitment. Public policy must be reoriented toward equity and justice. Historical commissions must be empowered to investigate, document, and disseminate the full truth. Reparations—monetary, educational, and institutional—must be put on the agenda, not as charity, but as a matter of moral debt. Curricula in every school must tell the whole story, not just of slavery’s horrors, but of Black resilience and brilliance.

Archives must be opened. Land titles must be reexamined. Financial institutions that gained from slavery must fund scholarships, community development initiatives, and restorative economic programs. Churches that once baptized enslaved people while preaching obedience must atone through action. Universities must not only research their connections to slavery but rectify the imbalances that persist in access, faculty diversity, and wealth distribution.

Florida stands at a crossroads. It can choose to continue whitewashing its history, policing its memory, and ignoring the foundational truths of its existence. Or it can become a model for truth-telling and repair—a place where history is honored, justice pursued, and communities restored.

The enslaved Africans who labored in Florida’s fields, ports, and homes did not do so in vain. Their lives mattered. Their dreams, though crushed by chains, live on in every protest march, every community center, every child reciting “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” They built more than roads and cities—they built the moral foundation upon which the fight for justice continues.

Their story is Florida’s story. And until that story is fully told, the state will remain haunted not just by its past, but by the future it refuses to make right.

The struggle to confront and repair the damage of slavery in Florida continues to be waged by those most directly impacted by its legacy. This struggle is not abstract—it is practical, immediate, and driven by a need for survival as much as by a yearning for justice. From the descendants of the Rosewood massacre who fight for restitution and recognition, to the community activists in Liberty City and Eatonville working to preserve Black spaces from gentrification, to educators developing Afrocentric curricula in schools with limited funding, the effort to reverse the consequences of slavery is ongoing and personal.

It is also intergenerational. The legacy of slavery is not only evident in physical conditions or economic data—it resides in the cultural memory, the spiritual traditions, the culinary legacies, the naming practices, and the familial bonds of Florida’s Black population. Cultural continuity was one of the most potent acts of resistance under slavery, and it remains a defiant assertion of dignity today. The descendants of those once considered property carry with them an unbroken legacy of resilience, brilliance, and hope.

There is a spiritual dimension to this legacy that often goes unspoken in legal or academic discourses. The theft of centuries of labor, the violation of families, the suppression of human potential—these were not just crimes against law or society; they were violations of the soul. Florida's enslaved people built not only the economy but also its culture. They brought the rhythms of Africa into Southern Baptist choirs, they shaped cuisine that blended African, Caribbean, and Indigenous flavors, and they brought a cosmology that valued balance, reverence, and justice. The spiritual inheritance of Florida’s enslaved is a legacy of faith and moral clarity that continues to infuse the fight for justice today.

Despite this, the official reckoning with slavery in Florida has been halting and incomplete. In recent decades, token gestures have been made—commemorative plaques, museum exhibits, occasional acknowledgments by government officials. But these symbolic acts have not been matched by structural change. No comprehensive reparations package has been enacted. No official apology has come from the state legislature backed by tangible commitments. No system-wide audit of public lands, university endowments, or corporate assets has been conducted to determine the extent to which Florida's modern institutions were built on the gains of slavery. And until that kind of thorough, transparent, and sustained reckoning occurs, the stain of slavery will remain embedded in the fabric of the state.

One pathway forward lies in truth commissions—state-sanctioned, independent investigations that gather testimony, study historical records, and issue binding recommendations. These commissions could examine how slavery laid the foundation for current disparities in wealth, health, education, and incarceration. They could investigate which institutions gained financially from slavery and make proposals for restitution. Such commissions would not undo the past, but they would make it impossible to continue denying its implications.

Another pathway lies in land return and restitution. Much of Florida’s most valuable real estate was once worked by enslaved people. In some cases, Black families acquired land during Reconstruction, only to lose it through fraud, violence, or eminent domain. Identifying these cases and restoring land titles or compensating families for their loss is a concrete way to repair the harm inflicted over generations. Land was the basis of power in the plantation economy, and it remains the basis of wealth and opportunity today.

Additionally, targeted investment in Black communities—especially those with direct ties to historical sites of enslavement—must be prioritized. These investments should not be filtered through abstract “colorblind” programs but should explicitly acknowledge their purpose as reparative. This includes funding for Black-owned businesses, guaranteed access to housing, free tuition at state colleges and universities for descendants of enslaved Floridians, and the establishment of cultural centers, research institutes, and public art projects that preserve and celebrate Black history.

Florida’s public education system must also be overhauled to tell the truth—unapologetically, comprehensively, and frequently. Students of all races and backgrounds must be taught the truth about slavery’s role in shaping the state. This includes not only the brutality of the system, but also the courage of those who resisted, escaped, and fought for liberation. Schools should not shy away from naming the slave owners who built towns, funded universities, or served as political leaders. History must be rooted in the facts, not the myths of exceptionalism or innocence.

Finally, the spiritual healing that must occur cannot be imposed or rushed. It must come through mourning, memory, and meaning-making. Communities must have space and resources to honor the dead, to tell their stories, to rebuild what was lost. Healing is a collective process. It must involve not only the descendants of the enslaved but also the descendants of enslavers who are willing to face history with humility and courage. It must include those who have benefited from whiteness and are ready to dismantle the systems that uphold it.

Slavery in Florida was not a footnote. It was a defining structure of the state's formation and expansion. Its consequences are not distant echoes; they are present realities. From the earliest Spanish missions that enslaved Indigenous people, to the cotton and sugar plantations of the antebellum period, to the Jim Crow era of exclusion, to the redlined neighborhoods and underfunded schools of today, Florida has been shaped by slavery’s long shadow.

Yet within that shadow are the lights of resistance, the voices of survivors, the movements of dreamers, and the hope of liberation. The enslaved were never passive victims—they were architects of freedom. Their descendants carry that legacy forward, building not only resistance to injustice but also visions of a society rooted in equity, love, and truth.

To honor them requires more than words. It requires action—real, sustained, courageous action.

Only then can Florida claim to be free.

Only then can justice rise from the soil that was soaked with the sweat and blood of those who built it.

Only then can the full story of Florida be told.

And only then can the promises of liberty finally mean something real for those to whom it was long denied.

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

BlackWallStreet.org

Slave Records By State

See: Slave Records By State

Freedmen's Bureau Records

See: Freedmen's Bureau Online

American Slavery Records

See: American Slavery Records

American Slavery: Slave Narratives

See: Slave Narratives

American Slavery: Slave Owners

See: Slave Owners

American Slavery: Slave Records By County

See: Slave Records By County

American Slavery: Underground Railroad

See: American Slavery: Underground Railroad